IEP Due Process 101: Background, Preparation, and How to Approach Disputes

As the parent or caregiver of a child with an IEP, you will have received a long document setting out your procedural safeguards at every IEP meeting. (Whether you use it as a coffee coaster later is up to you.) This document describes your rights as a parent, from participation in the IEP process to what to do when you disagree with your IEP team. You’re probably aware that if you disagree, there is a “due process” system available to you to resolve the conflict. But what does due process mean in practice?

In this two-part series, we sat down with Dina C. Kaplan, a special education attorney at Vanaman German LLP, and Chris Arroyo, Los Angeles Regional Office Manager for the California State Council for Developmental Disabilities, to talk about the process of resolving educational disagreements. Here, we look at how to sign an IEP when you disagree with all or part of it, what due process entails, and the available options to help you resolve the dispute.

Background of due process

In 1971, most children with disabilities were excluded from public school. That year, The Arc of Pennsylvania sued the state to establish that children with disabilities had a right to an education. This was one of two legal cases in the U.S. District court that resulted in a remedy: the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (1975), which would eventually become the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA. The injustice being righted was that two million children had no access to public education; parents argued that this was a violation of their civil rights because the school districts treated their children differently without due process, which is guaranteed under the 14th Amendment of the Constitution.

This history means that at the core of IDEA, which forms the basis of federal special education law, there is a process for resolving disagreement over what an appropriate public education looks like in practice for each individual child with a disability. There is the Individualized Education Program (IEP) meeting in which parents participate. Beyond that, each state has an obligation to provide the means for resolving any disagreement between the student/parents/guardian and the school/district, usually referred to as a due process complaint (DPC).

IDEA Section 300 Subpart E sets out the safeguards and procedures for the dispute resolution process that all state education departments must provide.

How can parents prepare for due process with the school district?

Dina Kaplan advises parents to “document, document, document,” as “it is a very evidence-based system.” When you talk on the phone with the district administrator or case manager, you should follow up with an email that confirms that conversation. Set out in the email what you understood from the conversation, and any agreement or disagreement that was reached.

Chris Arroyo recommends ending your letter or email with a sentence along the lines of: “If anything in this email/letter is missing or incorrect, please let me know in a reasonable amount of time.”

Emails are sufficient in most cases, and you can request a “read receipt” to acknowledge that the email was read. You can also mail the district using certified mail or deliver it to the school or district office and ask the receptionist for a receipt.

Arroyo recommends writing letters or emails before, during, and after the IEP meeting. “Write a letter beforehand, stating that you have some concerns and listing the reasons, as well as stating the things you’re going to be asking for at the IEP. At the IEP, if you don’t receive a yes or no, be persistent and state that you didn't understand the response. ‘Was that a yes to my request, or a no to my request?’ I always recommend audio-recording the meeting so that there's a record of what was discussed. After the meeting, you can write another letter that memorializes what occurred at the meeting.”

Another reason parents should consider recording the IEP meeting is so that the record is available for an attorney to review, should the notes not be adequate. In order to record, you need to provide written notice (email is acceptable) to the case carrier twenty-four hours in advance of the meeting. Your district will also record the meeting. Using an email transcription service like Otter.ai can be useful, as it automatically generates a written record of the meeting.

If something seems off to you during the IEP meeting, it can be helpful to ask the person taking notes for the district to include it in the meeting narrative. This way, it becomes documented as part of the IEP.

To sign or not to sign an IEP?

If you come to the end of the IEP process and are still in disagreement, it is important to sign your IEP only partially, if this is allowed in your state, and write out your points of disagreement in a letter of agreement/disagreement. (Here’s an example of a letter of disagreement.) This letter then becomes part of your IEP. Signing partially allows those parts you agree with (for example, speech services and goals) to move forward while keeping the parts you disagree with on “stay put,” which means that the areas of disagreement will follow whatever is in the previously signed IEP. Hear this brief explanation of stay put from Undivided's Education Advocate Lisa Carey.

Dina Kaplan, a California attorney, tells us, “I always tell clients, even if you only agree with eligibility, to sign partially. I wouldn’t just not sign.”

This is important because when a parent refuses to sign an IEP, it means the district is obligated to continue to implement the old IEP, which may contain outdated goals and accommodations that the child has outgrown. Signing partially allows the district to move forward with those parts that you agree to, such as new goals, services, or accommodations.

In some school districts, the IEP form contains a section in the signature box for the parent to list their agreement or disagreement, as well as a place in each section (such as in the goals pages) to indicate agreement or disagreement. Where there is no place on the IEP form to indicate concerns, you can add your disagreement to the parent comments.

For other districts, there is usually not a place to list your points of disagreement. You should set out your concerns in a letter or email to the case manager and clearly indicate next to your IEP signature that your agreement is partial and that “this IEP should only be considered complete with the addition of the letter of agreement/disagreement dated (add date)”.

Dina Kaplan adds that if you don’t sign your IEP and the district feels it is unable to provide FAPE under the old IEP, the district may be obligated to file a due process complaint. If you partially sign, the district should respond in writing with their reasons for denying your request(s), unless they have already sent a prior written notice (a letter that sets out their reasons for denying your request) on the same issue.

How to approach disputes with your IEP team

When you find yourself in disagreement with your IEP team, what are the steps to take? It may depend on your IEP notes, which is one reason why it’s so important to carefully review your IEP before signing it. If you request a service or evaluation and the administrator or other team members say no, the reasons for their denial might not be clear in the IEP notes as written. In this case, parents should request that the district provide prior written notice.

Another way to diffuse the disagreement is to ask for a follow-up IEP meeting. You might ask for this meeting to be facilitated by a mediator or invite a professional advocate or attorney.

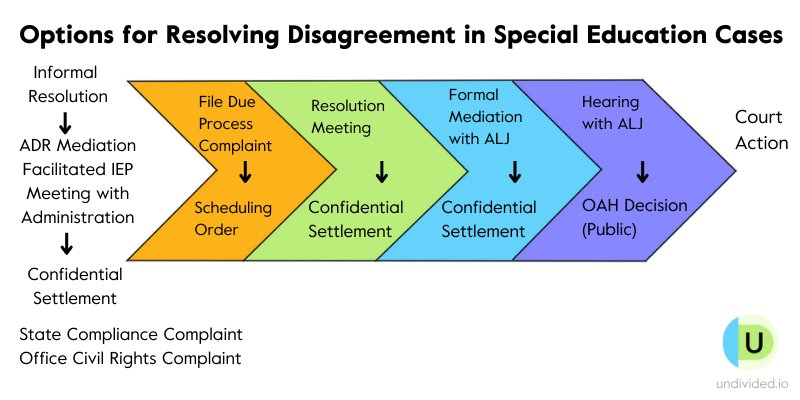

The most common way for disputes to be resolved is to have an informal resolution meeting with a district special education administrator. In smaller districts, this is usually the Director of Special Education. They have a lot of leeway to change the offer of FAPE. The resolution agreed on can be written into an IEP addendum, a letter of Prior Written Notice, or in a settlement agreement.

If you believe that your school is not implementing your child’s IEP as written, or that they have not followed correct procedures in the IEP process (for example, falling short on timelines to assess your child), you can also file a compliance complaint with the state department of education. A compliance complaint is different from a due process complaint. While it can take a long time for the state department of education to investigate a complaint, these same issues might form part of a due process complaint and be settled sooner.

If you believe that your child has been discriminated against due to their disability (or also race, national origin, ethnicity, or gender), you may also file a civil rights complaint with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights. In both cases, this is a good way to address a systemic issue involving a number or group of students being unfairly treated in the same way.

Often, the best first step is to ask the special education director (in smaller districts) for an informal meeting to resolve the dispute.

In California, you may also utilize your Special Education Local Plan Area (SELPA)’s Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) service to provide a mediation meeting. Using ADR does not impact your parental rights to later utilize due process if your disagreement is not settled in the informal meeting. In California, all SELPAs must offer the ADR option.

Confidential settlements for an IEP dispute

A successful informal meeting or mediation is likely to result in a confidential settlement agreement between you and the district. It is common for these settlements to include clauses that waive your child’s educational rights. Often, this means you cannot go to due process over the same issue for a specified period of time. Sometimes, the settlement may contain a prospective waiver that covers the district against any litigation for the rest of that school year or annual IEP. Dina Kaplan tells us that it is wise to consult an attorney to make sure you fully understand the implications before agreeing to any waiver.

Although Chris Arroyo is not an attorney, he worries about provisions that commonly appear in settlement agreements, holding the district unaccountable for anything that's ever happened up until that point in time. “That's a powerful release,” Arroyo says. “My recommendation would be that if something is happening outside of the IEP process, there's no reason why it cannot be memorialized in an IEP amendment, and an addendum.”

The confidentiality of the settlement can also be problematic. You will need to be especially careful not to write about your settlement in any public forum or on social media. The agreement may be invalidated if it is shared with anyone outside of the team members needed to implement the agreement. (It can be shared with your IEP team.)

Commonly, such settlements also require that you waive the “stay put.” In other words, if you and the district are still in disagreement at the end of the settlement, then the default position will remain that of your last signed IEP. If you sign partially, the “stay put” will be the last IEP signed for each section.

If your settlement is not honored, the Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH) will not enforce the agreement. You can file a compliance complaint, or go to a state or federal court to enforce the binding contract.

File for due process

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor