Who Pays for Medi-Cal and Other Disability Benefits for Kids in California?

At Undivided, we spend a lot of time talking about how families can access funding for all the services our children need. We often point families to private health insurance or to free or low-cost resources — but a good chunk of the funding sources we look to are public funds. With potential federal cuts on public programs being proposed, we thought it would be helpful to review where the money comes from to understand how these cuts could affect Californians.

Sources:

- KFF analysis of Urban Institute estimates based on FY 2022 data from the CMS-64

- California Health Care Foundation, Medi-Cal Explained: Medi-Cal Financing and Spending

- Department of Developmental Services 2025-26 Governor's Budget

- CWDA 2025 State Budget Update #1 - Governor’s Proposed 2025-26 Budget

- LAO The 2024‑25 Budget In-Home Supportive Services

- Wested, California Special Education Funding System Study, Part 1

California’s Budget

A state’s budget is mostly funded by state income tax, including capital gains, corporate tax and sales tax. Notably, state revenue can be volatile because about half the state receipts come from just the top 1% of earners, and their income is dependent on the stock market.

Source: California eBudget

Federal Medicaid

Medicaid is a federal government program to support families with limited resources that has existed since 1965. It was significantly expanded in 2010 by the Affordable Care Act (sometimes called “Obamacare”). Nationally, Medicaid provides free health insurance to 85 million low-income and disabled people as of 2022. Medicaid also pays for long-term services and supports, such as nursing home care and home and community-based services, for those with low incomes and minimal assets. Each state has a different set of rules about who qualifies and what services it can be used for.

The Social Security Act of 1981, signed into law by President Reagan, created the Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) Waiver program, section 1915(c). The legislation allows California to offer services other than healthcare that are not part of the regular Medi-Cal program to serve individuals with developmental disabilities in their own homes and communities. If it were not for the HCBS Waiver program, many individuals would be at risk of being placed in institutions rather than being cared for in their homes and communities. The waiver supports independence and family and community living while costing less than institutional care.

Although it is a federal program, Medicaid shares costs with the states. The federal government sets some rules about who is eligible and how it can be used, but the states run the program, and providers receive reimbursements from the federal government. The total annual cost of Medicaid nationally is over $600 billion, of which the federal government contributes $375 billion and states an additional $230 billion.

Medi-Cal

In California, the Medicaid program is the California Medical Assistance Program, also called Medi-Cal. California uses Medi-Cal more than most states, taking full advantage of the expansion to offer free health care to low-income individuals, including families, seniors, children and adults with disabilities, children in foster care, pregnant women, and childless adults with incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level. Approximately 14.8 million people were enrolled in Medi-Cal as of December 2024, or about 38% of California's population. About 58% of children in California rely on Medi-Cal.

The current HCBS Waiver program was approved by Medi–Cal in 2024 for five years to cover up to 179,000 individuals by December 31, 2027. (There are 465,165 Regional Center consumers, of which 54% are children.) The HCBA Waiver program has a much smaller cap (7,200 slots), which is typically reached, so there is a waitlist before individuals can get covered.

The California State Budget pays for part of Medi-Cal. The enacted 2024‑25 budget provides $161 billion for Medi-Cal. Roughly half of this comes from federal Medicaid reimbursement, and the remaining is covered by the state. California puts $35 billion in from the General Fund—roughly 17% of total General Fund spending.

The federal portion of Medi-Cal is determined by a formula called the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), which varies based on the type of enrollee (e.g., Affordable Care Act expansion population) and other criteria determined by federal law. California’s FMAP is generally 50%, meaning the federal government pays half of the cost of providing coverage to an enrollee, with no preset spending limit. However, for some services, the federal government pays more. In 2022, Federal Medicaid contributed 70% to Medi-Cal, 21% came from the California general fund, and 9% came from other state and county funds.

The Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) expects Medi-Cal costs to continue growing because provider rates will continue to grow and more people will become eligible (see their chart below). They project $48.8 billion will be needed from the general fund to support Medi-Cal in 2028‑29, a $13.8 billion (39%) increase over the enacted 2024‑25 level — an average annual rate of growth of 8.6%.

California Department of Developmental Services (DDS)

Most of our children’s services are provided by the California Department of Developmental Services (DDS). They provide the grants and reimbursements to Regional Centers that are used to fund Regional Center services, both traditional and Self-Determination Program.

DDS coordinates a wide variety of services for more than 450,000 Californians with intellectual or developmental disabilities or similar conditions, mostly authorized by the Lanterman Act. DDS also covers Early Start for toddlers with developmental delays under Part C of IDEA. In addition to federal law, the California Early Intervention Services Act ensures services for eligible infants and toddlers. Early Start is also provided through SELPA funded in part by the California Department of Education.

Regional Centers

DDS contracts with the twenty-one Regional Centers across California, which coordinate and pay for the direct services provided to “consumers.” Some of this money comes from the General Fund and some smaller funding sources. Services are also purchased through federal funding obtained through the Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) waiver that provides Medicaid funding for eligible individuals to receive services and supports in their home and community-based settings, rather than in institutions.

Although DDS is a state agency, it uses federal Medicaid reimbursements to provide funding for its services to eligible consumers. In fiscal year 2024-25, California plans to spend $15.3 billion on Regional Center services. $10 billion is from the General Fund, an increase of almost $2 billion. About $10 billion will come from federal reimbursement, $5 billion will come from the federal Medicaid and $56 million will come from federal Early Start Part C of IDEA.

DDS itself spends $315 million on state-operated services, 10% of which is reimbursed by federal dollars, and $160 million on their headquarters supporting both regional center and state-operated services, of which $54 million is reimbursed.

In order to pay for their $15.8 billion budget, DDS receives reimbursements from federal grants including $5 billion from Medicaid federal funding, which includes $3.7 billion from the Home and Community-Based Services Waiver and $11 million from the Self-Determination Program Waiver. This $5 billion also includes $136 million under Title XX federal block grants and $77 million from federally funded TANF block grants.

In 2016, the state conducted a rate study explaining that the reimbursement rates to providers for Regional Center services were at a breaking point and needed to be increased. The state planned a steady rate increase over five years that would gradually bring the provider rates up to where they need to be. However, in the current economic outlook, the governor instead decided in the 2025-26 budget to put these increases on hold and use this $600 million to plug the hole in his deficit budget.

If you are an SDP consumer (around 6,000 families), the program is expected to spend $498 million this year and grow to almost 9,000 families next year and cost $780 million. $210 million is expected to be provided by federal funding, and $325 million next year.

IHSS

In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) doesn't just cover children with disabilities; the program also provides personal care to low-income elderly, blind, or disabled adults to help them remain safely in their own homes and communities. The governor projects that an estimated 691,075 IHSS recipients in California will receive an average of 123 IHSS hours per month in fiscal year 2024-25.

IHSS costs are shared by the federal government, state, and counties. The federal share of costs is determined by the Medicaid reimbursement rate, which typically is 50%. The state receives an enhanced federal reimbursement rate for many IHSS recipients who receive services as a result of the Affordable Care Act expansion (90% federal reimbursement rate) and the Community First Choice Option waiver (56% federal reimbursement rate). The effective federal reimbursement rate for IHSS is 54%.

The county's share is a bit complicated. Before 2012-13, counties paid for 35% of the nonfederal share of IHSS service costs and 30% of the nonfederal share of IHSS administrative costs. The share-of-cost model was then replaced with a maintenance-of-effort (MOE) model, meaning county costs reflect a set amount of nonfederal IHSS costs as opposed to a certain percentage of nonfederal IHSS costs. The state is responsible for covering the remaining nonfederal share of costs not covered by the IHSS county MOE.

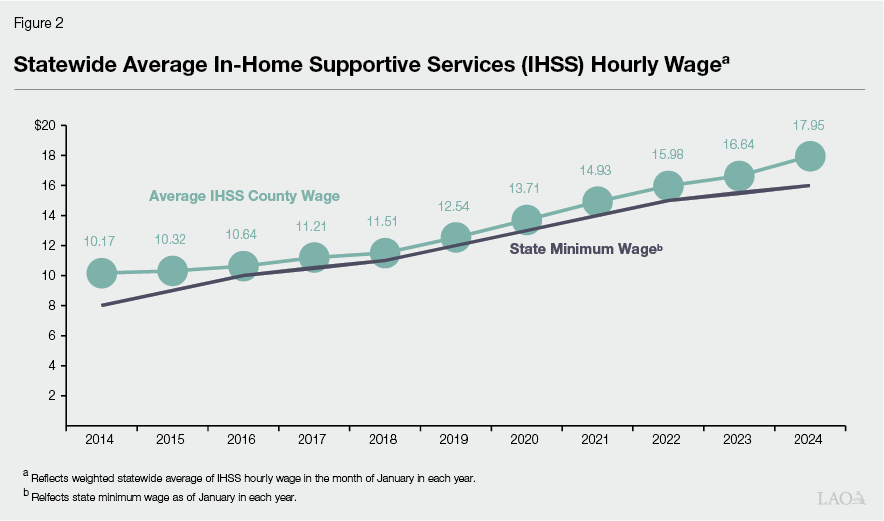

The California state budget includes $24.3 billion ($9 billion General Fund) for the IHSS program in 2024-25 to cover almost 700,000 recipients. The Governor anticipates that IHSS costs will continue year-to-year growth based on increases in provider wages, case loads, and administration costs. Case loads increased as more people became eligible for Medi-Cal due to the asset limit being lifted between 2022 and 2026, and service providers wages per hour have grown. The average IHSS hourly wage has increased by six percent annually since 2014 and is expected to increase to $20.52 in 2024-25. For caseload growth, the 2024-25 budget assumes the caseload will grow at around 4.6 percent.

Source: LAO

The County Welfare Directors Association of California (CWDA) is requesting $51 million in one-time State General Fund (SGF) to address the underfunding of social worker and related staffing costs in the IHSS program for the 2025-26 budget. CWDA is also requesting trailer bill language requiring the California Department of Social Services (CDSS) to work with CWDA and counties to update the existing IHSS administration budget methodology to take effect in FY 2025-26. Los Angeles County spent $931 million on IHSS in 2023-24 and is asking for $15 million one-time from the State.

Each county is primarily funded from property taxes. A small amount comes from sales tax.

Special Education Funding

Although special education is created by a federal law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), very little funding for special education comes from federal sources.

In most states, education is paid for by local property taxes, which are relatively stable. In California, where property taxes are limited, the state supplements property taxes for most districts with funds that come from state income taxes, capital gains tax, and sales taxes, which depend heavily on the state of the economy, especially the fortunes of the most wealthy residents.

Local school districts are primarily funded by the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). This formula allocates funding to the districts by topping up local property taxes to ensure that the quality of education isn't dependent on local property values. The funding is allocated based on Average Daily Attendance (ADA), the number of kids who show up to school each day. The LCFF also allocates supplementary funds based on the number of children who live in poverty, are foster kids, or are English language learners. This funding goes into the school district's general fund, and the Board of Education determines how it is spent through the Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP).

Schools get some state funding for special education through a system called AB602. Funding is not based on the number of students with IEPs. The money is distributed to districts through Special Education Local Planning Areas (SELPAs) based on total student attendance (ADA). In multi-district SELPAs, different formulas decide how the funds are split among districts, sometimes taking into account numbers of IEPs and high-needs students. There’s also extra state funding for low-incidence students with specific disabilities, like visual impairments (VI), deafness or hearing loss (DHH), and other qualifying conditions.

However, state funding covered only about 10.8% of special education costs in 2019, with most of that coming from AB602. Since then, the state has increased its share by over $1 billion between 2019 and 2022—about a 30% increase beyond normal cost-of-living and attendance adjustments. The base funding per student (ADA) went from $557 in 2019-20 to more than $820 in 2022-23.

The federal government also provides grants to the states under IDEA. When the law was originally passed, the proposal was that the federal government would give the states 40% of the average cost of public education per student with an IEP. However, in reality, the federal funding has never exceeded 18% of this figure. Since the formula is based on a census of students with disabilities in public and private schools in 1990, and since the cost of special education is probably more like 2.5 times the average cost of public education, this federal funding rarely amounts to more than 10% of spending on special education in California.

Source: California Special Education Funding System Study, Part 1

Medicaid can also be used by districts to fund related services in special education if a parent gives permission. You may have seen this checkbox on your IEP. Reimbursement would allow the school to collect 50% of the cost from federal Medicaid dollars. In reality, schools underuse this funding stream due to the administrative burden of collecting it.

Spending on education in California is guaranteed by Prop 98, which says that the state must spend at least 40%, and sometimes more, on our public education system. However, this funding is allocated by ADA, (apart from a few wealthy Basic Aid districts) and many districts are experiencing falling enrollment, so their state allocation of dollars is falling, and districts experience reduced revenue even if the base rate is stable.

Federal Grants

A number of our California community resources are also funded by grants from the federal government, particularly Parent and Training Information Centers such as TASK and DREDF. Most of these community supports also receive state funding as Family Empowerment Centers or Family Resource Centers 0-5.

Many families in our community are worried about reductions in federal funding. California offers many programs that other states do not offer, but we should be aware that the state, already planning a deficit budget, will not be able to fill the gap if the federal Medicaid funding goes away.

Chris Arroyo, Deputy Director of Policy and Public Affairs at the California State Council on Developmental Disabilities, told us:

“The proposed funding cuts would have devastating consequences for Californians, as the state would struggle to make up for the loss of federal funding. Programs like Regional Centers, Medi-Cal, In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS), Covered California, Women Infants and Children, CalFresh, and more all rely on Medicaid dollars to provide essential services to millions of residents. Without these funds, the state would face impossible choices—either drastically reducing services for recipients or shifting an enormous financial burden into an already strained state budget. The reality is that California simply cannot replace this level of funding, and the impact on individuals, families, and communities would be profound.”

Sources:

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor