Epilepsy 101

About 470,000 American children have epilepsy. Epilepsy doesn’t just have one presentation — it affects children at different ages and in different ways. For some, it will be a temporary problem, easily controlled with medication and outgrown after a few years. Others may need to manage it throughout their lifetime.

Whether your child has a new diagnosis of epilepsy or it has been a co-occurring diagnosis for years, we’ve gathered resources to help you support your child at school, at home, and in the community. For insights, we spoke to Elaine Wirrell, MD, a pediatric epileptologist and co-editor-in-chief of Epilepsy.com; William Gallentine, DO, pediatric epileptologist and interim chair of pediatric neurology at Stanford University; Audrey Vernick, director of patient and family advocacy for the Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery Alliance; and Leslie Lobel, Undivided’s Director of Health Plan Advocacy.

What are the signs and symptoms of epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder that causes recurring, unprovoked seizures. But what exactly is a seizure? Dr. Wirrell explains that a seizure is electrical activity in the brain that occurs when electrical currents misfire. Misfirings may manifest in various ways, each impacting a child differently. Some signs and symptoms may be quite obvious, and others may be more challenging to recognize. Seizures can occur at any age. There is no magic age at which a parent can say, “My child will never get epilepsy now.” However, epilepsy most commonly becomes evident by age 10.

Types of seizures

Seizures are classified into two groups: generalized seizures affect both sides of the brain and can have a physical component, such as a fall or muscle contraction (ex. jerks), or no physical component. Focal seizures (also called partial seizures) are located in just one area of the brain and can be divided based on whether consciousness is impaired during the event. Generalized and focal seizures are then further classified into seizures that have a physical component (motor) and those that do not have a physical component (nonmotor). Here are some of the different kinds of seizures and how you can spot them in your child. You can find more information on each of the seizure types listed below here.

Generalized seizures

Absence seizures (previously known as petit mal): absence seizures are generalized nonmotor seizures and two most common types are typical and atypical. These seizures can easily be mistaken for daydreaming. Your child may suddenly stop what they're doing and stare for 10 or 15 seconds and then go back to their normal activity. Unless you're trying to interact with your child during those 10 or 15 seconds, you might not recognize that they've had an absence seizure.

Tonic clonic seizure (previously known as grand mal): this type of generalized motor seizure is what most people picture when they think of seizures — shaking and rapid muscle contractions. If it happens, make sure your child is safe during the seizure, then proceed to the emergency room after the seizure has ended so that your child can have immediate evaluation and testing. Tonic-clonic seizures can also start in one side of the brain and then spread to affect both sides. When this happens it’s called a focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizure.

Focal seizures

- Focal aware seizures or focal impaired awareness seizures: during a focal seizure, your child may stare unresponsively, usually for a bit longer than for an absence seizure — perhaps for up to a couple of minutes. Afterwards, your child may appear confused. Unless you are interacting with your child during that time, it might be challenging to notice a focal seizure. They can be responsive during these seizures — respond to their name, and even speak. However, focal seizures can also involve repetitive movements like lip smacking, eye movements, or tapping a hand or finger. If your child is staring for a long period of time, watch for small, repetitive movements.

- Epileptic or infantile seizures: this kind of seizure involves brief (1-3 second) muscle flexion (arms and legs pull into the body) or extension. They are most common during infancy.

- Gelastic seizures: these seizures are often called laughing seizures — the person may look like they are smiling or smirking, accompanied by uncontrolled laughing or giggling.

- Focal nonmotor seizures: these seizures can cause changes in any one of the senses.

- Autonomic seizures, which impact the nervous system and involuntary functions, and may cause changes in heart rate, breathing, etc.

- Behavior arrest, in which movements stop all together.

- Emotional or cognitive seizures, which can impact how people think or feel, including changes in speech or memory, or sudden emotional change.

- Sensory seizures, which affect a person’s five senses, including experiencing smells, sounds, sensations, sights, that aren’t there.

Both generalized motor and focal motor seizures can also be classified as:

- Myoclonic seizures: these seizures cause a quick, uncontrollable muscle movement and can be easily mistaken for muscle twitches.

- Atonic seizures: “drop” seizures where the muscles in the body relax, consisting of sudden loss of muscle tone.

- Clonic seizures: repetitive jerking or twitching.

- Tonic seizures: the muscles in the body suddenly become stiff and rigid.

So what exactly happens during a seizure? Dr. Gallentine describes this more in this video.

A note on a rare condition called SUDEP

This is very rare, but parents should be aware of Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP). As Dr. Wirrell explains, “[SUDEP] is generally associated with convulsive seizures — not just the absences but the bigger seizures where you have generalized shaking/rhythmic shaking. If a seizure happens at night, most of the time children will recover from that fine, but very, very rarely that seizure can cause suppression of breathing and the person can actually pass as a result of the seizure during sleep. The way we try to minimize that risk is to control seizures better. But families need to be aware of that because that is going to impact their decisions for adjusting treatment, or maybe thinking about surgery if medicines aren't working.”

This may sound frightening, but know that the best way to prevent SUDEP is to do everything you can to lower your child’s risk of seizures — through medication, therapies, dietary changes, surgery, trigger avoidance, adequate sleep, etc.

Co-occurring conditions in children with epilepsy

Some children with epilepsy just have epilepsy. However, most of the time, children with epilepsy have other related conditions. One study cited by the Academy of American Pediatrics shows that around 80% of children with epilepsy “also have a cognitive impairment and/or at least one Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) disorder,” such as ADHD, learning disabilities, depression, anxiety, or autism.

As Dr. Wirrell notes, “[Co-occurring conditions] are very common in kids with epilepsy. Not everyone with epilepsy has that, but they are more common. Learning problems affect a fair minority of children with epilepsy. That's a concern. ADHD is much more common amongst children with epilepsy, particularly if epilepsy is not easily controlled with medication. Mood disorders, depression, anxiety are much more common. Autism is more common. Sleep problems are more common. So it really depends on the type of epilepsy you have and what the cause is. But we do see children with epilepsy often having more than just epilepsy.” Here is more information on co-occurring conditions in children with epilepsy:

- ADHD is the most common co-occurring disorder in children with epilepsy, with studies suggesting the presence of ADHD in around 30-35% of children with epilepsy (compared to 3–5% in the general population). This is particularly true if epilepsy is not easily controlled with medication.

- Autism is another common co-occurring disorder in children with epilepsy, with data showing ranges of around 20-25% of kids with autism having epilepsy (compared to 1–2% of the general population). Some studies suggest that epilepsy onset appears to occur during two age peaks in children with autism: infancy and adolescence, with autistic women more likely to have epilepsy than autistic men. While the connection between epilepsy and autism is still being studied, research has shown that there are shared neurological and genetic mechanisms that contribute to both.

- Sleep disorders and epilepsy are also closely related. Sleep can impact the “frequency, occurrence, timing, and length of seizures.” Children can also have nocturnal seizures that happen during sleep. This can look like “brief awakenings from sleep to dramatic movements of the arms and legs or even sleepwalking or making noises.” While nocturnal seizures can happen to anyone with epilepsy, they are often associated with a rare form of epilepsy called sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy, which “can look like a simple arousal from sleep, at times confused as a nightmare or night terror.” These seizures may last a few seconds to a few minutes but are usually about 30 seconds. While symptoms can overlap, here are a few ways a night terror is different from a nocturnal seizure: night terrors don’t often involve involuntary motor movements, are more common in the first half of sleep, and often involve some kind of daytime impairment.

- Depression can also co-occur with epilepsy, sometimes related to medication, severity of seizures, and learning how to cope with the challenges of epilepsy.

- Anxiety, similar to depression, can also accompany epilepsy, either as a reaction to the diagnosis, a symptom of the epilepsy, or a side effect of seizure medicines. It’s also important to note that people with high anxiety can experience panic attacks, which are sometimes misdiagnosed as epilepsy (or vice versa). But there are differences. A description of the symptoms can help differentiate between the two. For example, panic attacks usually last longer than seizures. During a panic attack, a person is also aware of their feelings and their surroundings. Another difference is that during a seizure, people often perform repetitive and uncontrolled movements that don’t occur during panic attacks. Because the two can be similar, tests such as an EEG or MRI can help to differentiate between the two.

- Genetic conditions also play a role in epilepsy. This happens “when an individual inherits a gene or a number of genes that result in a higher likelihood of seizures.” It’s believed that around 30–40% of epilepsy cases have a genetic cause. Some genetic conditions that include epilepsy as a symptom are Fragile X syndrome, Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF-1), and Rett syndrome. If your child has epilepsy, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends genetic testing in certain circumstances — for example, if the epilepsy started before the age of two years.

Many families are understandably frustrated when doctors can’t find a cause for the epilepsy. It’s scary not knowing, and it can feel like if you don’t know the “why,” you can’t find the right solution. However, it could be the best answer because, as Dr. Wirrell tells us, if doctors can’t find a cause, the likelihood of outgrowing epilepsy is much higher than if doctors do find a cause. However, if the child has a co-occurring neurological diagnosis, like cerebral palsy or intellectual disability, then they have a lower likelihood of outgrowing their epilepsy.

It is also important to treat not just the seizures but the whole child. Dr. Gallentine explains that neurologists not only look at seizures but also assess your child’s learning capacity and development. Neuropsych testing, for example, is a useful tool that helps doctors screen for other things beyond seizures. It is important that all professionals work together, so your child’s medical team should work with your family and your child’s school. For example, if a child is “staring off,” school professionals may think they have poor concentration and focus. This may lead to a diagnosis of ADHD and treatment with medication (which you might find isn’t improving your child’s concentration).

With some neurological testing, you might discover that your child has absence seizures, not ADHD. (Note: this doesn’t mean your child can’t have both ADHD and absence seizures.) It is important to look at all of your child’s development; a neurology team can help with this process.

Specialists who diagnose and treat epilepsy

If you think your child is having a seizure, you will need to see a pediatric neurologist, and preferably a pediatric epileptologist. While epileptologists and neurologists are similar, there is one main difference. A pediatric neurologist treats brain and neurological disorders in pediatric (ages 18 and under) patients. An epileptologist is also a neurologist, but they have subspecialty training in seizures and epilepsy in children. Their expertise is specifically in “seizures and seizure disorders, as well as anticonvulsants and advanced treatment options such as epilepsy surgery.”

Because there are fewer pediatric epileptologists, it will likely be quicker to get your child an evaluation with a pediatric neurologist. For kids who need more specialized care, it may be necessary to see a pediatric epileptologist, who can fine-tune a treatment and help make decisions about whether a surgical intervention could help, especially if there are no changes in seizures after three months of treatment or medication.

But what if there is a long waitlist to see a doctor? If you are unable to make an appointment with a specialist, your pediatrician can also order an EEG. If seizure activity is evident, this will alert the neurology team that your child needs to be seen as soon as possible. Also, if you believe your child is having frequent seizures, especially tonic clonic seizures, you can go to the emergency room to obtain testing and, if needed, be connected with the neurology team sooner. Other specialists you may see include epilepsy nurse practitioners, epilepsy neurosurgeons, EEG technicians, clinical neuropsychologists, neuroradiologists, neuroscience nurses, and more.

Video evidence is also important for an epilepsy diagnosis, especially if you’re waiting to see a neurologist. If you think your child is having a seizure, Dr. Wirrell suggests recording the event. Dr. Wirrell discusses the importance of video evidence:

How and when epilepsy is diagnosed

An epilepsy diagnosis includes gathering and putting together information from you, your care team, and your child’s test results. A doctor will make an epilepsy diagnosis based on evaluation of your child’s medical history, physical signs and symptoms, and the results of tests such as neurological exams and an EEG.

In this clip, Dr. Gallentine explains how an epilepsy diagnosis is made:

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

An EEG is an important part of getting an epilepsy diagnosis. Even with video evidence, a pediatric neurologist or epileptologist cannot make a diagnosis unless your child has an EEG, a medical test used to measure electrical activity in the brain. To obtain an EEG, a number of electrodes are applied to your child’s head with spaghetti-like wires to monitor the electrical brain activity. It will not hurt your child, but it may be uncomfortable. An EEG may take a few hours or up to three days in the hospital so that the proper data can be collected. You can also have EEGs done at home.

As Dr. Gallentine explains, “During your outpatient, we have eight-hour studies that we could potentially do. And then we also have 24-hour ones that can be done either in the hospital, or you can wear an EEG and take it home. And sometimes, the ones that you take home can last anywhere from 24 all the way up to 72 hours.” But whether at home or at the hospital, EEGs can take as long as three days, depending on what they’re trying to capture. For home EEGs, Dr. Wirrell tells parents to make sure to wash the child’s hair before the study as they can’t bathe or shower with the leads on. Also, because the EEG will be recorded on video, try to keep your child on camera.

How do you know which study is right for your child? Dr. Gallentine tells us that it depends on what you’re trying to accomplish and capture with the EEG: “If we're trying to capture a spell and the spell is occurring five times an hour, I can capture it in a shorter EEG. If it's occurring once a day, sometimes we'll try to do an eight-hour EEG. But sometimes, that's where a 24-hour EEG comes in. And so, if they're less frequent than that, then you space it out and do a longer study. Sometimes we're just looking to do 24 hours, get a good sleep sample — that will give us all the information that we need.”

What to expect during the EEG

As the parent or caregiver, you will be given a button to push during the EEG if you see any suspected seizures. Then, the professionals reviewing the results will make sure to look closer at those episodes. The write-up report will include whether they were actually seizures.

When you receive your EEG results will depend on the hospital or center you are at, and they may be delivered virtually or in person. There’s also a possibility that the hospital staff will ask you to stay longer because the EEG didn't capture anything.

How to support your child before and during the EEG

For a child, it can be very scary to have wires glued to your head. Dr. Gallentine tells us that EEGs are very dependent on the child and whether they can tolerate it for 24 hours. For example, if you put the leads on, will the child yank them off? Can they actually go home with the wires and keep them on for 24 hours?

He explains, “Fortunately, we've gotten pretty good about being able to wrap the kids' heads up so they can't really get into it very easily, and we're pretty successful in most circumstances of keeping the kids on there. But there are certainly some kids, particularly those who have an underlying intellectual disability or autism, that don't really understand why these things are on their head. And oftentimes, they will be trying to remove them and things of that nature. And so, if that happens, it's fine. We do the best we can to try to gather as much information as we can, and just realize that that's kind of a shortcoming of the events. But every little bit of information is helpful, and so we definitely go through the exercise of trying to do it even if it might be a little bit more of a challenge.”

That’s where priming comes in. If your child has sensory issues, it can be especially challenging, so it is important to discuss what will happen before the test. For example, telling your child, “Some sticky, goopy gel will be put on your head to help keep the stickers in place, which have some rainbow colored wires attached to them. Then you'll have something like a ‘funny hat’ put on your head.” You may want to create a Social Story or show a YouTube video like this one from Boston Children’s Hospital to prime your child as much as possible so that they know what will happen before you even enter the hospital. Also, your child may benefit from acting the procedure out with a doll. The “unknown” can cause a child anxiety, whereas knowing exactly what will happen can help ease fears for some children.

Also, do not hesitate to contact the hospital child life specialist or request a visit from a therapy dog if you think it may help your child.

During the few hours or even days for the EEG, it is important that your child is comfortable and has fun things to do as distractions. Here are some tips for what to bring, knowing every child has their unique, loved items:

- Comfortable clothes

- Favorite dolls/action figures for comfort and play

- Board games

- Coloring books/creative activities that don’t require many materials

- Books for your child to read independently and for you to read to your child

- Homework, if your child has any

- Favorite snacks

- Electronic devices (ask medical professionals to make sure they will not interfere with the testing)

- New toys or games your child hasn’t seen before

- A favorite blanket or stuffy for comfort

- Pillows and bedding to make the hospital more comfortable, especially if you will be sleeping on a couch/bed in your child’s room

You can also ask family members to call or FaceTime, so your child knows that everyone cares and is cheering them on throughout the testing.

What do you do if the EEG is negative?

Sometimes you go through all the testing only to discover that no seizure activity was found, which can be frustrating. “EEG is not a perfect test,” states Dr. Wirrell. “We do have some patients who have epilepsy and who have completely normal EEG repetitively.” This is why it is important to have a video history, which can inform the medical team. And the reverse can be true as well: sometimes something that’s not a seizure can look like a seizure to a nonmedical person. If you believe you have observed seizure activity, Dr. Wirrell suggests discussing with your provider whether the EEG should be repeated. Many parents report that their child had to undergo several EEGs before they caught seizure activity.

Dr. Gallentine agrees that the EEG should be repeated. In this video, he explains why it is important not to just repeat the same EEG again, but to do a longer duration and at different times in the day, so the EEG has a higher chance of capturing seizure activity.

Dr. Gallentine discusses why EEGs may need to be repeated and recorded for longer durations:

The length of the EEG really depends on what doctors are trying to capture. If your child has more frequent spells, the doctors may be able to sample more quickly. Most importantly, it has to fit the child. How long will your child be able to tolerate the EEG? Will your child try to remove the wires? Will your child be more comfortable in the hospital or at home? Doctors are always trying to balance the best way to obtain the best sample, especially when kids are very young.

How you can avoid surprise medical bills for the EEG

It is stressful enough to care for your child while seeking a diagnosis. The last thing you need is to receive the surprise of a huge bill. Leslie Lobel, Undivided Director of Health Care Advocacy, explains that EEGs are a covered benefit under imaging on most if not all health plans. However, EEGs may require a pre-authorization. If you are working with a network contracted facility, the provider will obtain the authorization (if needed) and collect the copay and/or deductible from you for your child's imaging. And for home EEGs, you will need to work with your insurance plan to ensure they cover it; not all do.

Lobel has the following tips for parents:

- If you are working outpatient with a major medical center, such as a children's hospital, they may accept Medi-Cal as secondary insurance. Be sure to ask if Medi-Cal can be billed the balance.

- If an initial request for authorization of imaging is denied, contact the imaging center. They will be able to instruct you how to handle an appeal with your health plan.

- Do not accept the first denial as the final decision. Many times, health plans just need more information, and once the information is submitted, the EEG is approved.

How to help your child manage seizures

An epilepsy diagnosis will affect your child, but it doesn’t have to limit them. Your reaction will greatly influence your child’s acceptance of their diagnosis. It is important that your child understands they did nothing wrong. As an adult, you know that they can’t control having epilepsy any more than they can control whether they have blue or brown eyes. However, children haven’t always developed that perspective — but they will, when you model it for them. The important thing for you and your child is to learn how to manage the seizures.

Avoid triggers

One of the best ways to manage seizures is to try to avoid triggers. Triggers will depend on the type of seizures; however, in general, lack of sleep, stress, and anxiety can all trigger seizures. For example, anxiety can cause lack of sleep, which then can trigger a seizure, so, it is especially important that children with epilepsy learn techniques for stress management. Other seizures can be triggered by things like flashing lights or certain sounds.

A child may get a warning prior to a seizure. They might get a little nauseated or get a bad feeling, get a bad taste in their mouth, or even notice a bad smell. If this happens, encourage your child to get to a safe place and tell an adult (preferably an adult who is aware and educated about their condition).

✅ Tip: you may want to get your child medical alert bracelet. These bracelets can give valuable information when your child can’t speak and you are not present. If it is known your child has epilepsy, then medical professionals will know how to proceed if an emergency occurs. These bracelets and necklaces come in a variety of price ranges and can be purchased from the MedicAlert Foundation or other companies. Insurance or health savings accounts (HSAs) may cover these bracelets. You might need to ask your specialist or your pediatrician for a prescription.

You may also consider seizure alert dogs who are trained to respond to a seizure in someone who has epilepsy. Seizure dogs can alert families when a child has a seizure, lie next to someone having a seizure to prevent injury, activate a device that rings an alarm during a seizure, and more. Read more about service dogs and find a list of service dog agencies in our article here.

Dietary therapy

Dietary therapy is another approach to help control seizures. If medications are not effective, some doctors prescribe the ketogenic diet, which is a special high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet that helps to control seizures in some people with epilepsy. This is a treatment plan supervised by medical staff. Usually, the body uses carbohydrates for its fuel, but because the ketogenic diet is low in carbohydrates, fats become the primary fuel. While people often talk about doing a “keto” diet for weight loss, a true ketogenic diet is carefully monitored by a dietitian. It requires precise measurements of calories, fluids, and proteins, and all food is weighed and measured. If this sounds challenging, it is, but it has been effective for some individuals with epilepsy.

Managing seizures with medication

Seizures can often be controlled with medication, but there are many different kinds. The first one your child tries may not be effective, and/or it may have side effects, so your child might have to try more than one.

As Dr. Gallentine tells us, there is no perfect anti-seizure medication — they all have some potential side effects. “The reality of it is, though, in most circumstances, we can find a seizure medication that works well for most individuals and we're able to get them to tolerate that medication without side effects. It's important as you're talking about the options with your doctors, side effects and the possibility of various side effects are discussed with each of those medications because they all have their own pros and cons. And it's those potential side effects, in combination with the types of seizures that a child may be having, that weigh into our decision making in terms of which options we would offer.”

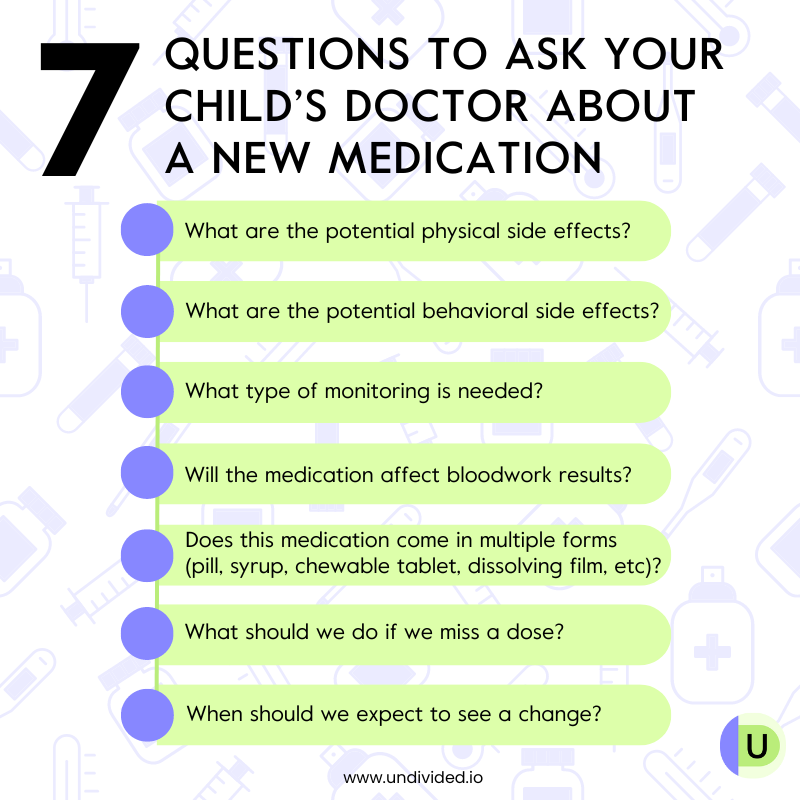

When working with a doctor to select a medication, Dr. Wirrell and Dr. Gallentine have suggestions for parents:

- Have a clear sense of the potential side effects and what you need to watch for. For example, Dr. Wirrell tells us that some seizure medications can be associated with rashes, and those rashes can become very severe very quickly.

- Ask the doctor what type of monitoring is needed for the anti-seizure medication.

- Know when bloodwork should be taken. The timing of the bloodwork (i.e., before or after medication) could affect the reading in the same way blood sugar varies for a person with diabetes based on when they’ve eaten.

- Take into account the formulation of medication, Dr. Gallentine tells us. “How does it actually come in terms of pills, syrup, dissolving films, tablets, or chewable tablets? There are multiple different ways these preparations come, and you can take that into consideration as well.”

- If you miss a dose, Dr. Wirrell says, “Nobody's perfect and eventually you will miss a dose. In that situation, we tell the families to make up the dose as quickly as possible.”

- In addition, it is important to know when you should see a change. Dr. Wirrell explains, “Oftentimes, we start medicines at a low dose and we gradually increase until we get to the target dose. And families need to understand when they can expect this medicine to really work and at what point, if you see a seizure, do you call your doctor and say, ‘I don't think this medicine is working.’ Ask the doctor when you should be able to tell if the medicine is working.”

- Take into account co-occurring conditions and current behaviors. For example, if your child is already prone to aggression, Dr. Gallentine tells us that putting them on a medication that also has aggression as a side effect may not be a great option. Instead, try something that has a positive behavioral effect.

- Medication may change as your child gets older. Dr. Gallentine tells us, “There are a subset of kids that can all of a sudden lose seizure control. Hormones may play a role in some of that, specifically for our female population. And so, in that circumstance, oftentimes switching to a different seizure medication might be the best option.”

If you find that two or more medicines have failed to control seizures, Dr. Wirrell tells parents to have their child seen at a comprehensive epilepsy center to find out why the seizures are not controlled and what other treatment options might be appropriate, such as surgery, change in diet, etc.

Epilepsy medications can be covered by your insurance. Depending on the medication and its tier within the plan's coverage, it may be dispensed at your local pharmacy or it may come via mail order from a specialty pharmacy provider.

✅ Tip: if the prescription is denied, do not accept this as a final decision. Your doctor may need to provide additional information in order for the pharmacy to approve to fill the prescription.

Managing seizures with surgery

According to the Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery Alliance, “Surgery for epilepsy is when the surgeon removes, disconnects, ablates, or stimulates a part of the brain to stop or slow down seizures.” About 30% of people with epilepsy have what is known as drug-resistant epilepsy, which means no medication or diet will stop their seizures.

Drug resistance is determined once a patient has failed to achieve seizure freedom after trying two appropriate and tolerated anti-seizure medications. These patients should be referred to an experienced epilepsy center to see if they are candidates for one of the many surgeries that may stop or slow down their seizures.

Unfortunately, families often end up trying multiple medications before a neurologist will suggest surgery, or refer the family for a neurosurgical consultation to learn more about their options, Vernick explains. “After failure of two anti-seizure medications, it’s time to start the conversation about epilepsy surgery,” she says. “Timely referral to an epilepsy surgery evaluation allows parents to exercise their right to make an informed treatment decision for the child.”

Vernick explains more here:

Vernick says it's important to have a knowledgeable doctor who has seen a lot of cases like your child’s. It is also important that this doctor is part of an experienced team. It is not just your child’s doctor deciding what to do, but an entire team of informed doctors who decide whether this is the right surgery for your child.

The idea of brain surgery is understandably shocking and scary for many families. It is important to ask questions and get a second and even a third opinion. Vernick says, “A lot of families have this idea that epilepsy surgery is really dangerous… However, the reality is the risk of death or serious impact from surgery is less than a half a percent.”

The Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery Alliance has a list of questions to ask your doctor and the hospital to help you make a decision. Also, a parent support navigator, who has traveled this journey with their child and received training, can assist.

Vernick suggests recording your conversations with the neurosurgeon. It is hard to understand everything the first time you hear it, and “this way, you can go back and reflect on it. Nobody’s going to ask you to make the decision right in the moment.”

If your child isn’t responding to at least two medications, you can say start a conversation with their neurologist about surgery. Vernick tells us, “Sometimes we're worried about the impact on our child if we do surgery, but we have to also think about the potential impacts if we don't. Referring a child for an epilepsy surgery evaluation doesn’t mean anyone has decided a child will have epilepsy surgery. It means all treatment options will be reviewed so that parents can make informed healthcare decisions for their child. It gives you the opportunity to find out more about your options.”

She adds that pre-surgical testing might also uncover other aspects of your child’s epilepsy that you didn't know about, such as an underlying condition or other treatment options that aren't even surgical. “So that's really important to remember: the referral to surgery is a chance to have that conversation and have all available tools in the toolbox to help your child.”

Vernick describes these surgical options; you can ask your doctor if any of these might be possible for your child:

- Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy (LITT), or laser ablation surgery, is a minimally invasive procedure that uses a laser (light and heat) to destroy a small part of the brain that causes seizures.

- Neuromodulation devices act directly on the brain by delivering electrical impulses to a targeted area, similar to how a heart pacemaker works. These are special devices implanted in the skull, neck, or chest. The device stimulates the brain with very low electrical currents. Many epilepsy centers are implanting devices called VNS (vagus nerve stimulation), RNS (responsive neurostimulation), or DBS (deep brain stimulation) devices.

- Lesionectomy works by removing a lesion (a damaged or abnormally functioning part of the brain). Some people have an area of stroke or tumor or an epileptogenic zone, meaning a region of the brain where seizures are starting generally surrounding a lesion.

- Lobectomy (removal of a lobe of the brain), or lobe resection, is done when the lesion is too big for a lesionectomy, and the whole lobe needs to be removed. A lobectomy can be temporal (the most common), occipital, parietal, or frontal.

- Hemispheric surgeries disconnect one half of the brain from the other to make sure that the damaged hemisphere doesn't send epileptic activity to the undamaged side. This is considered a functional hemispherectomy or a hemispherotomy. An anatomical hemispherectomy is when all four lobes of one hemisphere of the cerebral cortex are removed in their entirety.

There are other surgeries that can be considered as well. If you are thinking about surgery, the Pediatric Epilepsy Surgery Alliance shares a few things to consider when making the decision.

Surgery success

“All patients who are drug resistant are epilepsy surgery candidates, and epilepsy surgery could eliminate their seizures completely in some cases, reduce the seizures significantly, and improve quality of life in many cases,” Vernick says.

Vernick shares her son’s story: “My son had surgery when he was two. He was having 200 to 300 seizures a day. He was losing skills and function. We had to do it. We did not have a choice. And he's been seizure-free for 18.5 years, and he's in college now. That would not have happened if he had continued to have seizures.” For other patients, surgery may not eliminate seizures but may make them less frequent and improve their overall quality of life. After all, that is the goal: to live the best life possible.

The cost of surgery

As Vernick tells us, “I have never heard of a patient being denied epilepsy surgery when it was needed unless it is for a new or experimental treatment.” She explains that typically, the hospital will work with your insurance company to get surgery covered. For other costs, such as a long hospital stay, pre-surgical testing, the surgery itself, rehabilitation afterwards, etc., Vernick explains that the Neurology Social Services Network and nonprofit organizations can help match your family with local resources in your community for things like food, rent, and utilities expenses, or other things that you might need during and after surgery.

✅ Tip: Vernick’s organization will help parents find a surgical team and has a scholarship that will pay $1,000 in travel expenses associated with an epilepsy surgery consultation more than 50 miles from the child’s home.

Create a seizure action plan

The reality is that no matter how prepared you are in terms of seizure treatments, seizures may still happen now and then. It’s important that you have an action plan whether it happens at home, on a plane, or in a movie theater.

Make sure to let all caregivers know that your child has seizures so they know what to do if your child has one. Also, you’ll need any rescue medication close by. You or the caregiver should time the seizure, and if it is longer than five minutes, you’ll need to administer rescue medication.

How to keep your child safe during a seizure

If your child has a seizure, it is important to remember the 3 S’s: STAY, SAFE, SIDE.

- STAY: Stay with your child until they are fully awake. Also, remain calm. Your child will be more anxious and panicked if you are.

- SAFE: Make sure your child is safe and the area is clear of items that could cause injury.

- SIDE: Turn your child on their side. Also, make sure nothing is in their mouth and nothing is tight around their neck.

Dr. Gallentine explains this more:

The Epilepsy Foundation has more information on seizure first aid, including the 3 S’s, so check out their resources here. They offer virtual seizure recognition and first aid certification as well as a seizure first aid ready course. For sample seizure plans, check out this one from the Epilepsy Foundation.

Up next, read our article about supporting a child with epilepsy at home, at school, and in the community.

Author