Expand Your Picky Eater’s Diet the OT Way

While almost every child (neurotypical and otherwise) goes through a phase where they’re very picky about what they’ll eat, some kids may need the additional support of feeding therapy to get the nutrition (and broader palate) they need as they grow. We talked with Laura Hogan-Reyes, MA, OTR/L, SWC, about how to help kids branch out to new foods and textures, and how to get more nutritious foods into a limited diet. Hogan-Reyes, a longtime co-owner of Pasadena’s Center for Developing Kids now working with kiddos 0–3 through Regional Center, has been an occupational therapist for 36 years and specializes in feeding therapy. We also asked autism dietician Brittyn Coleman, MS, RDN/LD, for her expert tips!

Picky eating vs. problem feeding

Hogan-Reyes tells us that over the past 10 to 12 years, there’s been a significant increase in extremely picky eaters, which is suspected to be tied to an increase in autism. She also says that 70 percent of children with autism have an atypical feeding pattern or limited intake. But it’s important to know what type of picky eater you have: “A lot of parents say their child is a picky eater, but there’s a difference between picky eating and problem feeding,” Hogan-Reyes says. “Picky eating is where you’d rather have your child be — they have thirty or more foods in their range. A problem feeder usually eats less than twenty foods.”

Depending on diagnosis, it’s important that parents seek out professional guidance to find out if their child is really a picky eater. Children with Down syndrome, for example, often have low muscle tone or generalized muscle weakness, which can affect their chewing strength. In this case, they are treated from a sensory and motor perspective. Some children also have swallowing issues, so you’ll want to rule out sensory, motor, or physical issues first.

Exposure/desensitization to foods

Hogan-Reyes says the first step in treatment is to give kids a solid starting point: “Rather than focusing on the goal of getting your child to try a new food, we need to give them a foundation first. I want these kids to tolerate being in the same room with a new food, where they can look at the food without throwing their plate off the table.” She explains that getting to a point where your child is visually tolerant of the new food is a big step. Smell is a big issue for some kids; if the food is merely in their presence, they can get the visual and olfactory sense of it. “We have to celebrate those successes,” Hogan-Reyes says. “Parents want them to eat it, but let’s give them some time.” You could also have them cover the food with plastic wrap and put it back in the fridge. Coleman says that some kids even start with looking at pictures or videos of the food on their phone.

Coleman reminds us that eating a new food is not the only win!

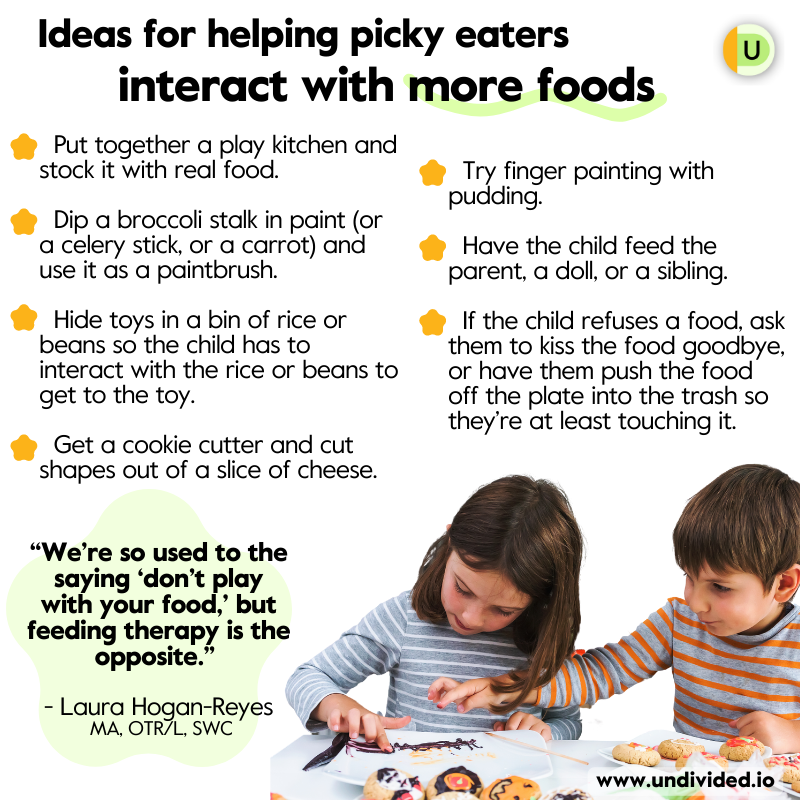

The next step is to have kids interact with the food. “We’re so used to the saying ‘don’t play with your food,’ but feeding therapy is the opposite,” Hogan-Reyes says. So go ahead — play with the food! Here are some great suggestions for how to start:

“By playing and having positive experiences with food, kids get that exposure and desensitization,” Hogan-Reyes says.

Food chaining

The second step of treatment is called food chaining — a technique where you chain together foods through the use of similar properties. “Let’s say that Mikey will eat French fries, but his parents want him to eat chicken; as a therapist, I have to find a characteristic of the preferred food and pair it with the nonpreferred food,” Hogan-Reyes says. “Trader Joe’s sells chips called Veggie Sticks (also called Veggie Straws elsewhere), which are great because there are three colors. The white ones look similar to a French fry (same color and shape), but it’s not the same texture. If we can get Mikey to eat that, maybe we can get him to try Burger King’s chicken fries.” She adds that if you can get a child to eat the orange veggie stick, maybe you can get them to try a carrot stick!

Listen to Coleman’s tips for taking inventory of what your child currently will eat and thinking about how to expand from there:

Presentation of food for kids

A good place to start is by taking a preferred food and changing up the visual presentation so you’re not always offering it in the same way. If grilled cheese sandwiches are a preferred food and you usually cut them into triangles, try cutting them into squares. “The child might refuse it at first because it seems like a new food, but if they can accept the different shape, it’s a win because they’re showing progress,” Hogan-Reyes says.

She adds that if you suspect your child is becoming picky, don’t let them see containers: “If you’ve been giving them Yoplait yogurt in the container and then try to give them a Dannon yogurt, in their mind it’s a completely different food.”

Deception techniques

This sounds devious, but it’s really just being a little sneaky. Hogan-Reyes says we should aim for kids to get some form of protein, dairy, vegetable, and fruit every day. “Vegetables seem to be the hardest for most kids, but there are many ways to sneak them in,” she says. Here are a few examples:

A lot of kids will accept fruit juices, and there’s more on the market now for combined fruit and vegetable juices; you can also try incrementally adding pureed vegetables or veggie juices into the preferred fruit juice.

If they like pancakes, add a miniscule amount of grated zucchini to the batter.

Add vegetable juice to yogurt, milkshakes, or smoothies (you can juice your own vegetables, like carrot, celery, sweet potatoes, or cucumbers).

There are now Goldfish crackers made with tomato puree and carrot puree; this is another good way to sneak in vegetables.

She notes that most picky eaters can detect the smallest amount of change, so you have to be incremental. “If you put a tiny amount in and they detect it, stop that method because they might drop that food altogether,” she adds. She recommends the book Deceptively Delicious by Jessica Seinfeld, which she says has a lot of nice tips.

Consistency in feeding

Consistency and positive experiences are key. Some tips:

Provide three meals and two snacks; don’t let kids graze all day long.

Always offer at least one preferred food per meal.

If you can, eat as a family — even if the child isn’t eating the same food you are, if they see their mom and sister eating it, this can create a positive impression.

Avoid short-order cooking. The child should get whatever the family is eating (but maybe have some yogurt or another preferred food on the table so they can see it).

Avoid stress and be patient

“I’ve seen so many families get in heated discussions, saying, ‘Well, he’s not going to starve,’ or forcing kids to eat, and it becomes very stressful for the kids. This dumps cortisol into their system, and that’s an appetite suppressant,” Hogan-Reyes explains. “Parents have to put on their acting hats and pretend like they don’t care, even though they desperately care.” She adds that if the child will take a multivitamin (with pediatrician involvement), this can give parents a level of comfort; picky eaters tend to have a higher incidence of nutritional deficiencies, so this can help.

“Another thing parents need to know up front is that this is an extremely slow process,” Hogan-Reyes says. “It’s usually effective but you have to stick with it and be consistent.”

For more expert tips, be sure to check out Undivided Conversations with Autism Dietician with Brittyn Coleman!

Picky eating vs. ARFID

We asked Coleman for information about how to help kids with ARFID. Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder is rooted in extreme food anxiety and often includes sensory avoidance of specific textures, colors, or other food characteristics. More severe than just picky eating, this avoidance can lead to nutritional deficiencies that are severe enough to interfere with daily functioning and growth.

ARFID is more commonly observed in children with developmental disabilities, particularly those with autism (up to 1 in 3 autistic kids also have ARFID). Autistic children often have heightened sensory sensitivities that make certain textures or tastes overstimulating, which can contribute to restrictive eating behaviors, low appetite, and weight loss. Kids with ARFID are also more likely to have anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), or ADHD. It’s common for ARFID to be triggered by a past traumatic experience with food, such as choking or vomiting. If your child severely restricts foods and you wonder if they have ARFID, start with a comprehensive evaluation by a healthcare professional, such as a mental health professional and/or pediatrician. Other professionals including dietitians can help rule out other medical issues and give holistic feeding support.

How is ARFID treated?

Common treatments include nutritional supplements, behavioral interventions, and therapy to address anxiety or sensory issues associated with eating. If there are concerns with choking and oral motor control, a speech-language pathologist might be brought in to address them.

If your child has an IEP or 504 plan, accommodations can include allowances for special dietary needs, structured support during meal times, and modifications to the school environment to reduce anxiety around eating.

Coleman says, “Parents can help by creating a positive and stress-free eating environment, offering a variety of nutritionally dense foods, and avoiding pressuring the child to eat. It’s important to set regular meal times and involve children in food preparation (as tolerated) to make eating a more engaging and less daunting experience.”

Coleman recommends consulting with a dietitian who specializes in pediatric eating disorders. Feeding therapy, especially the SOS Approach to Feeding, can be beneficial in helping a child expand their diet in a sensory-friendly way.

Find an occupational therapist (OT)

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor