Down Syndrome 101

3 key takeaways

- Down syndrome is a genetic condition caused by the presence of an extra 21st chromosome, which affects development.

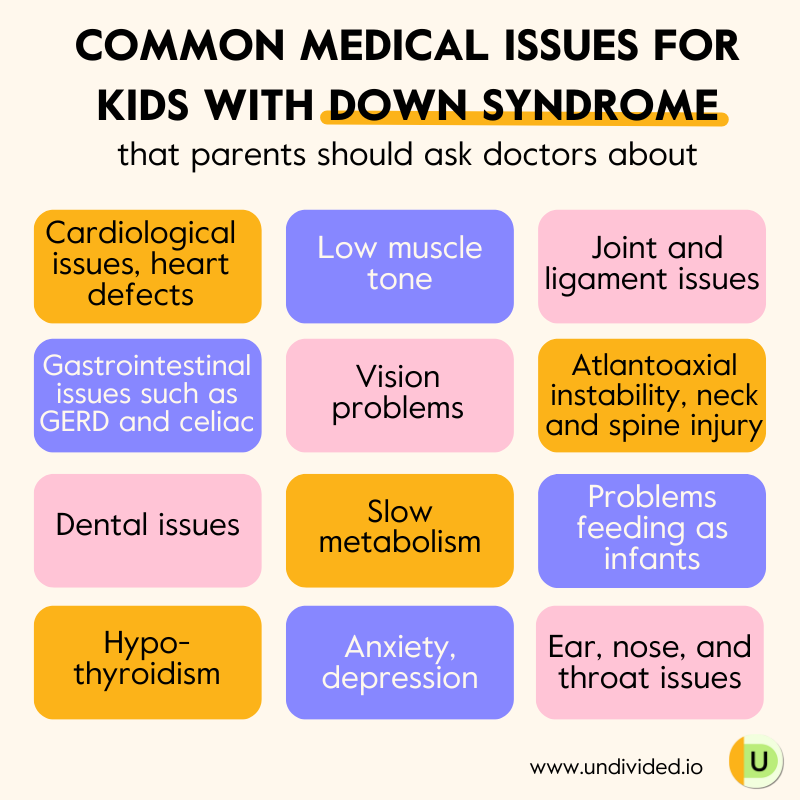

- Common medical concerns for kids with Down syndrome include low muscle tone, gastrointestinal issues, vision issues, and hypothyroidism, among others, which can be treated.

- Developmental concerns may include co-occurring autism or intellectual disability, motor delays, speech delays, and behavior challenges, but every individual is different.

Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal condition. A third copy of the 21st chromosome has multiple effects on physical and intellectual development, but increasingly, people with Down syndrome are thriving and living longer and even enviable lives.

Many parents today discover their child has Down syndrome before they meet them, based on the results of noninvasive prenatal screenings or prenatal diagnostic tests. Others will receive a diagnosis after birth (confirmed by a karyotype test run after the baby is born), but for the most part, babies with Down syndrome are identified very early, providing an opportunity to make the most out of early intervention.

In this article, we will set out what medical, developmental, and social issues parents can expect for their child and suggestions for where parents can find available supports. To gain expert insight into what families need, Undivided talked to Nancy Litteken, executive director of Club 21 Learning and Resource Center in Pasadena, and Emily Mondschein, executive director of Gigi’s Playhouse in Buffalo, New York, both of whom are also parents of individuals with Down syndrome.

A note about language: Within the US, the Down syndrome community prefers to use the term “Down syndrome.” In the UK, “Down’s syndrome” is the preferred term. While it is common to use the abbreviation DS or T21, using “Downs” on its own can be offensive. There is also a strong preference for person-first language, i.e., “a child with Down syndrome.” While the medical community might refer to the condition as a “defect” or refer to individuals “suffering” from Down syndrome, within the Down syndrome community these labels are frequently protested. Down syndrome is a condition or a syndrome, not a disease. People “have” Down syndrome, they do not “suffer from” it and are not “afflicted by” it.

What is Down syndrome?

Down syndrome is a genetic condition, although it is not usually inherited. According to the most recent data, about 5,100 babies every year are born with Down syndrome, which is about 1 in every 772 babies. A study in 2016 estimated that about 1 out of every 1,490 people living in the United States have Down syndrome, approximately 217,163 individuals. Down syndrome occurs in all races. And while older mothers are indeed more likely to have a child with Down syndrome, due to the higher birth rate among younger mothers, most babies with Down syndrome are actually born to young mothers.

Down syndrome was first identified by Dr. John Langdon Down in London in 1862 when he identified a group of patients with similar symptoms and facial features. Later, in 1958, Jérôme Lejeune discovered that Down syndrome was caused by the presence of an extra 21st chromosome. The additional copy of that chromosome is a natural phenomenon that occurs during the normal process of the duplication of cells.

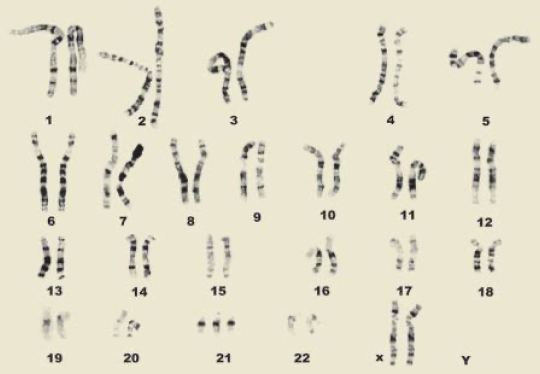

Image sourced from National Down Syndrome Society.

Image sourced from National Down Syndrome Society.

Most people have 23 pairs of chromosomes in each cell; these chromosomes determine the person’s growth and development throughout their life. The extra 21st chromosome means that individuals with Down syndrome have 47 chromosomes. Individuals with 47 chromosomes usually have trisomy 21 — by far the most common type of Down syndrome, accounting for about 95% of cases. However, around 3% of people with Down syndrome have translocation Down syndrome, in which the third copy of the 21st chromosome is attached to another chromosome — in other words, there is a chromosomal rearrangement along with the presence of an extra chromosome. Translocation is the only type of Down syndrome that may be hereditary; however, not all cases of translocation Down syndrome are inherited. The remaining 2% of people with Down syndrome have mosaic Down syndrome, in which only some cells have an extra copy of the 21st chromosome. Like trisomy 21, mosaic Down syndrome is not inherited.

Knowing which type of Down syndrome your child has does not predict that child’s future outcomes. Like all people, individuals with Down syndrome develop uniquely, with both strengths and weaknesses. However, knowing whether your child has translocation can give you an idea of the chances of having another child with DS. Many families consult with a genetic counselor as part of receiving their child’s diagnosis. You can read more about prenatal testing in this guidebook by The Global Down Syndrome Foundation.

How is Down syndrome diagnosed?

Karotype testing

A small blood sample is required to create a karyotype: a laboratory-produced image of a person's chromosomes isolated from an individual cell and arranged in numerical order. The karyotype will show definitively whether a child has Down syndrome.

Karyotype results are not available immediately, but Down syndrome may be suspected at birth if a baby has certain markers, including low muscle tone (the baby will feel “floppy” compared to a typical baby), a single palmar crease, certain distinctive facial features (a round face, small jaw, almond-shaped eyes, flat nasal bridge, and low-set ears). If you or your baby’s medical team suspect Down syndrome, the team should run a karyotype test to confirm.

Cell-free DNA screening

Non-invasive prenatal screening (NIPS), also known as cell-free fetal DNA screening, has been available since 2011 to assess the risk of a pregnant woman’s developing fetus having a chromosome disorder, such as Down syndrome. NIPS uses cell-free fetal DNA sequences isolated from a maternal blood sample test. Studies show about 99% accuracy in such tests, but NIPS isn’t a diagnostic test; an actual diagnosis must still be confirmed by a prenatal diagnostic test, such as an amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling, or by a karyotype test run after the baby is born. Many parents choose to forego the prenatal diagnostic tests and wait until the baby is born for confirmation, given the relative accuracy of screenings and the very slight possibility of complications as a result of prenatal diagnostic tests.

After a new diagnosis

Receiving a new diagnosis is a lot to process, accept, and understand. Nancy Litteken tells us about the impact of the diagnosis on parents and how providers often deliver the diagnosis by saying “I'm sorry,” which she is committed to changing. When new families come to Club 21, Litteken says, “The first thing we say is congratulations. We say how beautiful this baby is because truly, and in our office, people are oohing and aahing. You kind of need that oohing and aahing because sometimes you're afraid to go to the store, like I was, to see what somebody would notice or what your friends will say. And so I think it's important to have oohs and ahhs and congratulations and whistles blown and all that.”

She continues, “This diagnosis leads us to fear, and I think fear blinds us, and every single one of us comes to that diagnosis with some kind of little suitcase with all our assumptions and all our knowledge…. I think fear, with any disability, is the thing that kind of crops up.”

But, with any diagnosis, Litteken reiterates the importance of processing grief: “For new parents, I do not want to minimize the loss that a diagnosis brings and also what fear brings. There's so many possibilities, but I want new parents to say, ‘Give me space to feel the feelings.’” She suggests seeing a therapist or doing grief work to explore and feel all the feelings. “I think there's a phrase that says don't pitch your tent in the valley of sorrow, and I think, ‘All right, feel the feelings, feel the sadness, know that there'll be another round, another place where you do feel sad. But just keep moving.’”

Some babies with Down syndrome will spend time in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), even if they were born full term, due to heart, lung, or gastrointestinal issues. A NICU stay can be very stressful for parents. If your child is facing one, you will need support from family and friends. As much as you can, focus on self-care. And while you are a key part of your child's care team, and your input and participation is important, it’s also okay to let the nurses do their job. You can even find out which nurses you and your family work best with and how to request them specifically for future visits. This is a great time for you and your extended family to learn more about Down syndrome. When the baby is ready to move to less intensive support, the staff will show you how to take care of your baby's unique needs.

Obtain a diagnosis for my child

Common medical issues in individuals with Down syndrome

Your child may or may not have many of the issues present on the long list of “symptoms.” Common issues include:

- Cardiological Issues: About half of children with Down syndrome are born with a congenital heart defect. The National Down Syndrome Society (NDSS) lists some of the most common ones. Most heart defects related to Down syndrome can be surgically corrected.

- Low muscle tone (hypotonia), loose ligaments, and joint instability: Nearly all children with Down syndrome have some or all of these musculoskeletal effects, which generally delay common childhood milestones, such as head stability, sitting up, crawling, walking, and even talking. Muscle tone can also result in fatigue, though the tone can improve over the individual’s lifetime.

- Gastrointestinal issues: At birth, there may be GI abnormalities, such as Hirschsprung disease or duodenal atresia, that can be corrected with surgery. These are not terribly common, but they are more common in babies with Down syndrome than in typically developing babies. Children with DS are also at a greater risk for reflux (GERD) and celiac disease. Children with DS also may have chronic constipation due to low muscle tone.

- Ear, nose, and throat issues: Chronic ear infections, middle ear effusions with associated hearing loss, obstructive sleep apnea, and chronic rhinitis and sinusitis can all be common in individuals with Down syndrome.

- Vision issues: Many individuals with Down syndrome will have vision problems at some point in their life. Most issues can be resolved with glasses, and older children often are able to wear contact lenses.

- Atlantoaxial instability: Vertebrae in the neck may be misaligned, putting some children with Down syndrome at risk of serious injury to the spinal cord from overextension of the neck. This, too, is not a terribly common condition, but parents should be aware of it and screen for it if recommended.

- Dental issues: Malocclusion, misaligned teeth, periodontal disease, and cavities can all occur in people with Down syndrome..

- Nutrition: Individuals with Down syndrome typically have a slow metabolism. Babies and young children are often underweight due to feeding issues, but older children and adults are 60% more likely to be obese. Families are encouraged to focus on nutrition and hydration.

- Thyroid: Many individuals with Down syndrome have hypothyroidism. This can contribute to obesity, mood swings, depression, and further cognitive delay. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that children with Down syndrome have yearly blood tests to check for hypothyroidism.

- Mental health: Despite the common myth, adolescents and adults with Down syndrome are not “always happy.” Just like people in the general population, they can develop anxiety and depression and may need specialized mental health support.

Looking at this list can be daunting, but it’s important to remember that a child with Down syndrome may have only a few of these issues, and the majority of them are very treatable or manageable.

Parents may occasionally experience medical professionals who dismiss a health concern by saying, “It just comes with Down syndrome.” That is no reason not to treat the medical issue, but it is a reason to consider changing doctors. Parents should be proactive in sharing the AAP’s Health Care guidelines for children and adolescents with their pediatrician. It’s a great guide that can help you prioritize what to discuss with your child’s primary care provider during the different age ranges. You can use the above list and the AAP guideline as a guide to topics and questions you might want to ask your pediatrician or primary care provider.

Why learn about common medical issues?

Emily Mondschein tells us, “First and foremost, it's important to understand the medical impact of the extra 21st chromosome on development. I think a lot of times we mistake things in this population as other things because we don't understand that this child is acting out and they have a behavior issue, but we haven't looked into the gut, we haven't checked out reflux. Another example: We think that there's something neurologically happening where the child is just exceptionally weak because they can't climb stairs, but perhaps they have depth perception issues because of their vision. So on the whole, there are just so many different pieces like this that have to do with trisomy 21 that impact the body. So I think sometimes, if parents aren't educated on that, they're flying blind a bit.”

As the parent of a child with Down syndrome, it’s important to be informed about the health concerns that can be present. Unless you live close to a Down syndrome medical center, such as RADY, CHOC, Charlie’s Clinic in Oakland, the Center for Down Syndrome at Stanford, the Sie Center in Denver, or Mass General in Boston, you may not find a doctor with specific expertise in Down syndrome.

In addition to your child’s pediatrician, your medical team may also include a developmental pediatrician and specialists such as a cardiologist, an endocrinologist, a neuropsychologist, a speech pathologist, an occupational therapist, a physical therapist, an audiologist, and more. Many children with Down syndrome are quite healthy and do not require many visits to specialists, but if you do need them, they’re a good addition to your child’s care team. Hospital Social Workers can be an excellent resource to help coordinate various members of the healthcare team after discharge.

Build my child's care team

Common developmental issues

Common co-occurring conditions and developmental concerns for families to be aware of include:

- Intellectual disability

- Autism and ADHD

- Feeding challenges

- Speech and language delays

- Motor development delays

- Behavior challenges

To learn more about each of these in relation to Down syndrome as well as the recommended therapeutic interventions, check out our full article Common Down Syndrome Therapies and Specialists.

Overcoming stereotypes

Stereotypes about Down syndrome have been floating around for decades. Some of these myths can be quite negative, such as that children with Down syndrome will reach a plateau in their ability to learn. Other misconceptions sound positive but can be equally damaging, such as the assumption that people with DS are always happy, which sets an unrealistic standard for a person to live up to. There is no evidence to support these myths and plenty of evidence to the contrary.

Litteken explains that parents need a mindset that people with Down syndrome are important in this world, that they belong, and that they can do amazing and hard things. “You emphasize and notice what gives them joy, notice what they can contribute to the world.” A growth mindset is also important: “Everyone in life struggles. It's really important to teach the concept of ‘not yet.’ You can't do this yet, but you will.“

What do parents of children with Down syndrome need?

We asked Litteken and Mondschein about the most important things that parents of children with Down syndrome need. Here’s what they shared:

Community

By far the best part of having a child with such a common disability is the wonderful local, national, and global community of families. Litteken tells us that it’s important that parents have a community because you need people a little ahead who can support you. You can also support “people behind you that have a baby and you can say, ‘Don't worry, you know what, I have the best lactation specialist. Look, we're gonna get you started.’ We have lots of programs, and there are programs all over, but I would encourage people to always be plugged into a program. There are seasons when your other child needs you more. There are seasons when your parents need you more. But I think staying connected to a solid group of a program — Club 21, or one that you choose — eases the stress. You know someone has your back.”

You can find a local Down Syndrome Association or a Gigi’s Playhouse to find other Down syndrome families. Nationally, the National Down Syndrome Congress has an annual convention. Down Syndrome International brings together families from all over the world with global projects and events. There are many Down syndrome–focused Facebook groups as well — some local, some national, and some international. See our list of national and local Down syndrome support organizations to find other helpful resources.

The community is also brought together by awareness events celebrated around the world. On March 21 each year (3/21), World Down Syndrome Day is marked by a special session at the UN and many local meetups, as well as online celebrations and videos. In the United States, October is recognized as Down Syndrome Awareness Month. Many local organizations have walks to raise money and awareness.

Love, patience, acceptance, and self-care

Litteken tells us, “I think doing this alone is really stressful and lonely. So there might be seasons you go away. Then you just walk back in and you don't make apologies, you just say, ‘I have a lot going on in my life. And I'm back.’”

Mondschein agrees, telling us that parents often put themselves on the back burner. In this clip, she explains how parents can show up positively, and with love, for their kids and themselves:

Vision

Having a vision, dreaming of what you want for your child, and creating that vision as you go is very important. Litteken tells us, “I think you need to have a big vision because if you don't, with every roadblock that comes, you keep pointing back to [that big vision] and you say, ‘This is where I'm headed, does this match?’ And if you don't, you'll sometimes just say, ‘Oh, someone said he's not going to talk. I'll just accept it.’ And there is a difference between accepting something and being a detective that says, ‘I am going to figure out what's missing and why this isn't happening.’ Having that vision helps you be a fighter, a champion.”

An informed care team

Litteken tells us that it’s important to build a team of people who have the research-based, accurate information about Down syndrome: “Everyone will tell you what they know about Down syndrome — school teachers, administrators, doctors — and I promise you they don't all have the right information. I know that's almost sacrilege. Often they have outdated information, or they have it on a small population. So what you need is research and informed, accurate information on Down syndrome — not just disabilities, which might be helpful because you'll become an expert on all kinds of things. But you need someone who has information about Down syndrome. There are too many myths out there, and there's too much outdated information running around. I think research and good information is a game changer.”

Education on the next steps

Along with having an informed care team, you need to be informed as well. Litteken explains the importance of keeping ahead of your child’s development in your understanding of the potential needs that will likely come up.

What do siblings of people with Down syndrome need?

Siblings of a person with DS will likely have the longest relationship, and they need support too. Sibshops is an evidence-based program offering support to children and teens who have a sibling with intellectual or developmental disabilities. There are literally hundreds of Sibshops available worldwide.

Dr. Brian Skotko, director of the Down Syndrome Program at Massachusetts General Hospital, has a sister with Down syndrome and has dedicated his professional energy to children with developmental and cognitive disabilities. He has published research showing that most siblings of a person with DS have very positive feelings toward their sibling. Sibshop’s own research shows that many siblings pursue careers as professionals in the disability community because of their positive experience as a sibling.

That said, siblings are human and may sometimes experience feelings of jealousy and resentment due to the additional attention and resources that their sibling needs. It is helpful for siblings to have opportunities to express their feelings and gain peer support from other siblings in the community. In addition to Sibshops, Dr. Skotko has written a useful guide for older siblings.

What can I expect for my child with Down syndrome?

There is no real way to answer this question — just as every person has unique strengths and challenges, so does each person with Down syndrome. Many adults with Down syndrome can live independently with support, get married, have jobs, or own businesses.

Check out this series of videos featuring adults with Down syndrome answering questions, such as whether a person with Down syndrome can get their driver’s license.

It can be inspiring to think about achievers in the Down syndrome community, including:

- Pablo Piñeda, an actor who has earned a college degree

- The stars of Born this Way, many of whom have successful careers and live independently

- Kim Chandler, Special Olympics swimmer and swim instructor

- Madeline Stuart, model and inclusion advocate

- Lauren Potter, actress who starred in Glee, among other series

Not every person is destined to be a well-known achiever, and the same holds true for people with Down syndrome. Most parents of children with Down syndrome who are living quieter lives, out of the spotlight, will tell you that their lives are richer for having their child — regardless of what their child achieves. Ellen Stumbo, mother of a daughter with Down syndrome, wrote a poignant piece on this very subject.

For more information on Down syndrome, read The National Down Syndrome Congress’s Resources for New and Expectant Parents.

Be sure to also check out our article Supporting a Child with Down Syndrome at School for information about special education and IEPs specific to kids with DS.

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor