Child Life Specialist 101

A child life specialist can be an important extension of a child’s care team during a hospital visit. Most hospitals have child life specialists who are educated and clinically trained to work with doctors, nurses, and you and your child throughout your child’s care. They are there to help kids and families cope with the stress, uncertainty, fear, and anxiety that can arise during hospital stays, medical experiences, and more. This might involve emotional support, advocacy, education, play, and more. To gain expert insight into what a child life specialist is, what they do, and how they support families, we spoke with Rachel Delano, a licensed clinical social worker and a certified child life specialist, and Katie Taylor, a certified child life specialist and CEO and co-founder of Child Life On Call. We also spoke to two parents of medically complex children: Undivided Navigator Heather McCullough and Katherine Lauer, mother to a medically complex child who spent months in-patient and benefited from the CCLS services.

What is a child life specialist?

According to the Association of Child Life Professionals (ACLP), “Certified Child Life Specialists (CCLSs) provide evidence-based, developmentally, and psychologically appropriate interventions including therapeutic play, preparation for procedures, and education that support and reduce fear, anxiety and pain for children, adolescents and families. They work in partnership with families, interdisciplinary healthcare teams, and community professionals within the evolving healthcare system to meet the psychosocial, emotional, and development needs of children and adolescents.”

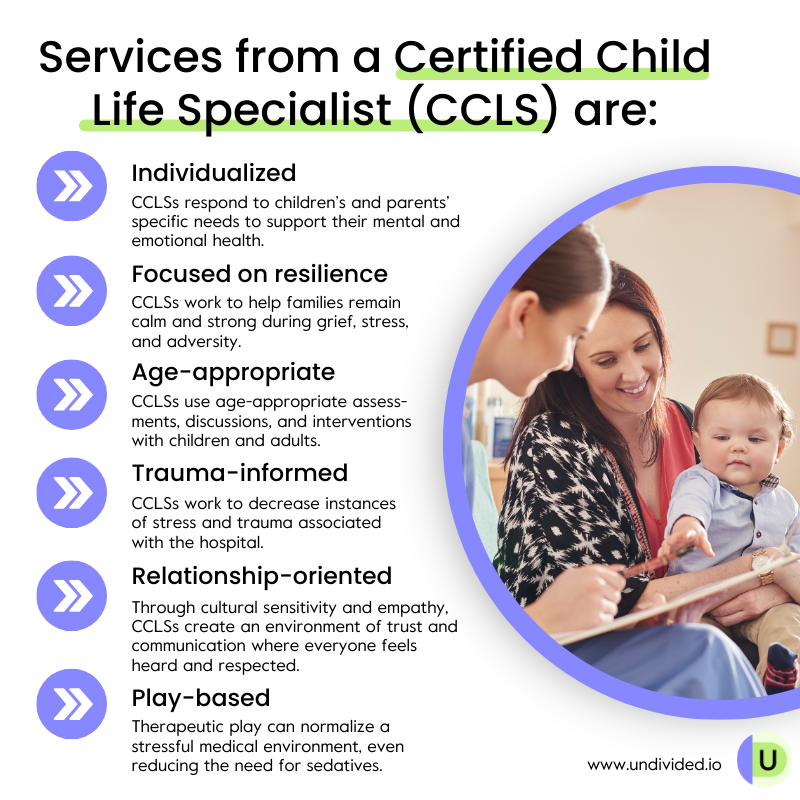

While we mainly focus on CCLSs within the hospital environment, child life specialists work in various departments and settings, such as emergency rooms, inpatient and outpatient units, schools, camps, dental offices, and even the home. They also have many duties (which can vary day-to-day) that, according to the ACLP, fall into six evidence-based domains meant to support families: CCLSs use an individualized approach, focus on resilience, factor in age and development, and are trauma-informed, relationship-oriented, and play-based.

A child life specialist assessment

When you first meet with a child life specialist, they will ask you many questions to assess the psychosocial aspects of your family’s situation, and your needs. A tool they may use is called a psychosocial risk assessment in pediatrics (PRAP), used to “assess pediatric patients' risk for experiencing distress during health care encounters.” Katie Taylor explains what you can expect from a psychosocial risk assessment with a child life specialist:

“If you come to the emergency room for stitches, you might be with a child life specialist for anywhere from 10 minutes to an hour. As a child life specialist, we go through a mental checklist of something that could be called a psychosocial risk assessment where we consider different factors that can affect a child and family’s ability to cope. Some of the things we consider are: The age of the child, What is the reason they’re here and what type of pain will they be exposed to? How many times have they been there before? What does their support system look like? This checklist helps us decide what interventions we'll offer to this family. So, sometimes it's as simple as walking by, saying hello to a family, seeing how they're doing, and ensuring that their needs are met. Do they feel safe in the hospital? Do they feel informed? What can I do for this child to normalize the environment, and it may be as simple as bringing over a few toys. Ultimately after this initial assessment, I can determine how long I should stay and when I can go to my next patient.”

According to Taylor, Child Life service is a choice but encourages families to ask for one because families don’t know how one can help until they experience it.

How do child life specialists help families?

Whether your child is in the hospital for a day, or a few months, the presence of a child life specialist can significantly impact their overall hospital experience, turning it from a challenging experience into a more positive one. Rachel Delano says to think of them as liaisons who interface between medical providers and families. "We are there to help guide the parents and children through the experience in ways that they can understand," Delano says. Below are some things a child life specialist does to help families.

Provide education and support

Preparing kids for medical procedures

Child life specialists are family-focused and can offer education and support in a variety of ways, including helping kids prepare for medical procedures, talking through and supporting families during and after procedures, providing distractions for kids during procedures, and teaching tips and strategies for coping with fear or anxiety.

According to Delano, CCLSs can be requested when there is a perceived threatening event that may be traumatic for some children, such as during blood draws, IV placements, stitches, new diagnoses, surgeries, X-rays, MRIs, chemotherapies, extended hospital stays, and sleep studies. For example, when there is an upcoming medical procedure, a child life specialist will help kids by modeling parts of the procedure, engaging in medical play with medical equipment and dolls, and role playing. Child life specialists may even use medical play with hospital-related toys like bandages and syringes to help kids become familiar with the items they may see in the hospital and during their procedure in a non-scary way.

During procedural support, CCLSs use age-appropriate active and passive distraction strategies to develop a coping plan that reduces possible pain and trauma during the actual procedure. Active distractions might include using virtual reality or a kaleidoscope. Passive distractions can include watching cartoons and listening to music.

Delano provides a typical conversation a CCLS has with a child who takes out an IV. She tells us, "Child life specialists validate the feelings of discomfort and worry while also educating them. Affirming statements are huge. First, validate the child's fear, worry, or concern. Then, provide honest education about what would happen if they acted on it without shaming them: 'I hear that you really don't like having the IV in your arm. While we stay in the hospital, it has to be there to help you get better. The nurse should be the only one who touches it. If you decide to take it out, we would need to put a new one in.'"

CCLSs support children who have more aggressive refusal tendencies beyond pulling out an IV as well. According to Taylor, there’s no cookie-cutter approach, as each case is unique. In cases that require more support, Taylor says the behavior indicates something else might be going on, such as a sensory need, an underlying trauma response, a misunderstanding, or something else.

“Child life specialists help de-escalate these encounters and try to find the root of the issue to improve communication from the child to the care team,” she says. “Child life specialists use methods and interventions to avoid restraints whenever possible. In some cases, child life specialists would advocate for the parent to communicate with the doctor about pharmacological options to reduce anxiety over the use of restraints.”

Delano adds that, “There are times that children are not going to cooperate, and that is when firm language and parent support need to occur. This includes validating a child's feelings and needs while reinforcing what needs to happen to provide appropriate medical care for the child. For kids with extreme sensory challenges, we try less is more. Patient safety and staff safety is a priority, and no one wants to be put in an unsafe situation with a needle. ONE VOICE is a popular choice for only having one person speak throughout to help eliminate noise and working with the child so they know each person's job.”

The ONE VOICE approach teaches “health care professionals how to create a less-threatening environment for children during medical procedures.” According to Debbie Wagers, a CCLS and creator of ONE VOICE, the acronyms stand for the following:

- One voice should be heard during procedure

- Need parental involvement

- Educate patient before the procedure about what is going to happen

- Validate child with words

- Offer the most comfortable, non-threatening position

- Individualize your game plan

- Choose appropriate distraction to be used

- Eliminate unnecessary people not actively involved with the procedure

Both Delano and Taylor agree that each case is unique. The strategies used depend on the situation at that moment.

Pain management

CCLSs can also help kids cope with pain and anxiety. They may offer suggestions to parents, such as comfort positioning, a technique often used during procedures like injections to calm a child down. The way a child is positioned can help induce comfort during injections or related medical procedures.

They can help with acute and chronic pain management as well. Delano says, "For acute pain, we work on deep breathing exercises to help cope until pain medication is available. We can also provide guidance around non-pharmacological options, such as distraction, an ice pack on the chest, a hand massage, and a parent or guardian close for comfort. This is in addition to providing developmentally appropriate education around next steps and how pain medication may be delivered." Other coping tools Delano says child life specialists can have specialized training in and provide include 54321 grounding methods, M-technique, massage, and aromatherapy.

Diagnosis and treatment education

CCLSs also provide diagnosis education to help families understand and manage a new diagnosis. Delano says honesty is critical: "We're huge on being honest because kids aren't always told the truth. And we really want to empower families to tell their children the truth so they know what to expect. Even if they don't like what's going to be said, they don't feel tricked."

Taylor adds that when it comes to talking to children about what is happening, “Often you'll find that the child leads the way. So kids tend to ask the questions that they want to know the answers to. And maybe when they're not ready to hear or ask a question, they're not ready to hear it.” For example, if a child is diagnosed with diabetes, “We want to make sure they understand their diabetes and why they have it; but the child is processing a new environment, a new treatment plan, new people all around. They may not be quite ready to understand what diabetes is and why they have to have this shot. But those questions will come. And so it's just about being really good at listening to your child's needs.”

Child life specialists are trained to explain things like a diagnosis to a child in a way the child can understand, whether that’s through conversation or role playing. Role playing with medical equipment or play kits, for example, helps kids process what they’re learning about their hospital stay and diagnosis.

"We naturally as human beings want to diminish uncomfortable feelings," Delano says. "So when our kids tell us, 'That was scary for me,' We typically say, 'But you were fine. And look at what happened next.' Instead, say something like, 'That was scary. And then these are the things that we did to help that scary situation.'" And if your child is prescribed new medication, a child life specialist can help come up with strategies for medication management and how to navigate medical care at home.

Promote child enrichment and play

Play is one of the most important ways a child life specialist can help your child. And just because your child is in a hospital doesn’t mean they’re not going to want to play. A CCLS will often incorporate age-appropriate play activities in every area of support, from helping with procedure education to making another long day in the hospital room a little more fun.

Normalize the hospital stay

CCLSs are very involved, hands-on, and trained to respond to many needs. They can help normalize being in a hospital, or getting a medical treatment, whether that involves keeping special days special, or providing kids with their favorite toys from home. For example, if there is a holiday, special event, or birthday coming up, a child life specialist can help you celebrate. This helps kids keep a sense of normalcy, even when they’re in a hospital. So don’t hesitate to ask for party supplies, toys, decorations or anything else to make a special day special.

McCullough, who has used Child Life services for over six years, says CCLSs have alleviated much of the stress for her as a parent. When she gets ready to go to the hospital, she prepares her daughter ahead of time. Her daughter usually knows they're heading to the hospital when she sees her parents packing their bags. Delano says, "If parents are going to the hospital or doctor's office, pick out a few small items that can be utilized for distraction. You want these items to be special and not utilized every day so they can hold your child's attention (e.g., a new book, coloring items, small bubbles, light spinner toys, play figurines, magnetic pictures, etc.)."

But sometimes, you may not have time to pack everything you need — don’t worry, you can also request favorite toys and activities. McCullough recalls a moment when her family requested bubbles for her daughter. Her daughter loves bubbles, and when one hospital didn't have bubbles, the CCLS went out of her way to get them. That made all the difference.

Offer therapeutic medical play

Therapeutic medical play is another way child life specialists help kids to get more comfortable with their hospital stay and cope with medical procedures. This happens through, “The 1) the encouragement of emotional expression (e.g. re-enactment of experiences through doll play), 2 instructional play to educate children about medical experiences, and 3) physiologically enhancing play (e.g. blowing bubbles to improve breathing).” Medical play also helps foster more positive behavioral responses to future medical experiences.

Help kids be kids (not patients)

Undivided Navigator Heather McCullough tells us that Child Life is a huge resource she recommends for everyone facing an extended hospital stay. They not only offer support, but they help kids be kids, even when they’re in a hospital, whether that means doing arts and crafts, playing games, coping with therapeutic play, music therapy, art therapy, and pet therapy, or just getting a boost in morale.

School re-entry

Children often experience school separation and isolation from their peers after a prolonged absence. CCLSs use educational re-entry programs and play-based therapies to reduce these feelings children may experience. They can come in to motivate kids to keep up with school during extended hospital stays.

Support parents and siblings

While a child life specialist’s main focus will be your child, they are also there to equip parents with tools to best support their kids through the medical process (and the parents’ emotional needs, too). "I think people always think we work with just kids," Delano says, "but there's so much family work. It's a lot of parental support and education." It’s stressful for parents to see their kids in the hospital and a CCLS can help lower that stress. Parental engagement is also believed to help a child cope better.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed and need support, ask for a child life specialist. Even if you don’t remember the specific title, but you know you need help, Katie Taylor, who was a CCLS for 14 years before co-founding her company Child Life On Call, suggests letting a nurse know you need support: “I would also urge the parent if they are feeling like they're in a crisis or fight-or-flight mode, to just ask their nurse, ‘Who is a support person here who can help me?’” Taylor says. “You don't have to remember the term child life specialist, but that will indicate to the nursing staff that you need a social worker, child life specialist, or even a chaplain or spiritual care who can come by and check in on you.”

For example, CCLSs provide grief and bereavement education and support. For families who may experience the loss of someone close to them, or need help coping with the grief of having a child in the hospital, CCLS will interact with them in developmentally appropriate conversations and connect with grief or bereavement support groups.

Taylor adds, "I want to be there for your family and support you, but I ultimately know that you don't get to take Child Life home. I want the skills you learn from Child Life to impact the way that you're able to parent your child, support yourself, support your community, learn how to advocate. And so over time, if you have to return to the hospital, you feel more empowered yourself. And, of course, Child Life will be there and always happy to be there. But we want to see families feel like they can handle whatever comes at them because they've been taught the skills on how to feel empowered.”

Through her experiences, Taylor found that families who feel empowered, know how to advocate for their child, and have a support system have "had much better not only experiences, but better outcomes in the hospital," she says.

Parent empowerment

While it is important kids learn to speak up and advocate for themselves, there are occasions where parents must step in. Typically, that’s when the kids are too young and aren’t able to and when they are in a vulnerable position or struggling with major health challenges. CCLS will assess the situation and use their skills to determine if they need to go straight and talk to the parents or caregivers or to the child first.

Delano encourages parents to speak up and ask their providers if they disagree with a treatment plan. She educates parents on how to ask the medical providers for an alternative solution, such as "What would be a couple of other options so we can make an informed decision about what would be best for our child?"

Delano also tells us, "I always tell a family that at the end of the day, they are their child's voice, and even if [they] don't like the answer, [they] don't have to wonder ‘what if.’ During medical procedures, CCLSs can advocate for a break for the patient, a different provider to try the procedure, and a new plan if it is not going smoothly."

Taylor tells us her take on not only supporting parents, but helping them build skills they can use in the future. She says, "If you can think of a teacher who's teaching their third grade students how to do multiplication, at the beginning, they need a lot of teacher intervention so that they can learn how to do it. But ultimately, we want them to know multiplication on their own, and to carry it with them forward. So I really like that analogy for Child Life services. Listen to how we prepare your child; some of the terms that we use; how we break down complex information into more simple terms. So the next time a challenging life event comes up, whether it's a divorce, or a death in the family, or the death of a pet, or something happens in our world or society, you can pull on some of the things that Child Life has taught you, to take these kind of scary, complex things, to always tell the truth, how to do it honestly, how to do it simply, and how to ultimately impact that parent and child bond."

Sibling support

Having a sibling in the hospital can be very difficult to cope with. A CCLS can offer sibling support to help them understand what’s happening to their brother or sister and use resources to help them cope. “Sometimes they are the unrecognized child in the situation,” Katie Taylor says. “So it's really great when they can have those feelings of ‘I feel seen. Someone is thinking about me, and the way I feel matters.’”

McCullough shares how a CCLS helped her kids cope with their sibling’s hospital stay. She says having a CCLS helped mitigate any traumatic experiences her sons might have experienced from seeing their sister hooked up to machines and whatever else they might have picked up from being in a hospital environment.

McCullough shares an example: when her daughter was born, her son was 6 and didn't want to hold his sister. She thought he was concerned about hurting her, but after a CCLS was brought in, he revealed that he was afraid of catching whatever his sister had. The CCLS helped assure him he was safe and used techniques to minimize his fears. Now, he's his sister's biggest advocate and champion. As part of their sibling and developmental support, CCLSs helped the boys indirectly engage in the process by decorating their sister's room and putting stickers on her mask. From a parental perspective, McCullough felt relieved because CCLSs served as a second voice and extra help for her. They reassured and validated to her kids what was going on through honest and accurate communication in a language McCullough's children could understand.

Find more information on supporting siblings in our article Supporting Siblings of Kids with Disabilities.

Accessing Child Life services

McCullough has never received a separate bill for Child Life services. However, if you have private insurance, it is always wise to contact your health insurance plan and check the benefits if you have concerns about whether Child Life is a covered service.

While Child Life services are extremely beneficial to patients and families, there is a work burnout and CCLS shortage. This means you may not have access to working with one, since there are more children in hospitals than there are child life specialists.

Virtual support

If your hospital doesn’t have a Child Life program, there are virtual options out there, such as Child Life On Call, who have specialists who can meet with your family virtually. Check with your hospital, healthcare system, or organization to see if they are a partner. If they are, services are free for families.

Taylor says, "While an app or a resource or a PDF or any kind of virtual support can't replace what an in-person child life specialist does, it does provide another asset that the family can have as a resource when Child Life can't be present. So there are about 6,000, maybe a little more, child life specialists in the US. And as an example, 30 million kids are seen in the ER each year. So there are just more children and families than there are child life specialists. And technology is a great way for us to bridge some of our resources."

When to ask for a child life specialist

Planning ahead

If you know you will be in the hospital, Taylor suggests always communicating your needs with a nurse. She says, "If you're in the hospital, if you're planning something scheduled, you can ask, especially if it's at a children's hospital, 'Can you please have a child life specialist call me ahead of time or child life specialists meet us when we get there?'" Often, a child life specialist will be assigned if one is available.

During the visit with families, Delano teaches parents to advocate for their child if she is unavailable. "When I work with families," Delano says. "I model my skill set so they can duplicate it in the future without me being present."

When you need support, any time

McCullough says to ask for a CCLS no matter how small the need may be. Since many families don’t know how a child life program can help, they don’t ask for one. Some aren’t aware that such a program exists, and unfortunately, not all hospitals will tell you about the service. McCullough also says when families are asked if they need help, some politely decline, stating: "It's just an IV; we brought our tablets." But what McCullough wants families to know is that your child's needs are just as valid and important as other families, and that requesting a CCLS doesn't take away from someone else who might need one, too. Most facilities offer a Child Life program.

Katherine Lauer also says to always ask for Child Life whenever you can: “They're so helpful. They're there to help. Child Life really will get to know your child and do what that child needs. So like, in our case, I think most children prefer distraction. So Child Life comes in armed with iPads that they physically put up in the child's face, to block them from seeing the IV or whatever scary things happen or the blood. And that's fine. And most kids would like that. Thomas [Katherine’s son] is what Child Life calls a watcher. He always wanted to watch. And he would physically shove away iPads — ‘Get that out of my face’ — [so he could] see what's going on. And he would ask me endless questions. And Child Life responded to that and respected it. And they would tell him what every minutiae of the tools were called, and how it worked, and what it was doing with his body. He just wanted to talk about all of it. And that helped him feel in control and like he was safe. And I love that Child Life met him where he was.”

Author