Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) 101

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most debated and misunderstood disorders, yet more than 6 million children in the U.S. have been diagnosed with it. As a neurological disorder, ADHD commonly affects organizational skills and impulse control, regulating attention and emotions in a unique way.

To learn more about ADHD, we spoke with Dr. Hitha Amin, neurodevelopmental neurologist at Children’s Hospital Orange County, and Dr. Emily Haranin, child and adolescent psychologist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Keck School of Medicine at USC.

What is ADHD?

The first thing to know about ADHD is that the name isn’t quite accurate. There’s a myth that attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a “deficit of attention.” The truth is that individuals with ADHD have an abundance of attention; they just have a difficult time controlling it. Check out this video to hear Dr. Edward Hallowell, a leading psychiatrist working with ADHD, explain why moving from “deficit” to “abundance” language is important!

While there is so much nuance in defining and diagnosing ADHD, ADDitude Magazine states that thanks to the information we’ve acquired from neuroscience, brain imaging, and clinical research, “ADHD is not a behavior disorder. ADHD is not a mental illness. ADHD is not a specific learning disability. ADHD is, instead, a developmental impairment of the brain’s self-management system.” And while it is among the most common neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood, with 1 in 10 children between the age of 5 and 17 receiving an ADHD diagnosis, it is also not a phase or condition a child can grow out of.

Gaps in ADHD diagnosis: girls and boys

The complexity and misunderstandings when it comes to ADHD symptoms may make it difficult to distinguish between typical childhood behaviors, such as a child being seen as misbehaving or being disruptive in the classroom, versus actually presenting with hyperactive/impulsive ADHD. This might occur more frequently with boys than girls, as boys who are diagnosed with ADHD are more likely to exhibit signs of hyperactivity. They are also more than twice as likely as girls to be diagnosed with ADHD, though this may be due to clinical and research bias. It’s important to note that research has shown ADHD symptoms are less overt and show up differently in girls than in boys; because of this, they may be completely missed, resulting in lower rates of referral, diagnosis, and treatment.

Gaps in ADHD diagnosis and treatment due to race

Here’s something surprising — studies show that black and Latino kids show ADHD symptoms at about the same rate as white kids, but they’re much less likely to be diagnosed or treated. One long-term study found that by the time kids reached eighth grade, black children were 69% less likely and Latino children 50% less likely to get an ADHD diagnosis compared to white children with similar behaviors.

And even when kids of color are diagnosed, they’re not as likely to receive treatment. In one study, just 36% of black children and 30% of Latino children diagnosed with ADHD were taking medication — compared to 65% of white children.

Some people think ADHD might just be “overdiagnosed” in white children, but the research doesn’t back that up. Dr. Tumaini Coker, who led one of the studies, explained that these differences are more about underdiagnosis and undertreatment for black and Latino kids — not overdiagnosis in white kids.

So how do we fix this? Experts say closing the gap starts with a few key steps:

- Asking all parents about behavior and learning concerns at school checkups — not waiting for parents to bring them up.

- Providing care in families’ preferred languages and being mindful of cultural differences.

- Using universal behavioral screenings to catch ADHD symptoms early.

- Connecting families to support, like community programs and parent training for ADHD.

What are the primary signs and symptoms of ADHD?

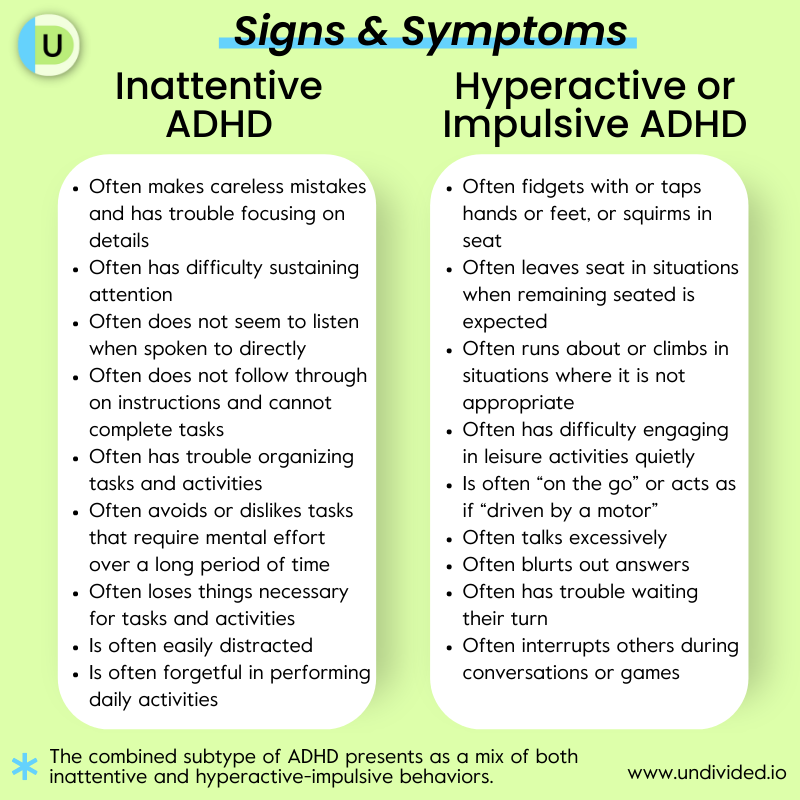

When ADHD first appeared in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-2) in 1968, it was called Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood, in response to what was then understood to be excessive motor activity. Twelve years later, with new focus on attention and impulsivity in addition to hyperactivity, the term became Attention Deficit Disorder (with and without Hyperactivity). Today, it is described in the DSM-5 simply as ADHD, with three different presentations:

- Predominantly Inattentive Presentation

- Predominantly Hyperactive/Impulsive Presentation

- Combined Presentation (showing both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms)

According to the DSM-5, the inattentive presentation of ADHD is characterized by difficulty sustaining attention or following detailed instruction, forgetfulness, poor focus, etc. Children with this type are usually more easily distracted by external stimuli. Inattentive ADHD is more commonly diagnosed in girls than in boys and can present as “spacey, apathetic behavior.”

The National Institute of Mental Health says symptoms that fall under the inattentive presentation are less likely to be recognized by parents, teachers, or medical professionals, and those with this type are less likely to receive treatment. Inattentive symptoms do not fit the hyperactive/impulsive stereotype, and this may be why ADHD in young girls is often missed (or diagnosed as a mood disorder later on).

The hyperactive/impulsive presentation of ADHD presents as a need for constant movement: fidgeting, getting out of one’s chair, being unable sit still, interrupting others, running around, etc. This type of ADHD is more commonly diagnosed in boys.

The combined presentation of ADHD presents as a mix of both hyperactive/impulsive and inattentive behaviors. For a diagnosis to be made, six or more symptoms each of inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive ADHD must be present.

How and when is ADHD diagnosed?

According to the CDC, about 75% of children with ADHD are diagnosed before age 9, and one-third of those are diagnosed by age 6. However, Dr. Haranin points out that children may also be diagnosed later in their teens or adolescence. “Part of that is because what we know about ADHD is that some children or teens don’t start to experience that impairment until the demands of the environment outweigh the strategies they’ve been using to get by,” she says. “Often we find in transitions, when children switch from elementary to middle school, we see those attentional capacities being overwhelmed.”

With diagnosis, she says, clinicians are trying to “capture the symptoms and behaviors that a child or an adult is presenting with at any given time.” However, not every child is going to fit perfectly into the specific diagnostic boxes we’ve created, so it’s important to “identify which boxes best fit and best capture what the child is presenting with. That can help us make recommendations about treatment or intervention that might be helpful.”

According to the DSM-5, in order for an ADHD diagnosis to be made, symptoms must:

- be present for at least 6 months

- be present before the age of 12 (they often begin between the ages of 3 and 6)*

- be present to a degree that is inconsistent with a child’s developmental level

- impact a child’s abilities in at least two areas of life (home, school, friendships, etc.)

- interfere with or reduce the quality of social, academic, or occupational functioning

- not be better explained by another mental or psychiatric disorder.

(Children up to the age of 16 must have 6 or more symptoms present in an area in order to meet diagnostic criteria; individuals 17 and over only need 5 symptoms to meet diagnostic criteria.)

The path to diagnosis typically begins when a parent or teacher notices some of the symptoms described earlier, such as having more trouble following directions or staying on task than is developmentally appropriate. Dr. Haranin says it’s important to show that these symptoms cause impairment, which can mean impairment in academics, in parent-child relationships, or in a child’s social relationships. She also cautions that symptoms will show up differently in different environments. “It’s not just that in school, a child is having trouble paying attention — it means that you might also see that at home, or you might also see that swimming or in baseball or in other environments.”

What does ADHD assessment look like?

An ADHD diagnosis will be based on interviews with a child’s caregivers and usually several members of their school team, and occasionally, for older children, with the child themselves. An ADHD screening evaluation that uses a standardized ADHD rating scale may also be used. This can help rule out other conditions, such as learning disorders, anxiety, autism, etc.

The interviews will focus on answering two questions: What patterns of behavior have adults in the child’s life observed, and how are those behaviors impacting the child’s life? There are many different rating scales used by healthcare providers to guide the interviews and evaluate symptoms. Depending on the age of the child, some practitioners may also use computer tests that measure attention, impulsivity, and inattention. The entire process will take time and a lot of paperwork, including a physical exam and a thorough interview about social history, family history, and symptom history.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends testing for other developmental issues when making an ADHD diagnosis, testing eyesight and hearing, and screening for [learning disabilities]/resources/specific-learning-disabilities-sld-101-1315) and mood disorders to see if other conditions are contributing to the behaviors.

After the interviews and tests, the family will have the results along with an action plan to manage symptoms, including:

- Accommodations to help the child in school, which would be added into the IEP or 504 plan

- A plan for follow-up with an ADHD expert, therapist, or psychologist

- Recommendations for ADHD medication (if considered)

- A schedule for future appointments with the health care professional to continue care and follow-up with treatment plans.

Who can diagnose ADHD?

Parents can begin by discussing their concerns with their child’s pediatrician or primary care provider, who may perform an initial evaluation and then make a referral to a qualified specialist such as a developmental pediatrician or a psychologist or psychiatrist.

Dr. Haranin says that the primary care pediatrician is one of the best (and most accessible) places to start, and it may be sufficient if a child has a more “simple” case of ADHD. (Granted, this may be hard to define.) However, she says, if a pediatrician or primary care provider “doesn’t feel comfortable making a diagnosis, or they recognize that there are some other complexities that might benefit from another professional, they can help link you to that next step.”

She recommends working with a team of professionals to get a whole-child assessment, if possible. While all professionals will use the same diagnostic criteria to make a diagnosis, different training and expertise means that each member of the team will work with the child and family to diagnose and provide treatment in different ways. “I’ve seen the best treatment plans come out of situations where a family is working with a team of professionals who can lend their unique expertise and help,” she says. “It really supports that idea of ‘humans don’t fit in boxes.’ We can all contribute different lenses, and certainly that includes the family and the child.”

Care teams may include these specialists and professionals:

- Primary care doctor or pediatrician

- Developmental pediatrician

- Child psychologist or psychiatrist

- School psychologist

- Behavior therapist

- Educational therapist

Where to start

If you want to start the evaluation process, you can find a specialist through your child’s pediatrician, a school psychologist, your insurance plan, or your local chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness or CHADD. An ADHD support group can also be a great source for local referrals.

Getting in to see a specialist for a psychological assessment can be challenging due to long wait lists and a shortage of child psychologists and psychiatrists, however. If you suspect that your child has ADHD and they do not already have an IEP or 504 plan, Dr. Haranin recommends requesting a special education evaluation.

You can learn more about special education evaluations in our article IEP Assessments 101.

Note: Make copies of documents showing that your child is diagnosed with ADHD so that this documentation is available when your child is an adult. Having proof of this diagnosis from childhood should make it much easier to access treatment as an adult.

How do co-occurring diagnoses affect ADHD interventions?

A co-occurring condition is a separate diagnosis that exists simultaneously with ADHD and doesn’t go away with the treatment of ADHD. According to psychologist Dr. Thomas Brown, about 67% of children diagnosed with ADHD have at least one co-occurring learning disability or mental health issue. For example, 45% of all children diagnosed with ADHD have a related learning disability, compared to just 5% of typically developing kids. Children with ADHD are also up to three times more likely to have an anxiety disorder and five times more likely to have depression than kids who don’t have ADHD. Tic disorders are another common co-occurrence with ADHD. There is also evidence that ADHD and autism are commonly co-occurring conditions—40–70% of people with autism have significant ADHD symptoms.

ADHD symptoms can mirror other medical conditions and mental health concerns, such as anxiety or difficulties with executive functioning, so it’s important for a healthcare professional to figure out whether a symptom can be attributed to ADHD, a different disorder, or both. For example, Dr. Haranin says that sleep disorders can impact attention while constipation can impact children's behavior, resembling ADHD or other behavioral challenges. Secondary problems may also be present, such as behaviors that arise as a way to cope with ADHD symptoms. A recent study also found that behaviors resulting from trauma (poverty, divorce, violence, family substance abuse, etc.) can overlap with ADHD symptoms, complicating diagnosis and treatment.

It can be tricky to differentiate between an ADHD symptom, a symptom of a co-occurring condition, and a secondary problem. For example, Dr. Haranin says, “at school, if it’s a math lesson, the expectation is the child is focusing and attending to the math lesson.”

How do we make sure our children aren’t being misdiagnosed?

Dr. Amin tells us that multidisciplinary assessments are the most appropriate if co-occurring conditions are present, but it’s sometimes not possible to tease out the root of each individual issue during assessment. In that case, a child can be seen and evaluated, but a diagnosis may be deferred until there is a clearer picture.

In treatment planning, most healthcare professionals will decide which disorder to treat first based on the impairment that those symptoms are producing in the individual’s life. Dr. Haranin says a child’s caregivers, teachers, coaches, and others involved in their daily life are essential reporters when it comes to determining which symptoms are causing a child the most impairment. Clinicians should also include children as much as possible, she says. While asking them about their experience is not always effective, “we try to figure out what symptoms or what specific things are really causing them the most stress. What is the most ‘impairing symptom’ that they’re experiencing? Some of these things can happen at the same time. So we try to figure out what's causing the biggest problem and how we can address that first, then see if those other concerns are still present.”

Having a thorough medical history is key to differentiating between ADHD and co-occurring conditions. For example, symptoms and/or behaviors due to anxiety, a mood disorder, or secondary problems will usually start at a specific time or occur only in certain circumstances (only when taking a test or only upon starting high school), while ADHD symptoms are chronic and pervasive (apparent from childhood and persist in almost every life situation).

For more information about autism and ADHD, read our article Autism and Co-Occurring Diagnoses.

The link between executive functioning and ADHD

Difficulties with executive function result in issues with organization and memory. A child who struggles with executive function may have trouble organizing their school materials, retaining information while reading a book, or writing a school paper because they can’t organize their thoughts — no matter how hard they try. While there is no diagnosis in the DSM for “executive function disorder,” up to 90% of children with ADHD experience executive dysfunction. Some experts even define ADHD as “a developmental impairment of executive functions — the self-management system of the brain.”

Because ADHD and executive functioning issues often occur together, by addressing the executive functioning weaknesses through environmental modifications and other accommodations, we can help individuals use their executive functions to self-regulate, stay on task, and attain their goals.

Emotional dysregulation: What is “rejection sensitive dysphoria”?

While the diagnostic criteria for ADHD doesn’t mention problems with emotions and mood regulation, studies show that as many as 45% of children with ADHD also have difficulty with emotional dysregulation. One aspect of emotional dysregulation is called rejection sensitive dysphoria (RSD), something psychiatrist Dr. William Dodson describes as “a triggered, wordless emotional pain that occurs after a real or perceived loss of approval, love, or respect.”

First, it’s important to understand that rejection sensitive dysphoria is not a diagnosis. The term describes an extreme emotional sensitivity and pain that’s triggered by a sense of rejection or criticism by important people, such as parents/siblings, teachers, or peers. Dr. Dodson writes that approximately one-third of adolescents and adults list RSD as the most impairing aspect of their ADHD.

Impact of RSD

There is very little research or data on RSD and no official symptoms. However, that doesn’t mean that children with ADHD can’t also struggle with negative messaging and rejection.

“A lot of children with ADHD have had far more negative terms being used,” Dr. Amin says. “So if you’re constantly in an environment where you grow up hearing those messages, it is easier to get upset when someone gives negative feedback.” And then there’s the neurological factor: Dr. Amin explains that the ADHD brain is “unable to tone down the signals from the amygdala,” a part of the brain that is associated with regulating emotion. She also mentions that co-occurring conditions, such as a sleep disorder, may impact emotional regulation. If you’re constantly sleep-deprived, it’s much harder to regulate emotions.

Addressing emotional dysregulation is similar to addressing symptoms of ADHD. Therapy can help a child learn to develop coping skills related to how to process, manage, and contain feelings so that they’re less overwhelming. Children with ADHD may have a tendency to latch onto negative messages, Dr. Haranin says, so using praise and reinforcement rewards to motivate positive behavior is key:

Treatment for ADHD in children

Treatment of ADHD is often multimodal, meaning a combination of different complementary approaches, and it can include behavioral, educational, psychological, and medical interventions. It should be tailored to the unique symptoms and needs of the child, meaning it will look different for everyone. One child might need ADHD medication coupled with behavioral therapy while another needs behavior skills therapy or training coupled with other lifestyle changes. When it comes to school, a child’s team should consider educational program modifications and supports, including accommodations in IEP and 504 Plans, tutoring, and/or other special education services.

Medication

Medication is not recommended for children under six years old since it is known to cause more side effects in younger kids; research is still being conducted on potential long-term effects of starting ADHD medications at this age. Children with certain co-occurring diagnoses such as Down syndrome may not be good candidates for medication.

Dr. Amin adds that this choice will depend on the age of the child, other co-occurring conditions and factors, and parental preference. Non-stimulant medication is typically prescribed to younger children or children who may have a sleep disorder or autism, while stimulant medications are typically prescribed to older school-aged children, usually when ADHD is diagnosed. She highlights lifestyle as a factor as well — for example, if medication is only needed on certain days, times, or during certain activities, a stimulant medication may be easier to start or stop as they are fast-acting (within two hours) and short acting (effectiveness stops working once an individual stops taking them).

“All of these decisions around treatment for a child who is diagnosed with ADHD are very individual, and families have to really think about what approach they’d like to use,” Dr. Haranin says. “Medication is not always warranted [but] it can be a really helpful and important part of a treatment plan for many children with ADHD.”

Behavior therapy

Behavior therapy is a foundational approach to ADHD, and can be equally important, Dr. Amin says — whether it’s with a psychologist, licensed therapist, or licensed social worker to work on reducing disruptive behaviors, work on organizational skills, and improve a child’s relationship with peers. “There was a landmark multimodal treatment association study, and they looked at outcomes with medications alone, medication plus behavioral approach, and the behavioral therapy alone. The best outcomes were with medication and behavioral approach together.”

She adds that effective treatment, whether medication or behavioral techniques, can change the quality of life for the child and for the parent as well as prevent long-term damage to self-esteem. “If the child keeps hearing negative feedback or criticism from school or at home, that can significantly hamper their learning,” she says.

Dr. Haranin explains why behavioral parent training can be important for younger children, and why teaching organizational skills through behavior therapy is paramount for older children and teens:

IEP and 504 accommodations for ADHD

Of the 13 eligibility categories that qualify a child for an IEP, ADHD falls into the classification of “Other Health Impairment (OHI).” But because IDEA is very specific with what qualifies as a disability, sometimes children are denied services unless the ADHD is shown to be severe enough to cause major impairment and adversely impact educational performance. However, children who are unable to qualify for an IEP may still be able to receive services and supports under a 504 plan.

The following are some common accommodations that may be included in a child’s IEP or 504 Plan to help them succeed in school:

- Adjust formats for reading and writing assignments to help with visual scanning and/or remaining seated. (This includes using technology such as audiobooks to help a child complete tasks.)

- Combine tasks with a physical action, such as using manipulatives.

- Provide a visual schedule.

- Provide prompts to help a child stay on task.

- Allow more time to complete tests and homework (usually specified time and a half).

- Provide more breaks and opportunities to move around throughout the school day.

- Allow flexible seating options (standing, wobble chair/stool, rocker, etc).

- Address any learning gaps in math, reading, and writing that may have resulted from previously undiagnosed ADHD.

- Create goals to improve how they socialize with their peers, since kids with ADHD are more likely to be bullied.

- Provide positive reinforcement and feedback.

- Allow use of fidget.

- Provide preferential seating in front of class

- Provide support for executive functioning needs such as organization systems and limiting distractors in the classroom (e.g., posters on the walls)

You can find additional suggestions in our article List of Accommodations for IEPs and 504s.

ADHD and a strengths-based approach

There’s a lot of stigma around ADHD, which may make it hard for a child with ADHD to feel understood. A strengths-based approach allows children with ADHD to redefine themselves and form positive-focused concepts of self. It also allows them to explore what makes them unique and gain confidence to do all the things they’re great at. (For more, check out Emma A. Climie and Tasmia Hai’s article “Positive Child Personality Factors in Children with ADHD.”)

To learn how to take a strengths-based approach in special education, including creating strengths-based IEP goals and accommodations, check out our article on the topic!

Supporting your child with ADHD at home

At home, you can help your child build on the skills they are learning at school. Some educational therapists offer executive functioning support, and you can get more ideas from our conversation with educational therapist Marcy Dann about building executive functioning skills.

In addition, be sure to talk to your child about their disability. Understanding how their brain works and the potential benefits that come with having ADHD can help empower them and develop their advocacy skills.

Support my child with ADHD

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor