Socialization and Inclusion: Nurturing Authentic Peer Relationships

For any parent, watching our children struggle to find friends can be painful. For parents of children with developmental disabilities, such struggles are common, and often persist throughout the school years and beyond.

In fact, many parents report that the biggest challenge their children face, especially as they age, is the absence of authentic friendships. The social world of a child with disabilities is often limited to an inner circle of immediate family members and an outer circle of paid adult helpers, such as aides, teachers, and therapists. Expanding these circles requires that parents take an active role in facilitating meaningful peer relationships, both within and outside of school — but how? And what resources are available to support parents and children?

To address some common questions about fostering peer relationships, we spoke to Dr. Mary Falvey, Emerita Professor from the Division of Special Education and Counseling at California State University Los Angeles and a national authority on inclusive education, and Dr. Sarah Pelangka, BCBA-D, special education advocate and owner of KnowIEPs. We also spoke to staff at the Friendship Foundation, a nonprofit group that connects neurodivergent and neurotypical peers through online and in-person programs and activities.

Does my child need typically developing friends?

We all benefit from having diverse friends. Our children are no different. Having friends with different abilities, interests, and backgrounds can enrich us and open us to new possibilities.

There are practical reasons, too: children with disabilities live in a world of predominantly non-disabled people. They need to know how to interact socially. This is important not only for their social-emotional well-being and their success in school now, but also for their future.

Creating opportunities for your child to socialize with peers when they are young is important, and often easier than when they are older. Young children — even children who are very different from each other — often play together naturally. Dr. Falvey says that what we know from research is that children are most likely to form friendships where there’s close proximity and frequent opportunity:

What if no one asks my child for a playdate?

Remember that scheduling playdates takes work, whether our child has disabilities or not! In the beginning, you may have to be the one facilitating opportunities to connect your child with non-disabled peers. Our experts agree that getting involved in the school’s PTA, though time-consuming, can help. “A lot goes on in those meetings,” says Dr. Falvey. “Getting involved as a parent in those PTA meetings can actually help to elevate not only you but also your family in that community, and people begin to see you as a member of that community.”

Cull agrees. “You need to work as a group with other parents in your school. You need to try and involve parents who don’t have children with disabilities,” she says. “And I know most parents with a child with a disability are like, ‘I can’t do PTA, I’m way too busy.’” But finding even a small role in the PTA can pay off. Cull suggests raising questions that will affect not just your child but other parents’ children, such as dietary inclusivity at a school event. Inclusion applies to all children and is a concept many parents of students from different cultural, economic, religious, and other backgrounds can identify with.

When you do initiate a playdate, Cull’s advice is to choose an activity that is fun and structured, invite more than one child to avoid awkward one-on-one scenarios, and provide lots of support. You may or may not want siblings present: they’re good at modeling how to communicate with your child with disabilities, but they may also detract attention away from them. Dr. Eileen Kennedy-Moore says that you can support your child for a successful one-on-one playdate by setting up limited choices beforehand with your child to offer their friend.

How do I help my child make friends in middle and high school?

When they’re young, pairing children up by interest isn’t as essential because they’re more likely to play together with whatever is at hand.

In middle and high school, look for clubs that overlap with your child’s interest areas, such as choir, band, or drama. Aside from formal clubs, many middle schools offer a lunchtime activity, such as a weekly board game day, to help facilitate socialization not only for kids with disabilities but for any kids who have trouble making friends — which in middle school may be true of a lot of kids! If the school doesn’t offer anything, consider starting a lunchtime club (more on this below).

Check out this clip for Dr. Falvey’s advice for socializing with peers and what to write into an IEP:

What if my child has very different interests from other kids their age?

When a child has interests that aren’t considered age-appropriate — for example, a fourteen-year-old who loves Frozen — parents may feel anxious or pressured to mute these interests in order for their child to fit in. But our goal isn’t to change our children. While helping them develop social skills and find common interests is important, so too is honoring who they are. Dr. Pelangka suggests looking for compromises. For example, if your Elsa-loving teenager is playing Uno with peers, use a Frozen-themed set of Uno cards. Your child will feel more engaged, and the game will be no different.

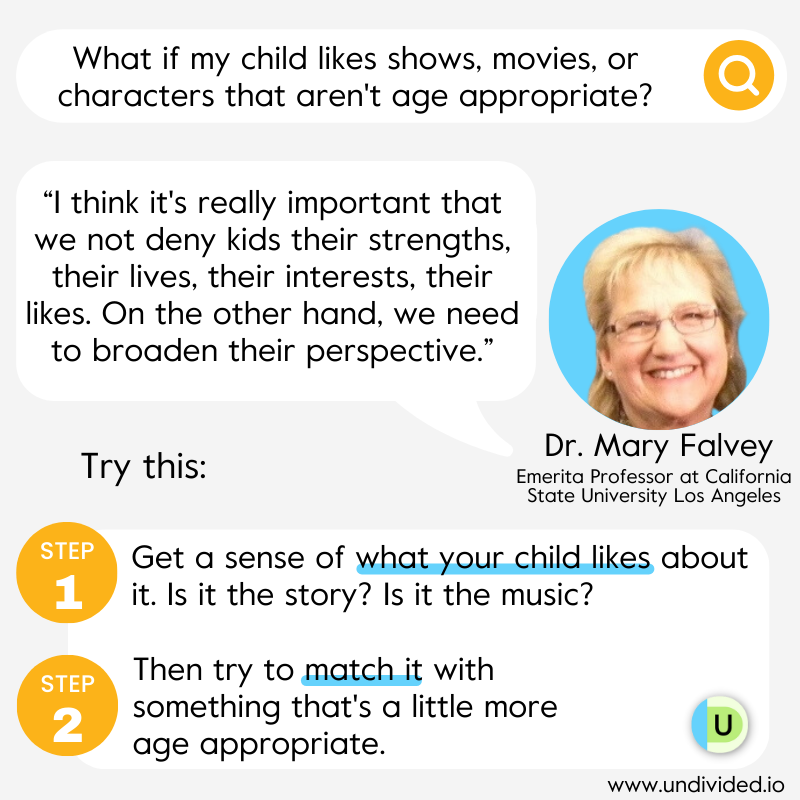

Identifying why our kids like the things they do can help us introduce similar interests that help them relate with their peers. Dr. Falvey gives great examples in this clip:

Other children don’t know how to communicate with my child. How can I teach them?

Modeling, modeling, modeling.

Modeling is an evidence-based practice that parents can organically incorporate into playdates. Dr. Falvey says that through modeling (and without a lot of fanfare), we can demonstrate techniques that we use for communicating with our child, such as allowing a period of silence to pass without expecting an immediate response, or using yes and no cards to facilitate choices. Siblings can also be good models for similar-age peers.

It may be important to explain to the other children what’s going on. For example, if your child is flapping their hands, explain that this is one way they calm themselves. Or if your child is quiet, explain that this doesn’t mean they’re not interested; it’s just that speech is challenging. “I think a lot of people assume that not talking means not thinking, or not talking means not having an opinion,” says Falvey. “I often say that children are not too delayed to have opinions about things. It just might not look the same or sound the same as somebody else.”

If your child does something unexpected, like knocking over a tower of blocks as it’s being built, Falvey reminds us to let the other kids know that it’s okay to express their feelings (such as hurt or disappointment) in response. “Helping the kids be able to say honestly what they’re feeling, yet not doing it in a way that’s hurtful or bullying to the other children, is so important.”

If your child uses AAC, Dr. Pelangka recommends that same-age peers in school get some level of training, and that this be written into the IEP:

Research strongly supports the social benefits of inclusion. Effective inclusion gives children a sense of belonging and ensures that they will have access to the same extracurricular opportunities as their peers. A 2020 study found that students in a fully inclusive environment not only performed better academically and made more progress on IEP goals, but they also had more social interactions throughout the school day. Whether your child is in an inclusive or a special education classroom, facilitating social opportunities largely comes down to practical advice and dogged effort. Build inclusion into every IEP; seek out or create lunchtime social clubs with support from organizations like the Friendship Foundation; and make sure your child has equal opportunities to participate in activities that interest them, like choir or drama, with appropriate support (more on all of this below). And don’t forget about the social benefits of joining the PTA!

There are several ways to write socialization into a student’s IEP. Undivided’s Education Advocate, Lisa Carey, recommends the following:

- Write speech goals that facilitate peer interaction. Speech goals around pragmatics (which means social communication) are a great place for this. For example, if your child has a speech goal that focuses on turn-taking, you could write a goal that begins with this language: “In a small group that includes peers with and without disabilities, [the student] will . . . ” By specifying that the student will work alongside both typically developing and disabled peers, you can make inclusion happen. (Lisa adds that this can be particularly useful for push-in services.)

- Use classroom peers as models to encourage inclusion. Goals for learning class routines — such as lining up for recess or participating in class discussion by raising their hand — can specify that a student use peer models to work on classroom tasks. “As kids get older, learning to use peer models becomes a self-accommodation,” Lisa says. A student can look at a peer’s book if they don’t hear the page number the teacher says, for example. “This is something we do all the time as adults,” Lisa says, “and it’s one of the reasons we like inclusion: we teach our kids to use those peer models.”

- Request recreation therapy, which is specifically intended to help students learn the skills necessary to participate in the social aspects of education. It’s also one of the related services that not enough parents know about. The IDEA describes recreation services as including the “assessment of leisure function, therapeutic recreation services, recreation programs in schools and community agencies, and leisure education.” Recreation therapy services can be provided both at school and through after-school programs (such as those offered by the local parks and recreation department or youth development programs).

- Find a social club! “I encourage lunch clubs,” Lisa says. “I bring those up in almost every IEP meeting, but it’s really hard to write as a goal. In a gen ed classroom, a teacher can facilitate the child participating in a group discussion, but you can’t make other kids go to a LEGO club, for example.” Most clubs are sponsored by a teacher, so you can talk with the school about ways to facilitate inclusion.

And as Dr. Falvey says, IEP goals are centered around what a child will be able to accomplish or achieve by the end of the school year. That can include making friends. Hear her explain how to write socialization into IEP goals in the clip below:

First, check what your school already offers. Many elementary and middle schools and some high schools have lunch club activities. They are usually held once a week, and are topic-specific and voluntary.

If you decide to start a club, you’ll need to find an adult to supervise (usually a teacher), and a space (often, the supervising teacher can host the club in their classroom). Friendship Foundation, which hosts inclusive lunchtime “Friendship Clubs” in thirty-five schools across ten districts, can offer support and guidance for parents interested in starting a lunchtime club. Michelle Manzano, School Programs Director, says that navigating lunch schedules and finding a teacher liaison can be daunting at first, but once the club is going, it’s pretty easy. To learn more about the Friendship Foundation’s programs, watch this clip with Michelle and the foundation’s Program Development Director, Daniel Stump:

Our experts note that many family-centered community activities can be an opportunity to network with other parents and connect children to peers, too. Remember that some aspects of raising children are the same whether they have disabilities or not. Some opportunities and resources in your community may include the following:

- Scouts can be a great source for structured social activities outside of school. If a club isn’t as welcoming as you’d like, reach out to the Scouts’ Special Needs Chair for support, or consider becoming a pack leader yourself.

- Organizations such as Friendship Foundation create myriad fun opportunities for neurotypical and neurodivergent kids to become friends, from summer camps to “Zoom Pals.”

- Activity-based groups such as Anchorless Productions unite children with disabilities and typically developing peers around activities such as producing plays.

- Your local parks and recreation department likely has offerings such as dance, arts and crafts, or Zumba classes as well as summer camps and sports leagues.

- Local chapters of Autism Society, Down syndrome organizations like Club 21, and similar organizations offer parent support, recreational activities, and other resources.

- Sports leagues — and not just leagues for kids with disabilities — provide great opportunities for fun, meaningful peer interaction. Your child has the right to access the same opportunities as other children. Leagues and camps on public grounds are required to accommodate children with disabilities.

- Martial arts clubs provide a consistent social outlet, and some research has shown it to have social benefits, particularly for children with autism.

Other state-supported programs may be available. For example, California Regional Centers offer social-recreational funding so that families can access opportunities for their children to participate in recreational activities such as theater and sport programs, swimming lessons, and summer camps with peers.

What opportunities have you found for socialization and inclusion to help your child build meaningful relationships? We’d love to hear your ideas!

Set up community supports

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor