Bullying and Kids with Disabilities

What is bullying?

People often think of bullying simply as people being mean, but there is more to it than that. The American Psychological Association defines bullying as “a form of aggressive behavior in which someone intentionally and repeatedly causes another person injury or discomfort. Bullying can take the form of physical contact, words, or more subtle actions.”

Arroyo explains that while bullying can look different (physical, psychological, social, online/cyber, etc.), it usually contains some common elements: it’s repeated, unwanted, and involves an imbalance of power. He explains:

- Repeated: “It is some kind of unwanted, aggressive behavior, that's intentional and gets repeated over and over again,” Arroyo says.

- Unwanted and aggressive: “Bullying is ultimately that idea of someone's getting picked on, something bad is happening—whether it's isolation or being made fun of,” Arroyo says.

- Imbalance of power: “It usually includes an element of an imbalance of power,” Arroyo says. “And that power can be anything—it can be power of strength/physical size, power of, ‘You're different and I've got other people like me and we're all going to make fun of you because you're different,’ or that they've got embarrassing information about the person.”

And don’t forget: bullying isn’t limited to children. Adults can be bullied too.

Typically, the bullied individual does nothing to “cause” the bullying. A power imbalance can simply be a result of a student’s reluctance to defend themselves, or an inability to do so, especially “when you're talking about students with significant disabilities and a student who does not have that [ability to defend themselves],” Flier says.

Flier also adds that there needs to be an element of intention, that the bully intends to cause mental harm to the victim, rather than the unintentional harm that may come from regular interactions with kids with great differences. She explains how to talk with your child to try and assess whether a painful interaction with a peer was intentional:

Is it bullying to exclude another kid?

Social exclusion, while not always intended to hurt, can also be experienced as bullying and have similar effects. When a child doesn’t have friends, sits by themselves at lunch, and/or isn’t included in other kids’ social activities or conversations, the effect on that child’s mental health can be long lasting.

Dr. Chad Rose explains that the research shows that the impact of social exclusion is just as bad for short- and long-term outcomes as physical or verbal bullying. “I think everybody can imagine what it would be like if every day you go to school and you feel like you're alone among your peers. That's not good for your mental health at all,” he says. Dr. Rose explains that often, adults want kids to navigate or solve problems independently, using their problem-solving skills, but there are some contexts, like being socially excluded daily, that require some extra help. That’s the one area of bullying prevention that we can do a better job with within schools and even as parents, he explains.

What is cyberbullying?

Bullying also increasingly takes place within cyberspace, especially in social media channels. Sarah Flier says that cyberbullying is often related to people feeling excluded. However, the same rules apply — to be considered as cyberbullying, the exchange must be repeated, be intentional, and feature an imbalance of power.

“Cyberbullying is real,” Dr. Pelangka says. “Students, parents, and administrators need to be aware that nowadays, with students having access to their phones on campus, they can purposely film other students and share the videos in social media platforms with the intent to make fun and harm. It is virtually impossible to monitor this on all fronts. However, parents should communicate with their districts and site administration about their child’s privacy to ensure their children are not being discriminated against.”

Remember that cyberbullying between school children can occur outside of school but should still be addressed by the school since it can still get in the way of learning and affect a child’s health and safety within school.

PTA Smart Talk is a tool that helps families have a discussion about digital safety. Safekids.com has an example online safety contract that helps families discuss do’s and don’ts.

How can and should schools address bullying?

Once upon a time, schools might have considered bullying to be an inescapable feature of childhood. Today, however, schools can and should have a proactive policy to address it.

On a national level, policies to protect children with disabilities from bullying are overseen by the U.S. Department of Education. For children with disabilities, the Department advises that under Section 504 (the Rehabilitation Act) and Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act, “Schools must address bullying and harassment that are based on a student’s disability and that interfere with or limit a student’s ability to participate in or benefit from the services, activities, or opportunities offered by a school.”

States may have additional legislation to protect students from bullying and hold schools accountable. For example, in California, every school is required by the California Education Code to have an anti-bullying policy, which should be provided to parents and posted on the school website. For example, LAUSD’s webpage on bullying and hazing provides information about the district’s anti-bullying policy, anti-bullying lesson plans, and more. The principal of each school in the district is responsible for implementing the anti-bullying policy.

Dr. Rose says, "I believe that all schools should have a Bullying Prevention Task Force—a task force that examines bullying reports, that examines the interventions that are implemented, and is also in charge of doing school climate assessments. All schools should be doing a school climate assessment to get the pulse of the school—giving students voice to what bullying is and asking students how often it's happening, where it's happening, and under what circumstances. The other thing that I would recommend all schools do is a behavior or risk screener to identify youth who may be at risk of being involved in bullying. Maybe they're not heavily entrenched, but they're at risk. That way, we can offer services before it becomes a problem."

Anti-Bullying Programs

Schools can address bullying at a whole-school level by creating an anti-bullying culture at school and teaching kids to be upstanders. Some evidence-based programs include the following:

- Bullying Prevention from PBIS is a free, whole-school bullying prevention program that is designed to be incorporated as part of a school’s comprehensive PBIS plan. It includes a program called Stop, Walk, & Talk that teaches elementary students how to react to bullying behavior either addressed to themselves or to others around them, and Expect Respect is for middle and high school students.

- Second Step Bullying Prevention Unit is a whole-school bullying prevention program designed for grades K–5 used in many schools.

- The Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP) is designed for K–12 at four levels: individual, classroom, school, and community.

- StopBullying.gov offers a list of strategies that are not advisable. For example, enacting “zero tolerance” policies that lead to instant suspension can deter kids and adults from reporting bullying.

Other Bullying Prevention Resources

There are many other evidence-based resources that schools can use for bullying prevention, including those that can be integrated into other activities. You may want to:

- Show the NED Show’s “Preventing Bullying” video short to kids to start a conversation about how to be an upstander.

- Use internet research to have kids look up types of bullying, how to prevent it, and how to respond. The Pacer Center has some great resources for kids about bullying.

- Role-play how to stop bullying.

- Hold discussions or classroom meetings on reporting bullying or peer relations.

- Use creative writing or making art such as a collage about respect or the effects of bullying.

For more information about why these programs are so important when it comes to empowering kids, and how they can be implemented, listen to Flier’s explanation here!

Bullying prevention can also be incorporated into the classroom. Dr. Rose says that teachers can help prevent bullying by embedding social communication skills into their daily curriculum. "If I'm teaching a math lesson and I have three objectives, I can add a fourth objective that is related to social or communication skills. For example, if I have students engaging in activities in a group, we can add the objective, ‘I'm going to be looking at how well you're collaborating with one another,’ or, ‘I'm going to be looking at how well you're asking help from one another.’ Having that as an objective and doing that for all of our daily lessons will teach kids that social interaction with one another is just as important as the academic content. When we prioritize these social and functional skills, then we have less bullying in our schools because kids are learning how to interact under the supervision of their teacher."

What can parents do about bullying?

Dr. Rose points out that the first hurdle is knowing when your child is being bullied. He says that parents should watch for any behavioral change, which is a direct indication that something is wrong: “If you see a shift in behavior, that's time to have a conversation. The other thing that I strongly recommend to parents is having conversations with your kids. We get in this routine as parents: we’ll pick up our kid from school, or they'll come home, and we'll say, ‘How was your day?’ and they’ll say, ‘Fine,’ and we go about our way. I would encourage all parents to start asking direct questions.” Some examples he gives: What made you laugh today? What did you learn? What did you play during recess today? Who decided what you played at recess?

He explains that the main reason is to open up the line of communication so that if there is a problem, your child will come to you for help. The other piece is to learn who your child is interacting with: who is their friend group, and is it consistent every day? For example, if you ask them, “Who did you play with today?” and their answer changes from one day to another, that should prompt more questions from you.

1. Talk to your child if you suspect bullying.

If bullying is happening, the first step is to talk to your child about it, then talk to the school. "If we can really teach kids how to view social situations through a socially appropriate lens, then we’re better off. But most importantly, having conversations with kids and not having them figure it out on their own. Because there’s this hidden curriculum—social rules and norms that everybody seems to know but aren't directly taught. For our kids with disabilities, sometimes they don't catch onto those social rules and norms, and we have to teach them. But teaching every kid these things is just as important," he tells us.

2. Talk to the school.

It’s extremely important to talk to the principal, your child’s teacher, and/or a school counselor as soon as you have discussed the issue with your child. School staff may be unaware that it is happening and will want you to report it. It’s also important to act on the information as soon as you hear about it because this is the time to use preventative measures, so it doesn’t continue to occur or grow worse. Flier explains:

3. Work with the school to keep your child safe.

Both Arroyo and Flier agree that it can be difficult for children with disabilities to understand bullying. Arroyo advises against any kind of forced make-up interaction between the children involved. Bullying is not resolved using mediation or conflict resolution strategies since the conflict was unfairly created by the bully in the first place. Expecting children to interact with their bully can also be difficult for children with disabilities to understand, and it sometimes extends the feeling of disempowerment.

Dr. Rose says, "A lot of times, adults want kids to navigate things independently or use their problem-solving skills. But there are some contexts like being socially excluded daily that need some assistance or need some help. To me, that is the one area of bullying prevention that we can certainly do a better job with."

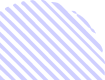

Arroyo and Flier recommend taking the following steps:

- Support your child and believe what they're telling you. Take it seriously.

- Take as much information from your child as you can. Try to establish a timeline of what has happened and how often.

- Become familiar with your school or district's anti-bullying policy posted on their website and your state's bullying prevention laws.

- Reach out to your child’s teacher, including the school counselor and the principal on the same email. You can also ask for a meeting. Document everything — create a paper trail so that it’s not your word against someone else’s.

- Give the school time to interview all the kids and adults involved, and review any video footage to establish what happened. The adults at school need to talk to the bully.

- If a weapon is involved, call the police.

- Work with your school team to develop a safety plan that will protect your child against future bullying. This may involve adding accommodations to their IEP or 504 plan. Your school or district may have a bullying safety plan template they use for this purpose. Here is a bullying safety plan checklist of questions you can review with your team.

Climb the chain of command until you can reach the principal, the director of special education for your district, the superintendent, and the Board of Education as necessary. If the school’s response is not adequate, write a Gebser letter. (More details on this below.)

Here are some more tips and strategies from Arroyo on the various approaches to preventing bullying among children, such as establishing connections with schools and leveraging the available legal protections:

How to talk to your child about bullying

The State Council on Developmental Disabilities recommends teaching your child some strategies to deal with bullying, including practicing possible responses to bullying ahead of time. Arroyo says that while people tend to advise that a child “just ignore it and they'll go away,” the truth is that when a child ignores their bully, the interactions are likely to continue — in part because kids tend to look down or away when they pretend to ignore abuse, and that’s all the bully needs to know they’ve been successful at getting to them.

Here are a few examples of some lines to rehearse:

- Strong messages such as “Stop it,” “Leave me alone,” or “I don’t like to be treated this way.”

- Humor: For example, if the bully says, “You sure do have a big nose,” you could say, “I know, just like Rudolph, the red-nosed reindeer.” Or if you wear glasses and kids call you “four eyes,” you could say, “The better to see you with,” like the wolf in Little Red Riding Hood. Sometimes by gently making fun of yourself, you take away the bully’s chance to do it.

- Not caring: “Whatever” is a good neutral comment that gives the bully little satisfaction and shows that the student was not bothered or upset. Other ideas could be “Big deal” or “Who cares?” or “Is that supposed to be funny?” or “So?”

- Slightly sarcastic: In response to “Stupid outfit,” you might say “Thanks, I’m glad you noticed.” Or if someone says, “You smell,” you could answer, “Wow, you could tell I showered!”

- Easy to remember: “I don’t like that” gets attention, and if you can, say what you didn’t like, such as a rude name or bad words.

Make sure to tell your child that the bullying is not their fault. It’s also important to give your child the space to feel what they need to feel. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network is a good resource.

What can you do if the school doesn’t respond appropriately to bullying?

According to the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) and the Department of Ed, when bullying interferes with a disabled student’s ability to access their education and related services, it could be a violation of their right to a free and appropriate public education (FAPE).

If bullying is serious enough, it creates “a hostile environment” — in other words, it is repeated, intentional, and impedes the child’s ability to access their education or affects their health (for example, by making them want to skip school or preventing them from using the bathroom). If the school is aware of the bullying and doesn’t respond appropriately to stop it, a parent may need to write a Gebser letter. Named after a 1998 Supreme Court ruling, a Gebser letter is a signal to the school that the child is being discriminated against by the school’s inattention to the issue.

It is also the first step toward making a formal disability discrimination complaint with the OCR. Learn more about Gebser letters here and find a sample letter for Undivided members here.

What if your child with a disability is accused of bullying?

Children bully for many reasons. They may feel socially insecure or be copying adults who use inappropriate behavior management strategies. Moreover, when children with disabilities lack social skills, their actions or words may be misconstrued by other children and adults.

Dr. Rose says, "If we think about kids that have behavior disorders, for example, they tend to engage in aberrant behavior under normal circumstances more than other youth. Some of those behaviors may look like bullying to others, but these kids are using some aggressive behaviors often as a form of communication. They don't know how to communicate their thoughts, wants, needs, and desires, so they engage in behavior that can be interpreted as bullying. The reason why I want to make that distinction is because that tells me that services need to be provided in schools to help these kids communicate in a socially appropriate way."

As Arroyo explains, parents should first consider any accusation in the light of their child’s overall behavior. It’s important to ask for more information to work out whether the bullying behavior is related to their disability. A child whose behaviors affect the learning of their classmates needs a functional behavior assessment. If a behavior intervention plan or behavior support plan (BIP/BSP) is already in place, check that it was followed. Remember that bullying is a behavior that can be changed.

What should be done to address bullying in the IEP?

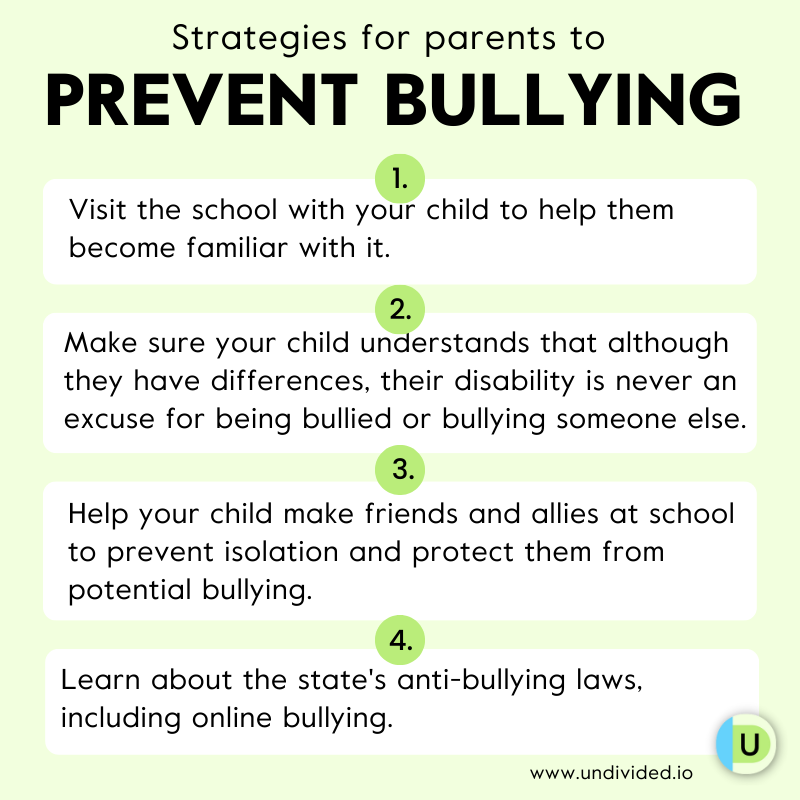

While there is plenty of information out there about how to help your student self-advocate and how to protect them from being bullied, some of it may sound better in theory than it is in practice. Dr. Pelangka recommends the following practical ways in which a student can be supported through their IEP to help them better recognize and respond to bullying behavior:

Address the need through social pragmatic language intervention with a speech and language pathologist. If your child struggles with identifying social cues and differentiating between bullying and light humor, this may be an area of need, and working on their social pragmatic deficits can support them in the first step: identifying that they are in fact being bullied (verbally).

If a student is struggling with self-advocacy and/or self-concept as a result of bullying, this can be supported by adding in self-advocacy goals, and possibly adding in counseling services, to support that area of need.

- Many students — particularly those with autism — may fall victim to peer pressure and poor social influences, which can be used by bullies; their peers may intentionally tell them to do things that are unsafe or embarrassing. This can be addressed by adding safety awareness and/or social pragmatic goals to the IEP, service minutes to support that, and accommodations such as but not limited to:

- Adult supervision during unstructured times/passing periods (however, make sure you consider your child's need for autonomy and independence)

- Adult supervision in PE locker room and having a PE locker near the PE teacher area

- Access to safe space on campus such as a teacher or counselor they can always go to

- Parents also need to be mindful of bullying behavior taking place on the bus. The student can sit directly behind the driver as an accommodation.

“Personally,” Dr. Pelangka says, “I believe the best defense against bullying is psychoeducation: informing the larger student population about differences and encouraging an inclusive mindset. Parents can have on-site ability awareness trainings — where professionals go in and educate students (and staff) on the various differences and abilities that students at their schools may have — written into their child’s IEP to help promote this practice.”

Bullying is not just a problem in schools. As Dr. Rose points out, we have to teach our children that bullying is not acceptable, as well as how to cope with it.

Address school bullying

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor