Sensory Processing Disorder and Sensory Diets

Does your child bristle or flat-out melt down in response to bright light, loud noises, or certain smells? Do they struggle to identify when they are hungry, are tired, or have to go to the bathroom? Do they have an uncontrollable case of the wiggles?

If you answered yes to any of these questions, your child might have sensory processing issues, sometimes known as sensory processing disorder. To learn more about sensory processing difficulties and common interventions, we spoke with LA-based developmental-behavioral pediatrician Dr. Josh Mandelberg, FAAP; TheraPlay LA founder and CEO Dr. Marielly Mitchell, OTD, OTR/L, SIPT, SWC; Abundance Therapies founder and director Kelli Smith, MS OTR/L; and educational advocate and Know IEPs founder Dr. Sarah Pelangka.

What is sensory processing disorder?

Sensory processing issues affect somewhere between 5 and 16% of Americans. Because of developmental differences in their brains, people with sensory processing issues struggle to self-regulate their sensory systems, especially when they’re feeling overstimulated or understimulated by their environment.

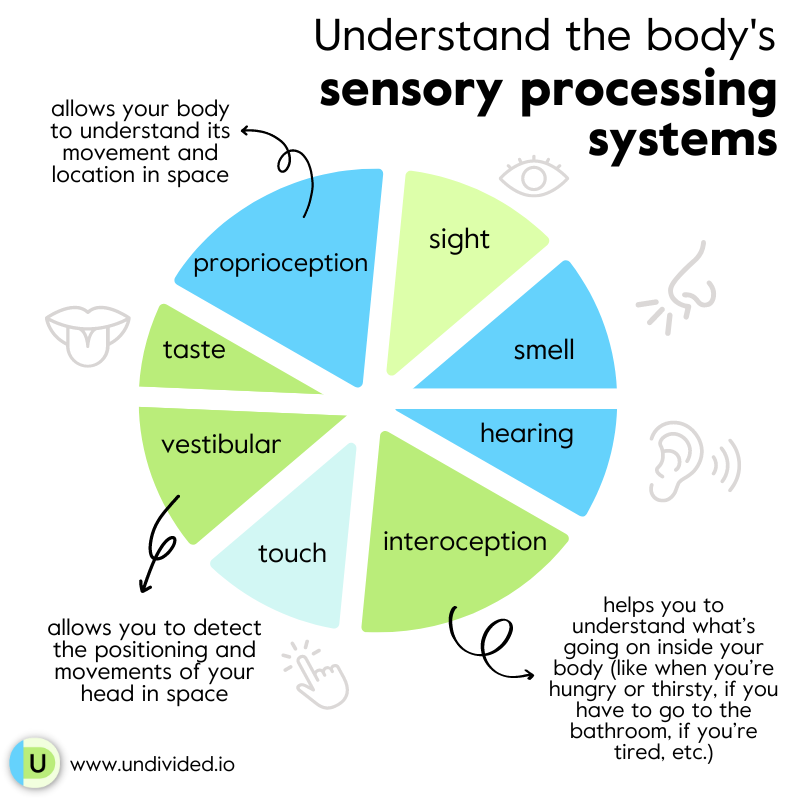

To understand sensory processing difficulties and why clinicians treat this condition the way they do, it’s critical to first understand the body’s sensory processing systems. You’re probably familiar with the five senses — sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch — but there are actually eight. The three lesser-known senses include proprioception, which allows your body to understand its movement and location in space; vestibular, which allows you to detect the positioning and movements of your head in space; and interoception, which helps you to understand and feel what’s going on inside your body (like knowing when you’re hungry or thirsty, if you have to go to the bathroom, if you’re tired, etc.). Some people with sensory processing issues experience difficulties with all their sensory systems to varying degrees, while others may only experience difficulties in one or two.

“If we have a signal going off in one of these sensory centers that's sort of uncomfortable and spreading negative vibes, that's going to bleed into a lot of other parts of our brain and can distract us, dysregulate us, scare us, or just sort of overwhelm us in different ways,” Dr. Mandelberg says.

Signs, symptoms, and causes of sensory processing issues

Every human is born with a unique sensory profile. Some of us might experience sensory issues when we’re younger but grow out of them as our brains mature and develop, Dr. Mandelberg and Dr. Marielly concur. That means a child exhibiting sensory difficulties at age 2 won’t necessarily present with them forever. But in people with sensory processing disorder, that isn’t the case — they continue to exhibit sensory-seeking or sensory-avoiding behaviors for the rest of their lives. (That doesn’t mean treatment for sensory processing issues isn’t possible, though! We’ll explore treatment options in more depth later in this article.)

Typically, children with sensory issues are either hyporesponsive or hyperresponsive to sensory stimuli, though it’s possible to be both, Dr. Marielly says.

Children who are hyporesponsive are less reactive to sensory stimuli than their typically developing peers, and they tend to be sensory-seeking to fill the gap of what they’re missing.

Children who are hyperresponsive are more reactive to sensory stimuli than their peers, and they tend to be sensory-avoiding because they’re bombarded with stimuli and want to pull away.

Sensory processing symptoms exist on a spectrum, and no one person experiences or responds to them in the same way. Depending on the intensity of your child’s sensory challenges and co-occurring conditions, they could present with milder or more severe sensory-seeking and/or sensory-avoiding behaviors. A child with less severe sensory issues might be able to mask their discomfort in response to certain sensory stimuli, while another with more severe sensory issues might react by hitting themselves, screaming, biting, or smearing feces.

However your child responds to sensory processing difficulties, it’s important to view their behaviors as a form of communication, Dr. Marielly says. She elaborates in the video below:

Signs your child might be hyperresponsive, or sensory-avoiding, include:

- Becoming easily overwhelmed or scared by certain sensory input (sounds, smells, textures, noises, or visuals); reacting to sensory stimuli in a manner most people wouldn’t (such as screaming, running away, or harming themselves or others)

- Actively avoiding certain sensory stimuli (for example, touches, hugs, kisses, hand-holding, loud music, scented candles, rough play, etc.)

- “Picky” eating

- Experiencing aversion to personal grooming practices (such as bathing, brushing teeth, or washing face)

- Experiencing aversion to bright lights

- Experiencing aversion to certain clothing textures and features (such as microfiber, fleece, bulky seams, or tags); preferring smooth, silky fabrics and looser-fitting garments; removing clothing or undergarments when they shouldn’t

- Preferring quiet, calm environments

- Using specific routines and items to calm down after encountering overwhelming sensory stimuli (for example, rewatching a favorite TV show or movie, playing a favorite game, reading a favorite book, wearing a specific type of fabric, or snuggling with a comfort item like a blanket or stuffed animal)

Signs your child might be hyporesponsive, or sensory-seeking, include:

- Having an unusually strong desire to touch/feel things and people

- Talking too loudly or too softly and not realizing it

- Not knowing their own strength; not understanding personal space

- Not understanding social cues; exhibiting disruptive behaviors in social settings (such as leaving their seat in class when they shouldn’t or being unable to sit still at their desk)

- Experiencing oral fixation (such as chewing on hair or sucking on their thumb); putting non-food items into the mouth

- Squeezing the body into tight spaces (like between furniture)

- Sensory “stimming,” such as flapping the arms/hands, spinning, rocking in place, or making noises

- Preferring heavy hugs and deep pressure

- Appearing clumsy, disengaged, or aloof

- Underreacting to sensory stimuli that would bother most people (including pain)

- Thrill-seeking

- Exhibiting self-injurious behavior when understimulated (such as skin-picking or nail-biting)

- Having lots of energy and struggling to calm down when necessary or beneficial

Some universal signs related to sensory processing issues (regardless of whether your child seeks and/or avoids sensory input) include:

- Poor sleeping habits (such as bed-wetting, requiring you to be in the room or next to them in bed while they fall asleep, taking an unusually long time to fall asleep or wind down for bedtime, tossing and turning, sleeping less than eight hours a night regularly, or waking in the night after they’ve already fallen asleep)

- Mouth breathing (Dr. Marielly says breathing through the mouth as opposed to through the nose causes baseline nervous system dysregulation, which leads to sensory processing issues; mouth breathing can also be caused by medical issues such as sleep apnea and deviated septum)

- Fine motor skill difficulties (such as struggling to grip a pencil, messy eating and drinking, or poor coordination)

- Delayed communication and social skills

- Low or high muscle tone, poor posture

- Mood swings and tantrums

While the exact cause of sensory processing issues isn’t known, researchers have found that genetic, prenatal, and postnatal factors contribute to its development. “Your sensory experiences through utero and your infancy really do have an impact on the way that your [sensory] profile develops — some kids just pop out needing certain kinds of sensory input,” Dr. Marielly says. She elaborates in the video below:

Sensory processing disorder as a diagnosis

Despite the prevalence of sensory processing difficulties across various diagnoses, sensory processing disorder is not formally defined by or included in the most current iteration of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5, which physicians use to diagnose psychiatric and developmental conditions. There is debate in the medical community over whether sensory processing issues should be a distinct diagnosis in the DSM — some doctors say yes, while others believe sensory processing issues should be considered symptoms of the diagnoses they tend to present in most: autism, ADHD, OCD, Down syndrome, and other developmental conditions. They can coexist with conditions involving motor and musculoskeletal issues, Dr. Mandelberg says.

While sensory processing issues are defined as a symptom of autism in the DSM-5, in Dr. Mandelberg’s clinical experience, they do not occur solely in people with autism. “I think [sensory processing issues] are a more general reflection of immaturity in the brain. … It’s not only seen in autism; it’s just something that can go along with it,” he tells us.

Defining sensory processing difficulties in the DSM could lead to a better understanding of the condition as a whole, Dr. Mandelberg says. “One of the benefits of having things defined more specifically [in the DSM] means that we can do research on them … Being able to at some point have a more specific formal diagnosis could hopefully serve our understanding of it better in time.”

How and when are sensory processing issues assessed and treated?

Because sensory processing disorder isn’t recognized by the DSM, it’s not a condition that can be formally diagnosed by a clinician. That doesn’t mean it can’t be treated, though.

When considering treatment, it’s important to look beyond an individual’s sensory issues and behaviors alone — they’re only part of the puzzle, Dr. Marielly says. “Are they breathing well? Are they sleeping well? Are they pooping well? And are they eating well?” She elaborates on how physical health issues can affect sensory processing in the video below:

Children whose sensory processing issues are more visible to others and who have co-occurring disabilities are more likely to be flagged by their school for special education testing via an IEP assessment, while others will fly under the radar because they’re able to mask their sensory discomfort. (This is especially true for girls with autism.) Because of this disparity, it’s important to advocate for your child if you think they might be struggling with sensory difficulties.

If your child doesn’t already have an IEP, the first step to accessing treatment for sensory issues and other potential conditions is requesting an IEP assessment from their school. (Learn more about the process in our article IEP Assessments 101.) Let the assessors, especially the school occupational therapist, know that you believe your child might have sensory processing difficulties. If your child already has an IEP and you would like their team to evaluate and accommodate them for sensory processing difficulties, request to schedule an IEP meeting so that you can discuss your concerns.

Outside of school, you can look to your child’s healthcare providers for assessment and treatment. Dr. Mandelberg recommends bringing your concerns up with your child’s general pediatrician to discuss and see whether they have ideas to help with these sensory difficulties. If their efforts are ineffective or they determine your child’s sensory issues to be more severe, they might refer you to visit a developmental-behavioral pediatrician, like Dr. Mandelberg, or an occupational therapist, like Dr. Marielly. Treatment typically includes occupational therapy, sensory integration therapy, and sensory diets (more on that below).

Dr. Marielly recommends finding an occupational therapist with additional sensory processing training, as they will be the most qualified to develop an effective treatment plan.

Find an occupational therapist (OT)

Sensory diets 101

Sensory issues, regardless of their cause or nature, can make it extremely uncomfortable for kiddos living with these issues to navigate the world. A well-designed sensory diet can help alleviate that discomfort.

What is a sensory diet?

A sensory diet is a set of compensatory strategies and activities created by an occupational therapist to help a child better cope with sensory processing difficulties, according to Dr. Marielly. “It’s like food for the nervous system to help it operate better,” she says.

“The real idea behind the sensory diet is self-regulation and to find that just-right place for our children [sensorily] so they can actually function,” occupational therapist Kelli Smith says.“It’s really to help our children understand why they may like something or not like something.”

Some sensory diets take the form of a daily schedule of preplanned activities to regulate the nervous system, while others operate more as a toolbox of ideas to draw from on an as-needed basis. A structured sensory diet with scheduled activities could resemble this example from Senso Minds:

Xavier is 9 years old. He has a diagnosis of autism. He wakes up and is immediately “off the walls” seeking input. He might benefit from deep proprioceptive input right away and every 1-2 hours after that to keep him modulated throughout the day.

8 a.m. he jumps on his trampoline.

10 a.m. he crashes into the couch pillows.

12 p.m. he blows up 4 balloons.

2 p.m. he has a thick smoothie through a straw.

4 p.m. he reads a book under a weighted blanket.

6 p.m. he has some crunchy carrots with dinner.

8 p.m. he listens to calming music while watching a lava lamp in a room with calming essential oil.

Just remember, if tomorrow he wakes up and is cranky and irritable (while bouncing “off the walls”) his sensory diet activities could possibly need to be totally different.

Examples of activities that could be included in a sensory diet

- Wearing noise-canceling headphones when overstimulated by sound

- Wearing compression and/or weighted clothing to reduce physical anxiety from sensory overwhelm

- Taking time to sit under a weighted blanket or lap pad to reduce sensory overwhelm

- Creating a dedicated safe space in your home where your child can go when they need to self-regulate; wrapping your child tightly in a blanket or towel before bed to help them calm down and prepare for sleep

- Engaging in physical activity in the morning before school to thwart sensory-seeking behaviors while in the classroom (for example, swimming, dancing, jumping, or walking/riding a bike to school)

- Keeping fidget toys on hand for your child to play with when they are understimulated

- Doing “heavy work,” like pushing the chairs around in the classroom before class starts or carrying a full laundry basket from one room to another

- Swinging after school for five minutes before driving home

- Jumping on a trampoline for 10 minutes when your child seems to need stimulation

- Brushing teeth with a vibrating toothbrush

- Crab walking

- Blowing up balloons

- Finger painting

- Scheduling meals with foods that cater to your child’s sensory needs (like crunchy foods for sensory seekers or “safe” foods for sensory avoiders)

- Listening to music before bed and/or after waking up

- Using aromatherapy at targeted times of the day

- Doing yoga before bedtime for 15 minutes to wind down

- Taking a bath with essential oils to prepare for bedtime

How your child’s sensory diet will look depends on their specific sensory profile (sensory-seeking and/or sensory-avoiding) and the severity of their behaviors in response to sensory discomfort. Dr. Marielly and OT Smith say it’s difficult to detail general examples of sensory diets because every child’s health circumstances and needs are so unique.

“Everybody wants a universal method or suggestion [for sensory diets], but … that's just not how the nervous system works. That's not how people work,” Dr. Marielly says. “You have to think really critically and see what that nervous system is communicating and what it wants, and then make those recommendations accordingly.”

The sensory diet creation process

Before your child’s occupational therapist can start drafting an effective sensory diet, they first need to determine your child’s unique sensory profile. Is your child sensory-seeking, sensory-avoiding, or both? Are they under-responsive to sensory input? What type of sensory input do they seek out or avoid? Your child’s therapist will explore these critical questions when identifying their sensory profile.

Smith says that when she assesses a child’s sensory profile, she typically likes to observe them in school, at home,at the clinic, and in outdoor settings. Standardized testing and talking with parents about their own observations of their child in different environments are essential parts of this process as well, Dr. Marielly says.

Once the occupational therapist has developed a solid understanding of your child’s sensory profile, they will draft a sensory diet based on the information gathered during appointments and standardized testing. “Humans are onions with lots of layers,” Dr. Marielly says, and our sensory needs are constantly evolving, so don’t be surprised if your child’s therapist recommends amending the sensory diet occasionally. And just because a sensory coping skill doesn’t work for your child at one point in their life, that doesn’t mean it won’t at another, Smith explains in the video below.

How to incorporate a sensory diet at school: IEP and 504 accommodations for sensory processing issues

Like any other accommodation, a sensory diet should be incorporated into an IEP if your school district’s occupational therapist deems it necessary for your child to access their education, Dr. Pelangka says. It should be included in the Accommodations and Supplementary Aids and Supports sections of the IEP, and your child’s school should purchase any products required to carry out the diet — not you.

Because occupational therapists tend to “trial” sensory diets in real time and amend them as they learn more about your child’s sensory profile, they usually avoid writing specific sensory diet recommendations into the IEP, Dr. Pelganka says. Because of this fluidity, it’s vital to ensure the most current iteration of your child’s sensory diet is always attached to the IEP. If your child sees an occupational therapist outside of school, you can ask the school OT to consult with the private therapist for additional insight when developing the sensory diet.

A sensory diet can also be included in a 504 plan as an accommodation, Dr. Pelangka says. She advises parents to ensure that a current copy of the sensory diet is always attached to the 504 plan, just as she recommends with IEPs.

To ensure your child’s school is actually implementing their sensory diet, Dr. Pelangka recommends taking a proactive approach: “Ask for a copy [of the IEP or 504 plan with the sensory diet attached], conduct observations or send a blind observer to conduct observations, ask for pictures and videos to be sent on behalf of the staff. … Depending on what the diet consists of, they can also send some items home with the family for the student to use when doing homework, for example.”

If your child’s school says they cannot support a sensory diet as an accommodation in their IEP or 504, it’s because their IEP assessment team doesn’t feel it’s necessary for your student to access a free and appropriate public education. If you disagree with the school’s evaluation, speak up during the IEP meeting and ask for your objection to be documented in the narrative or parent notes, Dr. Pelganka says. If you cannot resolve the issue during the meeting, you have the right to ask for an Independent Educational Evaluation. If the school is not responsive, you can try alternative dispute resolution or mediation with your child’s IEP team. If those avenues do not bring about any change, you have the right to file a due process complaint and have your case heard by an administrative law judge.

What about sensory rooms?

The school environment is often filled with activity and noise, and can sometimes feel overwhelming for children with sensory issues. Enter sensory rooms - a sensory-focused space mean to support the unique needs of each student. There may even be one in your child's school!

Katie Krcal (MSOT, OTR/L) from Kidspace tells us, "Sensory rooms can be beneficial for children who have difficulty with sensory processing. They can help children take a break from feelings of overwhelm, help children regulate when seeking more sensory input, or both! For this reason, it is important to consult with your child's therapy team when building a sensory room. Depending on your child's specific needs, the room can contain tunnels, tents, trampolines, swings, crash pillows and more! The opportunities are endless."

Stay tuned for our upcoming article all about sensory rooms at school and how they can benefit our kiddos!

Sensory diets and supporting sensory processing difficulties at home

To best understand how you can help your child use their sensory diet at home, curiosity is key, Smith and Dr. Marielly concur. Ask your child’s occupational therapist to break down your child’s sensory profile, what each sensory diet activity seeks to accomplish, and why they prescribed it. If you don’t understand their explanation, ask them to clarify — understanding your child’s sensory needs is critical to effectively accommodating them in any setting.

You can also read books and research articles, listen to podcasts, and refer to occupational therapists’ social media accounts and blogs. Dr. Marielly recommends reading Jane Ayre’s book Sensory Integration and the Child and checking out the blog Pink Oatmeal.

Smith says, “It’s our job as adults to be able to give our children the richest exposure to all kinds of [sensory] elements and then kind of see, oh wow, what do they veer away from, and what are they driven towards, and how do those help?”

It’s also important to help your child understand their sensory profile and sensory diet so they can self-advocate for their sensory needs, accommodations, and boundaries when you’re not around. “It’s a life skill,” Dr. Marielly says. To help your child feel validated in their sensory experiences and boundaries, acknowledge when you notice your child is feeling overwhelmed or underwhelmed by their environment, Smith adds. “[Feed] that back to them, like, ‘Oh, yeah, you’re right. I heard that, too. That was really loud. That was a fire engine.’”

Be sure to keep track of how effective the sensory diet activities seem to be at reducing your child’s sensory discomfort. Consider documenting your observations in a diary and sharing it with your child’s occupational therapist — they can use the information to revise the sensory diet activities if they find it necessary.

“You want to see an adaptive response,” Dr. Marielly says. “So that might be improved posture when the child's on the swing, sustained eye contact, random vocalizations, improved catching or throwing while playing with a beanbag … it could be so many things depending on what that little person is supposed to be doing and where they're at.”

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor