Supporting Our Children’s Behavior at School

Many of us are familiar with school-wide positive behavioral programs that focus on values such as respect, kindness, and hard work and reward students when their behavior reflects those values. But how do these programs include children with disabilities, particularly those with extensive behavior and/or support needs in general education environments? When can school-wide interventions be modified?

How can parents get behavior supports at school for their child?

Education advocate Dr. Sarah Pelangka explains that it’s based on the needs of the child. “Behavior supports come in many forms,” she says, “such as behavior strategies (e.g. embedding visual supports, checklists, token systems self-monitoring checklists, organization systems, etc), incorporating home-school communication logs to align home and school, adding in behavior goals, adding in a behavior plan, adding in behavior intervention services (this takes the form of the school behavior team consulting and collaborating with the student’s team), completing a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA), adding in a behavior aide with behavior supervision from the school BCBA, etc.”

Dr. Caitlin Solone, education advocate and academic administrator for the Disability Studies program at UCLA, discusses the importance of behavior support for children with disabilities seeking inclusion in school and stresses that a child's behaviors are a means for communication.

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS)

A Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) program is often used in schools to help encourage good student behavior. In a school setting, PBIS is an evidence-based practice for reinforcing students' good behavior. PBIS is not a one-size-fits-all system but an approach that helps reduce problematic behavior and build relationships between students and teachers. PBIS involves establishing expectations for students, teaching students what those expectations are, and rewarding them when they meet those expectations to build a positive reinforcement system. Because students benefit from consistency, PBIS is implemented throughout an entire school rather than in only one classroom.

Dr. Sally Burton-Hoyle, professor, ASD Area, and faculty advisor in the Department of Special Education College Supports Program at Eastern Michigan University, tells us that when she’s in special education classrooms and a child has displayed a behavior such as getting angry and knocking all the books off a shelf, she’ll ask the teacher if the child knew what the expectation was of them, and how. Typically, a teacher will express expectations verbally, but often, other methods can be more effective, such as having visual representations or Social Stories.

“I'm going to guess that 90% of the time, when children are acting up, [expectations weren’t] made clear to them,” Dr. Burton-Hoyle says. “A part of positive behavioral support is making sure that people have the expected outcomes ahead of time, and that it isn't a surprise to them. And I don't understand people who put kids with disabilities in this kind of situation… When you instruct kids and they don't understand what they're supposed to do, they're going to do something challenging.”

You can also think about using the Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports strategies at home and making a PBIS home plan. “When you teach your child the same behaviors that are taught at school and reinforce them at home, you are encouraging your child’s social and academic growth,” the PACER center explains.

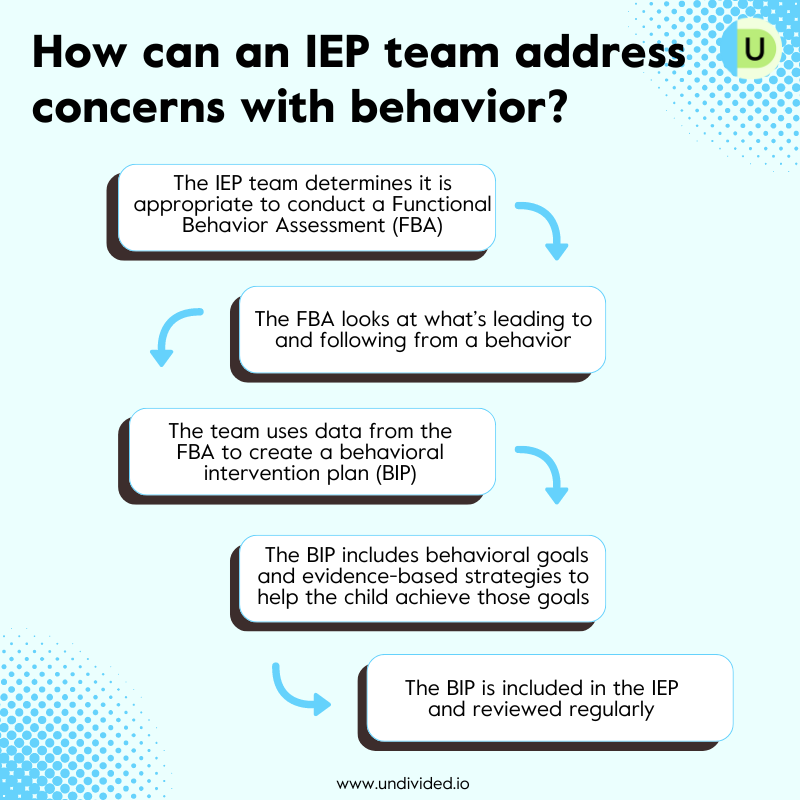

Functional Behavior Assessments (FBA) and Behavior Intervention Plans (BIP)

One of the primary ways to address your child’s behaviors is through an assessment. According to Rose Griffin, speech language pathologist, Board Certified Behavior Analyst, and founder of ABA Speech, “Whatever avenue you're going, so if you're doing Floortime, you're doing ABA, you're doing speech therapy — I think what's most important is that we start with an assessment so we can kind of see where is the student? And then where are the strengths? Where are the areas that we need to support our students? What does that support look like? And just making sure that providers are going to be really detailed with that plan, and how that plan is going along the way. You don't want to just set the plan and forget the plan and think that everything is going to happen, right? Because it's not that easy. So I think just having that general framework, and if you're working with a provider that doesn't do those things, then that might be another red flag as well.”

A Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA), which is often (but not always) conducted by a BCBA, is an assessment that you discuss with your IEP team. Note that in the state of California, a BCBA is not a legal requirement for FBA completion; an FBA can be completed by a school psychologist and even a SPED teacher.

An FBA looks at what’s leading to and following a behavior in order to develop a behavioral intervention plan (BIP), which then gets included in the IEP.

Dr. Pelangka explains, “Within the educational setting, a behavior intervention plan (BIP) is a written plan designed to support school staff in knowing how to set up the student's environment to allow for success and independence, communicate strategies to help proactively prevent behaviors form occurring, and communicate reactive strategies so all staff are consistent in how behaviors are responded to.” It also includes behavioral goals and evidence-based strategies to help the child achieve those goals. FBAs can be conducted when the IEP team determines it would be appropriate for the child, or when a change in placement is being sought due to behaviors. Once an FBA is requested, the district has fifteen days to provide you with an assessment plan. Once that is signed and returned, the district then has sixty days to conduct the FBA and hold an IEP meeting to discuss it.

Dr. Pelangka tells us, “An FBA is an assessment that essentially looks at the student’s immediate environment via direct observation. Through the FBA, the assessor hypothesizes what may be contributing to any problem behaviors the student may have. The FBA should also incorporate interview data, adaptive skills assessment (to rule out skill deficits), and a comprehensive records review, to again rule out skill deficits.” She adds that, “It’s not true that only ‘dangerous’ behaviors warrant an FBA (as is often communicated to parents). Behaviors that are occurring at high rates or for long durations that impede the student’s ability to learn can warrant an FBA.”

Dr. Burton-Hoyle explains how FBAs can help get to the “why” of a problem, and how parents can advocate for the school to do more thorough FBAs of their child:

What happens after an FBA? Dr. Pelangka explains that the outcome of an FBA may include recommendations, such as:

- A high level BIP (Tier 3 or Comprehensive Behavior Plan)

- A low level BIP (Tier 2 or Positive Behavior Plan)

- No BIP and maybe recommendations for other strategies/environmental adaptations, services, etc.

Low-level BIPs don’t require an FBA, she tells us, and can be written by the IEP team collaboratively. The team would go through the BIP section by section and develop a plan that they believe will best meet the needs of the student. Ideally, there would be data to work off of to create the BIP, but if not, the team can suggest going back to collect data, or they can agree that there is a need and data will be collected moving forward. Any Tier 3 or Comprehensive Behavior Plan does require an FBA, however.

Dr. Pelangka adds that parents should be aware that the FBA assessors do not deem skill deficits to be maladaptive in nature (maladaptive behaviors are those that the student can control). For example, a student might have a learning disability in the area of orthographic processing, which directly impacts writing. “If the maladaptive behavior found is that a student engages in work refusal during writing tasks,” she says, “we shouldn’t be writing a behavior goal for the student to ‘complete writing tasks’ or ‘ask for a break during writing tasks.’ We should be focusing on what tools the student has to access writing, given they have a learning disability in the area of writing (e.g., assistive technology tools, access to a scribe, etc.).”

Request a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA)

Let’s talk behavioral IEP goals

When schools write IEPs, goals around behavior may be compliance-based, such as reducing a certain behavior that is deemed challenging or problematic. But as Dr. Burton-Hoyle tells us, IEP goals should not be about reducing “unwanted” or “bad” behaviors but perhaps replacing them with more functional behaviors. “Let's talk about their needs,” she says. For example, “Instead of [focusing on reducing the] banging the head, what should that child be doing? Maybe playing with other kids? That's the positive behavioral support [approach]. Then banging his head: what does it mean? That means he's frustrated or it means he's lonely. Then the goal is around that, not reducing something.”

For many kids with developmental disabilities, IEP goals can actually promote masking their traits and behaviors in an attempt to “normalize” or “reduce” their behavior, which may be inherent to who the are, how they process sensory stimuli, and how they communicate (for example, goals for more eye contact, tone policing for appropriate responses, constantly initiating conversations, etc.). Certain goals can set up children for manipulation, exploitation, and bullying. Many of these goals have the word “appropriate” in them — as in “appropriately respond” or “appropriately acknowledge” — and may be expected even when a child is being teased or bullied.

Dr. Greene tells us, “Compliance, and our obsession with it, is at the root of a lot of big issues that are not going well. I don't think that the goals of an IEP should be translated as behavior most of the time. I think unsolved problems should be the goals of the IEP. That's what we're working on.”

IEP goals that center the unsolved problems can work toward supporting a child in building skills and interests that allow them to grow beyond the behaviors. Creating strengths-based goals instead of decreasing non-compliance can look like increasing skills such as communication, negotiation, compromise, “no” responses, and problem-solving.

Breea Rosas, school psychologist and founder of Neurodiversity Affirming School Psychologist, explains that neurodiversity-affirming goals focus on things like regulation, self-advocacy, and what the child wants. Because of this, “The goals are going to be better and the accommodations are going to be better because when you're a neurodiversity-affirming provider, you're going into the classroom and you're looking at what things are supporting this child right now, and what things are not working. So you can make a really solid IEP because you're not just looking at [a kid] moving around a lot, you're looking at, ‘Huh, this kid likes to stand while they're working, that's an accommodation we're going to put in their IEP. They are fiddling with things on their desk, let's get them some fidget tools — that's a great accommodation for their IEP.’”

Dr. Pelangka shares that goals shouldn’t be aimed at trying to change the person but to support them in what they actually desire for themselves. For example, it’s not necessary to establish goals for more eye contact. It can be overstimulating for their brains, it depends on the culture, and individuals can show that they are engaged in other ways (e.g., remaining in the area, facing the direction of a communicative partner, responding with related responses, etc.). “We should aim to give them the tools to have meaningful and positive social experiences,” she says.

For more information about writing behavior goals in the IEP, including example goals, see our full article Behavior Goals in the IEP.

What can we do to ensure our child’s BIP isn’t focused on “compliance?”

Dr. Pelangka tells us, “Given the influx of self-advocates who have come out and shared their stories on ABA (and how detrimental it’s been to them), I firmly believe it is imperative that we, as behaviorists, do a better job. The goal should not be aiming for “compliance,” but rather, the goal should be aiming for acceptance. What I mean by that is the students' acceptance of the adult (teacher), the classroom, and the content being taught.” What does this look like? She gives us three examples:

Building and establishing rapport and trust with the student (acceptance of the teacher/adult).

Ensuring the classroom is a safe space for the student. This can be accomplished by embedding things that support the student (e.g. dim lighting, headphones, fidgets, preferred visuals on walls, etc.) and being willing to modify the room on an ongoing basis to meet the needs of the student (for example, if the classroom gets too loud).

Teaching to their level and ensuring access by way of accommodations and services. The student should have all of the services and supports they need to be most successful. “This sounds like a ‘duh,’” she says, “but I can’t tell you how many parents I come across who don’t even know they can ask for an assistive technology assessment for access to curriculum, not for AAC purposes. Or counseling, or recreation and leisure, etc. There are so many things accessible to students; they should be offered when needed.”

How to advocate for your child at school

Another thing to consider is that students with disabilities can often face harsh and exclusionary disciplinary action at school around behavior. The Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires school teams to use positive behavior interventions when supporting students who receive special education services with their behavior and social and emotional development. Dr. Pelangka recommends that parents hold the school accountable by discussing behavioral interventions during their IEP meetings.

What else can you do to protect your child? What does all of the above information mean for you and your child?

- Review your child’s IEP (or 504) to make sure it includes a behavior intervention plan as well as supports and services to minimize disruptive behavior in their current placement. If these aren’t in place or they aren’t sufficient, request an IEP meeting.

- Save data in your binder about your child’s behavior at home and in the community. This could include reports from in-home behavioral specialists or your own notes about what triggers certain behaviors. This data will be useful when working with your IEP team and if you’re asked to attend an FBA.

- Learn about positive behavior interventions and supports (PBIS) in place at your child’s school by talking to teachers and other school leadership. Our article about PBIS has sample questions you can ask. Dr. Solone also explains more about behavior and PBIS in this video clip.

Free resources

The Association of University Centers on Disabilities (AUCD) has also shared that The Vanderbilt Kennedy Center (VKC) has created two new toolkits on cognitive behavioral strategies for autistic students. The toolkits are intended for educators and school teams (IEP teams) working with both students in elementary school settings and adolescent students. This could include teachers, school staff, administrators, paraeducators, school psychologists, and others working with autistic students and students with developmental disabilities. Find both toolkits here and share with your child's school team.

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor