What to Do When Modifications Aren’t Working as They Should

It can be frustrating for families who have advocated for modifications to support their child's learning, but see their child continue to struggle. Modifications provide access to the general education curriculum by changing the expectations of what a student learns, rather than how they learn. For example, a teacher may modify an essay-writing assignment by making it significantly shorter or about a less complex topic. While all students should have access to the general education content, some may need alternative, aligned achievement standards. (Note: in this article, we are referring to modifications as custom designed instructional materials or assignments that focus on alternative achievement standards for your child, and are aligned with the schoolwide curriculum.)

Who’s responsible for ensuring a student has the right modifications in place? And as a parent, what can you do if the modifications in your child’s IEP aren’t effectively supporting their learning, or if teachers aren’t implementing them consistently? We spoke to special education advocates and other experts to get their advice on steps you can take.

4 reasons your child’s modifications might not be effective

If you feel modifications are happening but aren’t as effective, the first step is to assess if the modifications are still a good fit for your child. Here are a few ways a modification might not be effective:

1. If the modifications are not appropriate — either too easy, too hard, or not visually accessible:

Modifications may be ineffective if they aren’t age appropriate, or either too challenging for the student, or too easy. This can happen with growth over time, or if the child wasn’t assessed properly. A lot of kids shut down when given work that they see as too easy or “babyish.” This can happen if the modification is for a lower grade level and uses preschool cartoon characters; some older children are going to be put off by this and not engage. Some modifications are also not visually appealing or accessible to students if, for example, the fonts on a worksheet are too small, frilly, or overly crowded.

Arielle Starkman, an inclusive education consultant in Los Angeles, tells us that the one place many teachers or providers overlook when it comes to modifications is how they're visually presented:

Undivided Non-Attorney Education Advocate Lisa M. Carey gives us a few steps of where parents can begin to troubleshoot: “Start by asking your child’s teacher(s) questions: ‘Who decides what modifications are needed?’ ‘Who creates them?’ ‘Are they at the student’s independent reading level or grade level?’ You can also ask to see work samples to make sure they are age appropriate. Not being able to do grade-level work does not mean the work should not be age appropriate. If your child is in middle school, they should not be reading Dr. Suess, even if that is their reading level.”

Questions to ask:

- Does the modification use images and themes that engage my child?

- Is the modification age appropriate?

- If the modification presents reading at the child’s instructional level, has the teacher adequately tested their reading level to have a sense of what would be challenging?

- Is my child bored with what and how they are learning? Similarly, are they struggling to complete their assignments even with the modification?

- Can I review some examples of modified work to ensure it aligns with my child’s needs and interests?

2. If the modifications exclude a child from their peers:

Another way a modification might not be effective is when it impedes inclusion, or a child feels left out. Often when modifications utilize worksheets from an out of the box program they may be dislocated from the core content that everyone else is doing. Differentiation needs to make use of the core content. For example if the rest of the 4th grade class are learning about California History and the missions, but your student has a work assignment from an out-of-the-box solution that is about the early development of the car industry. It may be that all the class is working on an essential standard to understand that history relates to events in the past, but you are asking a child to make connections between two very vaguely linked historical topics.

As Starkman explains, “If modifications are truly being provided, usually there's someone thinking in-depth about how to connect the curriculum and the students' needs. For a lot of students that we see, either those modifications aren't provided or something is being provided that is deemed modification, but it's not in alignment to the grade level curriculum at all. And students could be doing that in isolation at the back of the classroom. Or, maybe there's partner work happening in the class but because the kid is working on something so different, there's no way that they're able to kind of engage in that, and they're not provided with that opportunity.”

Questions to ask:

- Is the modified work sufficiently aligned with the core content presented in class?

- Is this modification promoting or impeding inclusion in the gen ed classroom?

- What processes are in place to ensure my child isn’t working in isolation on unrelated tasks?

- How does the teacher ensure modifications are thoughtfully designed to meet both my child’s needs and the class content?

- Does your child's general education teacher provide their input when modifications are created?

You can direct the teacher making the modifications to the Core Content Connectors wiki to support them in creating modifications that are aligned with what the rest of the class is doing.

3. If the modifications are in separate classes:

Many students are in separate special education classes where a functional curriculum is taught. Although the students in an “alternative curriculum” class are not expected to reach grade-level standards, they should still be working on a curriculum that is aligned with their grade level and includes grade-level content, similar to students that are in other classes in the school The teacher will need to do a very high level of differentiation to cope with each of her students being at different levels for different skills and may have a span of multiple grades such as K-2 within one classroom. In reality, it is rare that this differentiation happens.

It is important to make sure that your child’s work is modified to align with their grade-level standards and also to tie into their IEP goals, which can be worked on all day, anywhere, not just in a separate Specialized Academic Instruction (SAI) setting. It's a delicate balance but it's important that the work is challenging, as close as possible to the grade level standard, moving the child through the grade levels, and engaging for your child.

Questions to ask:

- How is my child’s curriculum aligned with grade-level standards while still meeting their individual needs?

- What steps are taken to ensure my child’s work is both challenging and engaging?

- How are modifications made to align classroom work with my child’s IEP goals?

- How often is my child’s progress reviewed to adjust modifications or goals as needed?

4. If the modification don’t help a child work toward IEP goals:

Often when kids are included in general education the focus of the modification is just to make engagement in the grade level content meaningful and productive. But if the child is not working on their IEP goals, is there any educational progress to come out of this engagement? Do the modifications relate to the child’s IEP goals?

For example, your 7th grader is learning to take notes in science — the teacher is speaks to them and they are supposed to take notes in a certain way. Your student has a modification that is the use of a scribe, meaning their aide will take the notes for them. Note that a scribe can be both an accommodation and a modification depending on context — but in this case the students are learning to take notes, so writing is what they are learning, not just how they are learning.

So during this long lecture, the student sits while the aide furiously tries to keep up with the note taking according to the format the teacher prescribed. What good does it do for the student if they aren't engaged in the class, and probably not paying attention; they are not learning anything about note taking except that they cannot and are not expected to do it. They aren’t practicing their IEP goals which might be focused on reading at their instructional level, or communicating with peers.

A much better modification would be for the teacher to create a sheet of simplified notes (at their reading level) in the correct format and have four or five words stand out that the child has to listen for and circle when they get there. The child should have an opportunity to read through it once before the lecture starts. They can circle one word or from a field of three. They might even have to put their hand up and tell the class, “Make sure you write that down!” This means the child is paying attention, listening, organizing the information, and reading, and communicating by circling/giving instructions to their peers.

Questions to ask:

- How do the modifications in my child’s general education classes support their IEP goals?

- Are there modification opportunities that will allow my child to actively engage in learning tasks, rather than just observing or relying on support from an aide?

- How are modifications designed to keep my child involved in the lesson and promote active participation?

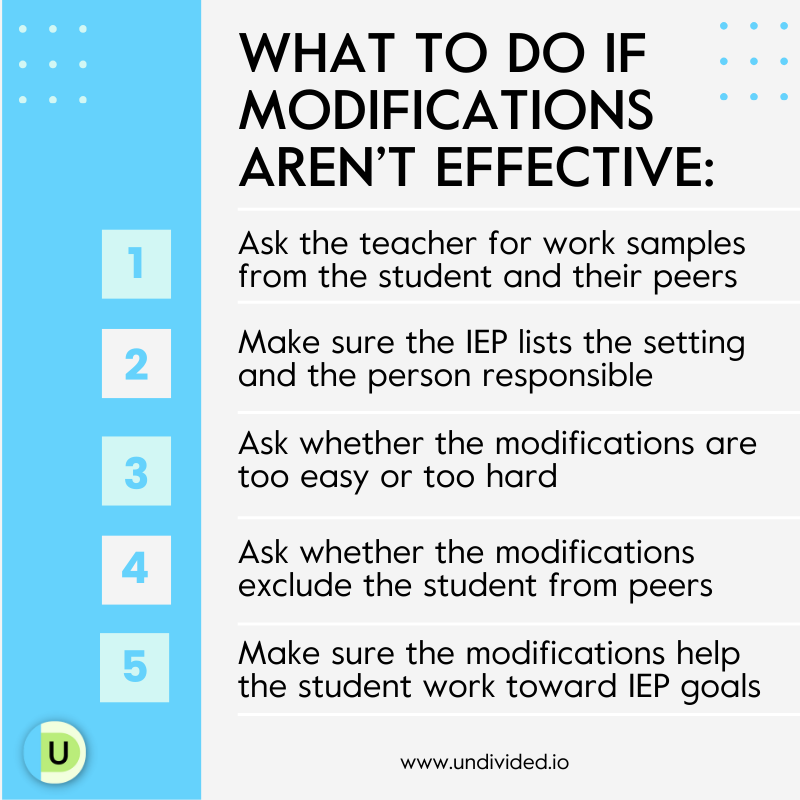

What to do if the modifications are happening but aren’t effective

Speak with your child’s teachers

If you become aware that there are modifications that were agreed in the IEP that are not effective (or aren’t even happening), always start by talking to the teacher (or teachers) who is responsible for implementing them. You can review the modifications section of your child’s IEP so you have a better idea of how the teacher is and is not implementing them. Make sure to document and take notes on which modifications aren’t being provided.

Carey recommends having direct conversations with your child’s teachers and service providers. Ask specific questions and discuss any aspects of your child’s IEP that aren’t being followed. Who decides what modifications are needed, and who creates them? Are they at the student’s grade-level? Are they age-appropriate? Why aren’t they being implemented? What steps can be taken to ensure they are moving forward? An informal meeting can be a great way to open up dialogue and work toward a solution.

For example, if your child has a modification that allows teachers to assign them essays that are shorter or about a less complex topic, you can ask their teacher, “What essay is my child working on compared to the rest of the class?” You could also ask, “Are you automatically assigning them a modified essay, or are they having to ask you for it?” Asking prompting questions can give you a good idea of what is going on and alert you to any red flags, such as the teacher being unable to answer your questions. By opening a dialogue with your child’s teacher about specific details of their IEP, you may find that some modifications are working better than others.

Also note that it’s not up to parents to modify something on their own; that’s the teacher’s (and IEP team’s) job. It’s also up to the teacher to determine what the student learns and how they are assessed, so if you are modifying homework, you may be overstepping. If you do have ideas of modifications that would help your child, bring the sample to your IEP to show the team what you have in mind.

Check in with your IEP team about what is and isn’t a modification

As we discussed earlier, many times, something is being provided that is said to be a modification, but it's not in alignment to the grade level curriculum. It’s important to keep open communication with your IEP team and bring up these concerns. As Starkman explains, “When modification is deemed as totally separate and different, we have a problem. I've been in schools where teams are trying to figure out how to bring in a packaged special education curriculum into the gen ed setting that's not aligned with what's happening in the classroom. So we have to rethink that. I also see schools try to pull workbooks and different things that are out of grade level, saying, ‘Well, this is this is modified,’ and it's not.” Starkman’s advice: talk to your IEP team. “We really have to come back to ‘What are curriculum modifications?’ with our IEP team. And once we can kind of delineate how that's different from some of these other purchases, we can start having a conversation about what that will look like, who will be responsible for that, and how I'll be implemented.”

Make sure modifications are listed in IEP for all the settings you want them to be used in

If you want modifications to be present in all settings — PE, electives, performances, presentations, field trips, independent work time, etc. — make sure the IEP lists it that way. Sometimes, parents note that a modification is done in certain settings but not in others, so kids aren't having access to everything throughout the day. As Special Education Advocate, Dr. Sarah Pelangka, BCBA-D, says, “With modifications, if you look at the IEP, it does ask you to specify for what subject, so if it's not written as such, then they're not going to implement it as such. You can't just assume it's going to be everywhere. So you want to make sure that's clearly documented within the IEP.”

Make sure the right people are responsible for implementing the modifications

Sometimes modifications are listed in an IEP without a particular team member being responsible for providing them. “Doing the modification” is a complex task. Review your child’s IEP and make sure there is a specific person responsible for every listed modification. For example:

- A general education teacher’s input is nearly always required because it is their materials that are being modified, and a gen ed teacher may be the person implementing the modification.

- It might be a special education teacher’s role to plan the modification and create materials.

- Teachers might train a paraprofessional to do the work. Instructional aides are often involved with modifications. Sometimes, they are presenting the modified materials to the child. They may also be working to create a word bank in Clicker or using velcroed laminated words. Quick-thinking aides also often ‘modify on the fly’ when they see the child is puzzled or frustrated with the instructional level. This is also a useful skill for parents to learn! However, the paraprofessional and parents should always be modifying under the guidance of the special education teacher responsible for modifying the child’s curriculum, so it is clear how much help is provided and how the child’s assignment will be graded.

Listen as Starkman explains this more about best practice for an IEP team in terms of who should be making the modifications and who should be implementing them:

As parents, even if we know who should be responsible, it can often feel hard to know what to do, what questions to ask, or how to advocate for our kids when it comes to this topic. Carey tells parents that IEP’s can have consultation time added into the supports section when it comes to modifications. For example, “It is important that the general education teacher and the special education teacher have adequate time to collaborate with each other. This collaboration is hopefully authentic and not performative, meaning they are truly working together to make sure modifications are age appropriate and aligned with the general education standards.”

In the clip below, listen to the Non-Attorney Special Education Advocate and Undivided Content Specialist Karen Ford Cull; Undivided Navigator and Independent Facilitator Iris Barker; and Undivided Head of Content and Community Lindsay Crain talk about how best to keep track of what is happening at school and who to keep accountable when making modifications to your child's curriculum.

Ask for curriculum and work samples

If your child has modified work written into their IEP, how do you follow up on how well those modifications are working? You should ask for your child’s work samples, of course, but Dr. Pelangka also recommends asking the teacher to see the original unmodified work too to compare. You can always ask for progress reports to get more information.

Dr. Pelangka explains, “Modifications can absolutely be an excellent way for students to access [to the general education curriculum], but make sure that that is what's happening, because it's hard, and it's very rare that I see it being done right. And so that's where I say, ask for what the rest of the class is getting in comparison to what your child is getting to make sure that they are still accessing the grade level content.”

Listen why in this clip, and hear her recommendations for how often to ask for that work to be sent home:

Dr. Pelangka also notes that if your child has modified work written into their IEP, “Specify for what subject. You can't just assume it's going to be everywhere. So you want to make sure that's clearly documented within the IEP.”

Ask for an ecological participation report by an inclusion specialist

An ecological participation assessment/report by an inclusion specialist can provide vital information for your IEP team on modifications that are needed or modifications that need to be provided differently. This is still a new idea in many respects and there may be some confusion about what you mean. State clearly that you want to have an expert observe your child during general education instructional time and write a report on what supplementary aids and supports might be added to make their inclusion more successful. This report should not be an assessment of placement, or even of your child but an assessment of the environment to see what might be added. Many districts are hiring their own inclusion specialists or they can contract with a company such as 2Teach, Arielle Starkman, or Sevi’s Smile. For more information, see our article Inclusion Specialist 101.

Advocate for your child — your voice matters!

Modifying schoolwork for a child with multiple challenges is no small task — it’s often a trial-and-error process. Many special education teachers may not have specific training for working in inclusive settings or with children who share your child’s unique diagnosis. On top of that, their time with your child may be limited, leaving little opportunity to figure out what strategies are most effective.

This can be especially tricky in high school, where special education teachers might lack the subject expertise needed to align content in a meaningful way. Under time pressure, teachers often rely on pre-made worksheets or “out of the box” curriculum resources.

As a parent, you play a key role in advocating for what your child needs. This might include asking for more collaborative planning time, additional push-in support, or better consultation between the special and general education teachers. If your budget allows, you might also consider purchasing adapted materials from resources like Teachers Pay Teachers to help bridge gaps. By showing support and understanding of the challenges teachers face, you’ll likely find your voice carries more weight as a valued member of the IEP team.

What to do if the agreed modifications just aren’t happening:

What do you do as a parent if, on the other hand, teachers or providers are inconsistently implementing the modifications that are already in place in the IEP?

Gather information

The first step is always to gather information and keep an open mind. There may be things happening in school that you don’t see as a parent, so start off by asking your IEP team, and your child’s teachers, some questions. Carey tells us that parents can start by figuring out why they’re not happening: “Start by asking open-ended questions to the teacher. Ask who is doing the modifications (the teacher, for example) and if there is adequate planning time in their schedule.” Lets explore some more steps.

Here are some ways you can gather information:

- Ask the teacher how your child’s modifications are being implemented

- Ask the teacher to see samples that show modified work

- Request a classroom observation (you will likely be given a time limit and be accompanied by an administrator or staff member). This is a great way to see how their modifications are being put into practice. If you can’t observe in person, consider asking or hiring someone you trust to do it for you. Keep in mind that some schools are more open to setting up observations than others, so it’s a good idea to talk with your child’s teacher or principal ahead of time.

- If you can, ask your child about the particulars, especially if they are older. For example, if their IEP says a modification they should have is reading an abridged version of a novel in English class, ask your child whether they are. If they say no, you can reach out to the teacher to find out why. It can also be a great way to educate your child on what is in their IEP and encourage them to advocate for themselves.

Gathering information will help you understand whether the issue is lack of implementation or that the modifications themselves are not helping.

Call an IEP meeting

If the IEP is not clear, you can call an IEP meeting (making sure the teacher is present), which will take 30 days and a lot of staff time, or you can ask the case manager if you can make an amendment over the phone. It may be something simple like adding who is responsible for creating the modifications. It’s also a good idea to set up a team check-in about thirty days after the initial meeting to see how things are going and ensure that the issue was truly resolved.

Get it in writing

If it continues to happen that you have modifications documented in the IEP that do not happen, then put this in writing with a polite letter to your IEP team. It’s important to get everything in writing, whether it’s an email, letter, phone call, IEP meeting, etc. For example, after speaking with a teacher, district administrator, or case manager on the phone, it’s important to follow up with an email to confirm the details of your conversation. In the email, summarize your understanding of what was discussed, including any agreements or disagreements that were reached. In most cases, emails are sufficient, and you can request a “read receipt” to confirm that your message was read. Alternatively, you can send a letter via certified mail or hand-deliver it to the school or district office, asking the receptionist for a receipt.

Get support from advocates and attorneys

You might also consider enlisting the support of a special education attorney, or an advocate if you feel you need support understanding your rights or navigating the system.

- Advocates can attend IEP meetings, help you to understand test results and IEPs, and assist you in filing state complaints.

- Attorneys can give legal advice and assist you in filing due process.

- Both advocates and attorneys can help you reach collaborative solutions with the district, review documents, and understand your rights. They can also send letters or emails on your behalf.

Resolve a dispute with my IEP team

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor