Conservatorships (Limited and Full) in California

Coming to terms with our children growing up can be bittersweet - maybe even a bit terrifying- for parents, especially when our young adults are approaching the age of eighteen. As much as we may want to always protect and care for our kids, once they reach the age of eighteen, they are legally adults, faced with adult responsibilities and decisions. This milestone often brings plenty of questions for many parents of kids with disabilities. What happens when your young adult reaches eighteen and isn’t ready to make adult decisions? What are your options to protect them — financially, socially, medically, and otherwise — in making life decisions, independently and as a team? Parents may even find themselves faced with the question, “Is pursuing a conservatorship the right thing to do for my child, and if so, how does it work and where do I begin?”

To learn more, we reached out to Suzanne Bennett Francisco, President and CEO of Exceptional Rights Advocacy and Co-Director of the Supported Decision-Making California Advocacy Project (SDM CAP) for Disability Voices United, as well as Lisa MacCarley, attorney and founder of Betty’s Hope.

3 key takeaways

- A limited or full conservatorship gives someone else the legal right to make certain decisions on behalf of an adult who cannot care for themselves.

- Seeking conservatorship is a long and complicated legal process. The adult with disabilities (conservatee) will need their own lawyer.

- Families should carefully consider the risks and benefits before pursuing limited or full conservatorship. The goal is to help adults with disabilities retain as many rights and as much independence as possible.

What is a conservatorship?

According to the California Courts, "a conservatorship is a court case where a judge appoints a responsible person or organization (called the ‘conservator’) to care for another adult (called the ‘conservatee’) who cannot care for themselves or manage their own finances. A person cannot be placed under a conservatorship unless they are deemed to ‘lack capacity’ in some way by the court."

If a petition for conservatorship is granted, the court will appoint a conservator (also called a guardian in some states), who will make decisions on behalf of the conservatee.

There are two subtypes of conservators:

- a conservator over the person, who will make decisions regarding the individual’s personal needs, including their relationships, medical care, or education; and

- a conservator over the estate, who will handle financial matters like paying bills or managing a budget.

Note that being appointed conservator of the person does NOT automatically make that person a conservator of the estate. If it is determined that an individual needs a conservator of both personal and estate decisions, they will need to have someone appointed for each type, or as both.

A limited conservatorship is set up to support the needs of adults with developmental disabilities who are unable to provide for some, or all, of their personal or financial management needs. The disability must have originated before their eighteenth birthday, be expected to continue indefinitely, and constitute a substantial impairment. The conservator is responsible for encouraging maximum self-reliance while also ensuring the safety and well-being of the person.

A general (or “full”) conservatorship is set up for adults who cannot provide for their personal needs in terms of physical health, food, clothing, shelter, or finances, and who have lost the ability to make decisions. This can include:

- Aging adults

- Adults who have a major neurocognitive disorder (decreased cognitive function and loss of ability to do daily tasks) due to, for example, traumatic brain injury, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular disease, substance/medication use, severe developmental disability, or another medical condition

- Adults who have been severely injured (e.g. from a car accident)

For young adults with developmental disabilities, the idea behind adopting a limited conservatorship is to support the individual in gaining more independence. According to Mark Woodsmall, attorney and founder of Woodsmall Law Group, limited conservatorships don’t need to last forever, and should be set up while “having an eye for limited power.” The conservatee should retain as many rights as possible; ultimately, the goal should be to end the conservatorship for a less restrictive option, if possible.

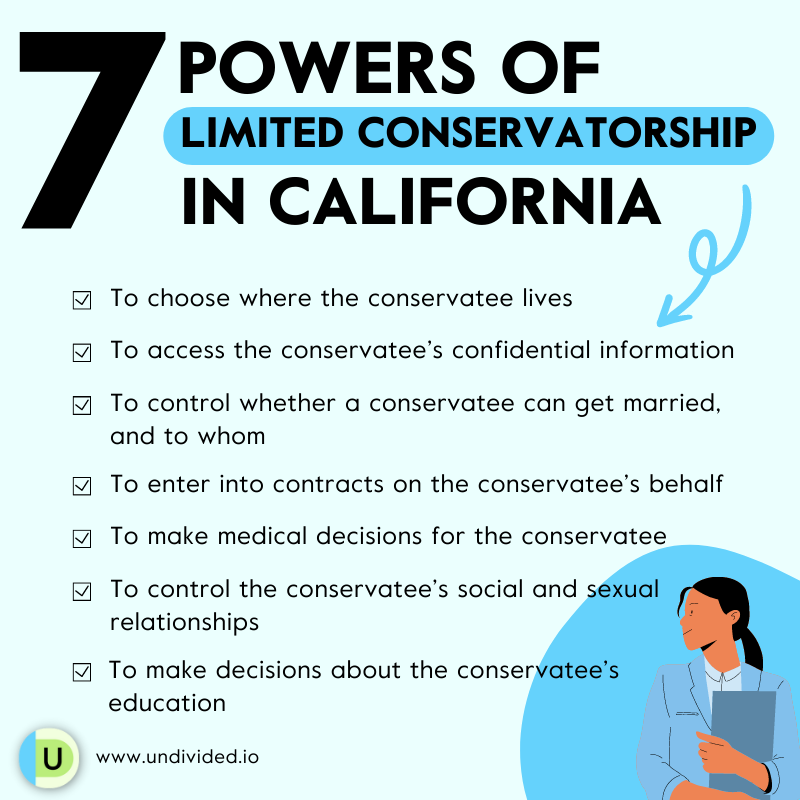

What decisions can conservators make on behalf of conservatees?

There are seven “powers” discussed in conservatorship cases:

In a limited conservatorship, the conservatee should retain any of the powers they have the capacity to exercise to promote as much independence as possible. The powers can also be shared between them and the conservator, to make decisions together. The conservator may be granted one or all of the powers (this can be later modified), depending on the abilities of the conservatee, but they are expected to help the conservatee develop their independence. In a full conservatorship, the conservatee does not retain any of the seven powers, giving the conservator complete control over all aspects of their life. In addition, a full conservatorship is usually intended to be permanent. (More on this below.)

A note on powers: For people with disabilities, a limited conservatorship can still cover all seven powers, but that doesn’t make it a full conservatorship. Sometimes, the court will grant a conservator all seven powers in a limited conservatorship, even if the application was for four or five, but the intention is still to give the conservatee as much autonomy as possible. In a full conservatorship, no autonomy is expected.

How is a conservatorship put into place?

To place a person under a conservatorship, a petition needs to be filed with the court, and all the appropriate forms need to be completed, including a notice of hearing and letters of conservatorship. The petitioner should show that alternatives such as supported decision-making have been considered.

Once the petition is filed, the potential conservatee must be given notice that they may be placed under a conservatorship. They have a right to go to court, object to the conservatorship as a whole, or in part, and hire their own attorney. They will be interviewed by a court investigator to ensure that a conservatorship is necessary. Then, the court will schedule a hearing.

During the court hearing, the court will inquire into nature and extent of the general intellectual functioning of the individual; evaluate the extent of the impairment of his or her adaptive behavior; ascertain his or her capacity to care for himself or herself and his or her property; and inquire into the qualifications, abilities, and capabilities of the person seeking appointment as limited or general conservator.

Establishing a conservatorship can be a long and overwhelming process, and consulting a lawyer can be helpful in navigating the ins and outs. The potential conservatee should have their own lawyer to advocate for their best interests, help them understand the proceedings, contribute information concerning their wants and needs, and make objections wherever necessary. If a family or young adult is unable to afford a lawyer to represent them, the court will appoint one.

For example, a conservatee may feel that they need help making medical decisions but are confident in their ability to make friends and maintain a meaningful social life.

MacCarley suggests providing the court with as much information about your young adult as possible, including reports from their Regional Center, teachers, and therapists. She stresses that not all attorneys and judges involved in conservatorship cases are fully knowledgeable about people with disabilities, and helping them get to know an individual, their abilities, and their capacities can be essential to the decision-making process.

It’s also important to note that the role of conservator can be granted to anyone over the age of eighteen, and may not necessarily be a parent. While family members can ask the court to be appointed as conservator, the court is the one who chooses. The court will conduct a criminal and financial background check on any proposed conservator, and the judge will have ultimate authority over who is appointed; they can also choose a professional to take the position, usually an attorney. In California, among conserved adult Regional Center clients (almost 50,000 people), half of them have a conservator who is not a family member. This can happen for many reasons; for example, if the parent who is the conservator dies, there isn’t always a clear path to who will take over as conservator next. In some cases, even if the parent has set up directions requesting that a sibling take over, the court isn’t required to honor their wishes.

Benefits of limited conservatorship

Limited conservatorships can be beneficial in protecting and supporting your young adult in the areas of their lives where there is a need, while also giving them independence and control whenever possible. For example, a limited conservatorship can be helpful for individuals who need medical care but are unable to process or understand medical terminology or who are unable to communicate independently with their doctors.

MacCarley tells us, “The goal is to give the young adult as much freedom as possible, to give them the greatest opportunity to live their most normal, natural lives.”

When it comes to establishing a limited conservatorship for young people who are not able to make sound decisions in all areas of their lives, the ultimate goal, as MacCarley puts it, should be that they find “as much independence and the ability to self-actualize as possible over the course of their lifetime.”

In a limited conservatorship, the judge will only give the conservator power to do things the conservatee can’t do without help. This may include:

- Deciding where the conservatee will live

- Looking at the conservatee’s confidential records and papers

- Signing contracts for the conservatee

- Giving or withholding consent for most medical treatments for the conservatee

- Making decisions about the conservatee’s educational and vocational training

- Giving or withholding consent to the conservatee’s marriage or domestic partnership

- Controlling the conservatee’s social and sexual contacts and relationships

- Managing the conservatee’s financial affairs (for a limited conservator of the estate)

The limited conservator also has a duty to help the conservatee develop self-reliance and independence, which includes providing support services, education, medical, and other services.

Special education attorney Grace Clark tells us, “A unique aspect of limited conservatorships is that they recognize that developmentally disabled adults may be developing at a slower rate than their nondisabled peers; they may not be ready to manage their finances and school decisions at age eighteen but may be able to do so at age twenty-five.” She adds that a limited conservatorship is reviewed the first year after it is granted and then every two years to ensure that the conservatee retains as many rights as possible.

Woodsmall adds that the conservatee should have an active voice throughout the process and have as few rights removed as possible; ultimately, the goal should be to end the conservatorship for a less restrictive option, if possible. When the conservatee is ready for their conservatorship to be terminated, supported decision-making agreements can be created to show the court how the young adult can be successfully supported.

Risks of limited conservatorship

Francisco tells us that sometimes conservatorships are limited only in name, such as in the case of Marie Bergum. A person may have all of their decision-making powers stripped from them without being put into a full conservatorship.

Potential risks of a limited conservatorship include:

- A conservatee has some of their rights taken away, and the decision-making in those areas will be the responsibility of another person, which can sometimes result in a conservatee’s wishes not being taken into account.

- Some conservatorships are contested and can look similar to custody battles, resulting in expensive court cases. The conservator takes their fees from the conservatee’s estate, even legal fees to defend their conservatorship.

- Once court oversight is instituted, it can be difficult and complicated to remove it.

- The court may appoint someone else, such as a public guardian, as conservator instead of the parent.

According to Linda Kincaid, MPH and co-founder of Coalition of Elder and Disability Rights (CEDAR), there have been cases where a Regional Center has successfully petitioned the court to replace a parent as conservator with a public guardian. There have even been a few cases where family members have been restricted or even prevented from visiting their adult family members. The conservatee or their family may also be required to pay the guardian’s fees. Kincaid also cautioned that conservatees do not always have access to the court to advocate for themselves.

Something else to consider is travel. A conservatee who wants to go on a vacation or take a trip out of state or the country may need court authorization. And if the conservatee is being moved out of state, the conservator will need permission of the court prior to moving. The court-appointed conservator must always consult the court to determine if the move is in the best interest of the conservatee.

When is a limited conservatorship inappropriate?

Benefits and risks of full conservatorship

Limited and full conservatorships share many of the same risks and benefits. Under a limited conservatorship, the conservator is in charge of defining the limits, so the system is open to harm and exploitation in situations where the court appoints a conservator. If the conservatee lacks capacity in all areas, a full conservatorship may be beneficial by allowing the conservator to care for them and act in their stead in important matters. However, this also puts a conservatee at risk of their wants and needs being unheard, or of being taken advantage of by a conservator who isn’t taking their whole self and best interests into account.

A general or full conservatorship is put into place for individuals who need high amounts of support in all areas of their lives. In a full conservatorship, the conservator has complete control over all aspects of the conservatee’s life. Conservatees in full conservatorships are not expected to gain new skills or become more independent over time, so a full conservatorship is often permanent.

When are full conservatorships inappropriate?

If a conservatee has the capacity to make independent decisions in any area, then a full conservatorship is likely not appropriate. For example, if an individual needs support with their medical care, but expresses preferences when it comes to where they live or who they socialize with, then a limited conservatorship or another less restrictive option may be a better fit.

Conservatorships may also be inappropriate when a person’s capacity is being contested. According to Woodsmall, “When a person has capacity, the person seeking a conservatorship might not have the best intentions.” For example, if the potential conservator is petitioning the court to gain control over a person’s assets when that person can make sound financial decisions, the potential conservator may be interested in their own gain. He also says that the court investigator, Regional Center, and loved ones can help a court decide if their young adult really needs a conservatorship.

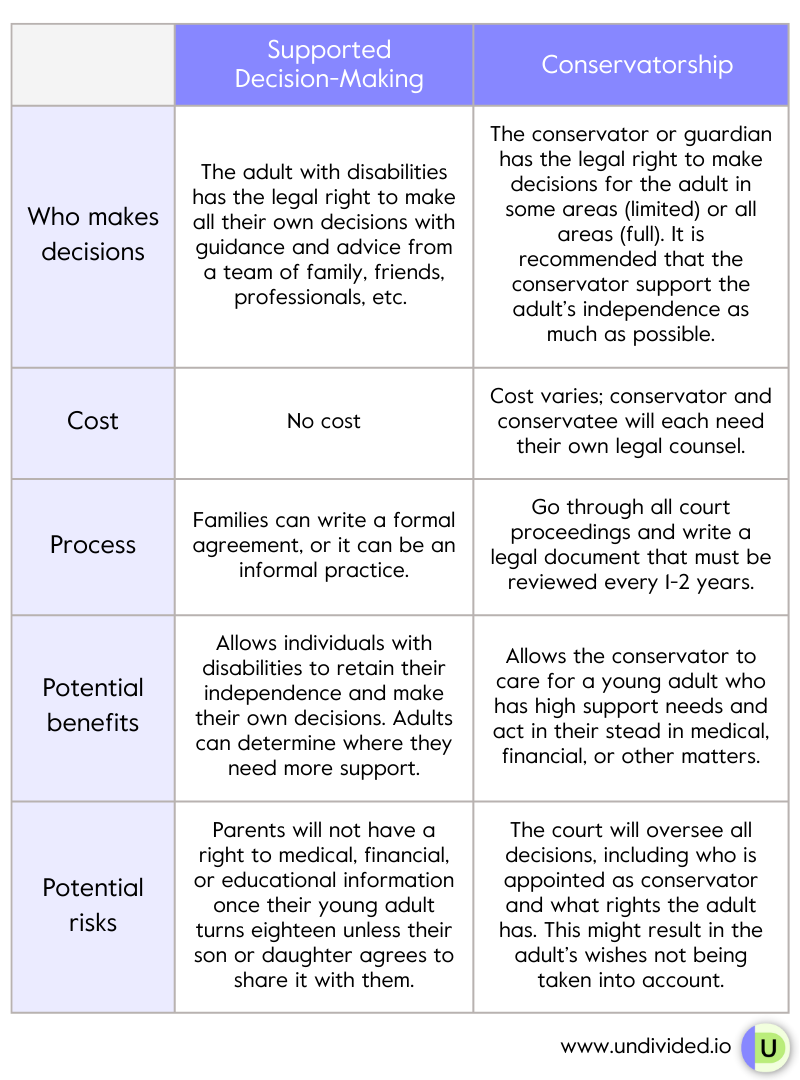

Before a conservatorship can be put into place, the law requires that alternatives such as durable power of attorney or supported decision-making be considered. The National Guardianship Association recommends families try supported decision-making before petitioning for a conservatorship.

Explore alternatives to conservatorship

How conservatorships are changing

Assembly Bill 1194

In September 2021, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 1194, otherwise known as the #FreeBritney Bill, which intends to reduce the risk of abuse to conservatees by increasing accountability and transparency standards for conservators.

The new law:

- ensures that a conservatee can choose their own counsel

- prohibits conflicts of interest concerning the conservator’s finances

- requires nonprofessional conservators to receive training on financial abuse and register with the state’s oversight agency

- requires conservators to disclose their fees online

- increases enforcement actions against conservators who do not act in their ward’s best interest

Assembly Bill 1663

In September 2022, the governor signed AB 1663 into law. The bill creates ways for people with disabilities to maintain their rights while still getting the support they need. AB 1663:

- recognizes and emphasizes supported decision-making

- makes conservatorship a last resort

- makes it easier to end conservatorships when needed

- ensures conservatees have choice in their lives, and as much decision-making power as possible

AB 1663 also created new programs to support these efforts:

- Conservatorship Alternatives Program, which would be present in each superior court and help identify petitions for conservatorships in which less restrictive alternatives, such as supported decision-making, may be appropriate to avoid the conservatorship.

- Supported Decision-Making Technical Assistance Program, a statewide program that would provide support, education, and technical assistance to expand and strengthen the use of supported decision-making.

AB 1663 also adds an amendment to the Welfare and Institutions Code (Sec. 16, Division 11.5), which establishes supported decision-making as an option under the law. Among other things, the law states that adults with disabilities must be given the opportunity to make decisions about their lives using as many voluntary supports as they need, including supported decision-making.

In a nutshell: AB 1663 offers families choice and a range of options. It requires that conservatorships are imposed only when it is the least restrictive option; it recognizes supported decision-making in California law for families who want something different than conservatorship. This can make supported decision-making more common practice in schools, Regional Centers, and doctor’s offices.

California Health and Safety Code & California Probate Code

As a result of AB 1663, section 416.7 of the California Health and Safety Code was amended, effective January 1, 2023, to emphasize supported decision-making. The amended code states that a guardian or conservator must work with the conservatee (and Regional Centers) as much as possible to develop and implement less restrictive alternatives to conservatorship. In essence, this code makes conservatorships a last resort and requires that supported decision-making be a significant part of the support plan.

Another code amended due to AB 1663 is section 1800.3 of the California Probate Code, which adds that before determining that a conservatorship is the least restrictive alternative, “the court shall consider the person’s abilities and capacities with current and possible supports,” including supported decision-making, powers of attorney, designation of a health care surrogate, or advance health care directives. The code reinforces the importance of supported decision-making.

The California Probate Code also amended section 1812, which determines a person’s conservator. The changes prioritize “the conservatee or proposed conservatee's stated preference, including preferences expressed by speech, sign language, alternative or augmentative communication, actions, facial expressions, and other spoken and nonspoken methods of communication.” This change emphasizes what AB 1663 has stated — that conservatees have a right to choice in their lives.

FREE Act

A bipartisan bill called the FREE Act has also been introduced to Congress. Its sponsors say it will reduce the risks of conservatorships by:

- giving a conservatee the power to petition for a public conservator

- assigning conservatees independent caseworkers

- requiring states to disclose the number of people in conservatorships to the federal government

- requiring that conservators disclose their finances

Critics of the bill say the FREE Act provides more funding to states for conservatorships, which “empowers professional guardians.” They also state that the bill doesn’t go far enough to protect people with disabilities.

The proposed Guardianship Accountability Act would create a set of best practices for states to use, share training materials with those involved in conservatorship cases, and offer a database of conservatorship alternatives.

MacCarley encourages parents to become active voices in the process and to share their opinions with their representatives by visiting findyourrep.legislature.ca.gov and www.house.gov/representatives.

What steps can parents take NOW?

Prepare for the transition IEP

Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), once students with disabilities start approaching the age of 18, they must go through a transition planning process with the school and their parents and/or guardians. An Individual Transition Plan (ITP) may be created as part of the IEP to prepare your student for life after high school.

Once they reach the age of 18, a student’s educational rights are transferred from their parents directly to the student. (A notice of this transfer must also be given to the student starting at least one year before their 18th birthday). When this happens, students can make their own educational decisions until they graduate high school or reach the maximum age for receiving special education services (21 federally, 22 in California). A conservatorship can assign educational rights to the Conservator.

In this situation, you can allow your young adult to retain their educational rights and self-advocate, petition for a conservatorship, or have the student sign an “Assignment of Educational Rights,” which gives you consent to continue involvement and make decisions in their educational program after they turn 18 (without a formal court order). Every path should take into account the best interest of the young adult, which may often mean including you, even after they turn 18.

Discuss your options

Before your young adult reaches the age of 18, it’s likely that you and the IEP team will begin to discuss conservatorship, and alternatives to conservatorships, during IEP meetings. The school may advise that you obtain a limited conservatorship to continue to be involved in your child’s education, which may or may not be appropriate in your situation. The transition to adulthood is complicated, especially for parents with kids with disabilities, and you may feel overwhelmed with all the options and information available. In these conversations, ask your school about conservatorship as well as the full continuum of decision-making supports, such as supported decision-making, durable power of attorney, etc.

Widen your circle of resources

While the school is a great resource, remember that they may not be able to answer all your questions, so it’s a good idea to discuss issues of concern not only with your IEP team, but Regional Center, your primary healthcare provider, relatives and friends you trust, a lawyer, and other professionals. With a support team, you can evaluate your child’s capacity to make appropriate decisions in each of the seven areas of power, either independently or with support. This way, you can explore your options and create alternatives that will help you protect your child as well as ensure their right to self-determination and independence.

Parent tips: what other parents have used when making the decision

When your child is 17 and a half, you probably won’t feel that they are ready for adult life. It's important to try to see this from your young adult’s perspective. Here are some things to consider and questions to ask and when making a decision about a conservatorship for your young adult:

- Think about how you were when you were 18 and the decisions you made for yourself at that age. Were you very independent or did you rely on your parents for guidance on most things (especially those that they were helping to pay for)?

- Talk to your parents or older family members about how they felt about letting go at this age.

- Talk to your other children about how they would feel about you making decisions on their behalf post the age of 18.

- Consider your child at 17: are they independent and impulsive? Do they want to make their own decisions or will they defer to your guidance?

- How easily could they be tricked? If someone asked them to sign a document, do you think they would? Would they give their money possessions away to someone else?

- Do they have a lot of contact with strangers, for example using online dating apps?

- Would they voluntarily leave with a stranger (perhaps not a stranger to them after grooming) and maybe consent to sex or even a marriage by themselves?

- If your child was in pain and needed a procedure but they were scared of it, would it be impossible to get them to agree to it?

- Are they determined to move out of your home without understanding what it takes to look after a home? Is it likely that they might elope and not be willing to return to your home, or that they might try to live in an unsafe place such as the street?

- Does your child get in trouble or hurt people due to their disability related behaviors? Are they likely to get arrested or questioned by police?

- In any of these situations, do you want the legal power to force your child to make the correct decision? How would it feel to exercise that right? How would you feel about someone else exercising that right?

- Can you make decisions for your child in areas of need through means other than a court-appointed conservatorship?

- If a conservatorship is necessary, in which areas does your child need your support and in which areas can they make their own decisions?

- Would you petition to be your child’s conservator yourself, or would you prefer someone else?

- What less-restrictive alternatives can you explore first?

- Do other professionals, therapists, teachers, or supports who have worked with your child recommend a conservatorship?

If you determine that your child does need a conservatorship:

If you’ve explored all the alternatives and have decided that seeking a conservatorship is necessary for your child, it’s important to start the process before they reach the age of 18. The process can take many months due to busy court schedules. If possible, speak to your child about your intent to obtain conservatorship and what that will entail. As Woodsmall explained, your child should play an active role in the process, voicing their opinions on what they are and are not capable of doing, and what areas of life they may need your help with. It’s also important to have a support team of trusted people and resources as you move through this process.

And speaking of support teams…

At this point in the process, you may have a ton of questions about conservatorships, the biggest probably being — where do I start? We’ve got you covered! Schedule a Kickstart to get access to our conservatorship guide (which will walk you through the process one step at a time) and one-on-one support from our Navigator team.

Learn how to set up a conservatorship for my child

More resources for families

Here are more resources to help you understand conservatorships and the responsibilities that go along with them:

- California Courts conservatorship guide

- Disability Rights California guide to limited conservatorships and alternatives

- Limited Conservatorship Guide: A User-Friendly Guide to Understanding Conservatorship for Adults with Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities from Bet Tzedek

- Judicial Council’s Handbook for Conservators (all conservators must have a copy of this handbook)

If you’d like to explore other related topics including the importance of person-centered planning, college programs, work training, community-based programs, independent and supportive living services, and public benefits, read our article on the transition to adulthood.

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor