Behavior 101

As parents of children with disabilities, trying to support our kids through challenging behaviors — and sticking to the behavior plans and behavior goals that our therapists, doctors, and behaviorists create — can almost feel like learning and translating a foreign language. Many of our children don’t have the words to tell us what they’re feeling or what’s bothering them, and even if they do, they likely don’t even know the “why.” This can make any parent feel frustrated and completely powerless. And guess what? Our children feel the same way.

While every child is different, learning how to “translate” a behavior, and reframe the way we view behavioral challenges in kids with disabilities, can not only help us find the most appropriate approach to managing behavior, but it can also help us get to the root of what’s happening to help our kids regulate so they don’t have to exhibit the behavior, whatever it might be, or find different ways to communicate their needs. But there are so many ways to view behavior, and many different approaches, interventions, theories, and therapies — many of which even seem to contradict each other. Not everything is going to work for every child, so how do we navigate and land on something that is the right fit for the unique needs of our children, and still feels empowering, healthy, and within our value system? Where do we even start?

To get more insights on the different approaches to behavior, plus tips for parents about managing behavior in school, at home, and in the community, we spoke to several experts in behavior, special education, and psychology.

Getting to the root of behavior

As parents, dealing with behavior challenges may be one of the most frustrating and urgent things to navigate, whether at home or at school. But understanding why children with disabilities have challenging behaviors is the key to providing intervention. Is there such a thing as “bad behavior?” According to the experts we spoke to, a behavior is a symptom of something deeper. A child is not simply “behaving badly” because they want to. So while addressing a specific behavior may help in the moment, it’s often not a long-term, meaningful, or holistic solution to helping our kids feel better.

All behaviors occur for a reason; it’s up to us to figure out what that underlying reason is, and there are many approaches. Let’s explore the different reasons behind challenging behavior in kids with disabilities.

Behavior as a form of communication

First of all, we can start by thinking of behavior as a form of communication. We all communicate through our behavior in one way or another. An infant cries when they’re hungry, we may pull away from a person if we’re feeling unsafe, etc. While those may not be “bad behaviors,” a child exhibiting challenging behavior is also trying to communicate something, and they may not have the skills to do so in another way.

Dr. Sally Burton-Hoyle, professor, ASD Area, and faculty advisor in the Department of Special Education College Supports Program at Eastern Michigan University, explains challenging behaviors often occur in kids with disabilities when they don’t have another way to express what they are feeling. Even if a child has a large vocabulary, they may not be able to access the right word to express how they feel, or retrieve the words quickly.

This mindset shift considers why a child is exhibiting challenging behaviors and allows educators, providers, and parents to consider what a child is trying to tell us through a behavior and what the unsolved problem is. Especially for non-speaking children whose behavior may be the only way they can communicate, they might be trying to tell us that they’re uncomfortable or scared. Maybe they’re trying to avoid or escape an undesirable experience, sensory feeling, or interaction. When school staff, parents, providers, or therapists don’t understand a behavior or know how to respond to a child with a disability who has challenging behaviors, that child may be placed in more restrictive settings, or be inappropriately disciplined.

What are our kids telling us?

For Dr. Ross Greene, clinical psychologist and the author of The Explosive Child, Lost at School, Lost and Found, and Raising Human Beings, it isn't always obvious from the challenging behavior what the problem is. Parents have to think beyond the immediate behavior and identify the unsolved problem. “All non-speaking kids are communicating. How are we doing it, using our eyes, to figure out what they're trying to tell us? How predictable is what they're telling us? Because we shouldn't be surprised every single time. And how can we collaborate with them on addressing some of those things?” (More on Dr. Greene’s approach later!)

Dr. Burton-Hoyle shares that when behavior is not viewed as communication, the child can often be blamed for the behavior, or even called “manipulative” when there is a clear reason why they are behaving the way they are. She recommends visual supports, such as task lists and charts. Parents may create a chart that first lists the expectations for the situation. If it doesn’t happen in the way they planned they should look at what happened in the situation, then what typically happens in that situation, then what was different. “Otherwise, you may blame the child, when it was absolutely not the child’s fault.. I am always triggered by the use of the word ‘manipulative’ [but] are we accounting for neurological, sensory, or environmental needs [of that child]? All those sorts of things? Are we dealing with them?”

How can parents learn the “why” & support communication?

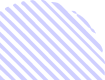

Dr. Burton-Hoyle tells parents that a child having behaviors can even be a good thing: “I always tell parents to say, ‘Yay, good, I'm glad they're having behaviors,’ because then they're letting you know what and how they're feeling about things. I really want parents, to try to figure out how and why. What happened? What typically would happen? And what was missing?” This approach can help parents understand and put into action a different plan the next time. What are some ways to reframe behavior as communication? She shares that parents can presume competence, identify strengths, give choice and control, and look for environmental/sensory barriers.

Something parents can do is try to learn their child’s language — how they communicate. Focusing on the relationship between parent and child is vital. Dr. Scott Akins, chief of developmental behavioral pediatrics UC Davis, Department of Pediatrics and medical director at the UC Davis MIND Institute, explains that parents can help kids build skills and expand out their frustration tolerance, whether it’s finding ways to help them through transitions, going to the doctor, etc. He adds that it’s important to find time outside of a child’s dysregulated state to build relationships and skills.

Dr. Burton-Hoyle tells us that another way parents can learn their child’s behavior language is to create a behavior dictionary: every time your child does something, you can write down what it means. Even if you just suspect or are unsure, try your best to document what your child is doing or saying, or what you think it might mean.

Parents can also work on getting a communication system in place for kids who are non-speaking, even if it's something they hadn’t considered before like an augmentative communication device (AAC) or sign language, which can really help with frustration tolerance. Working with a speech therapist may also help build on those communication skills for all kids, speaking and non-speaking.

All behavior has a function: a functional-based approach

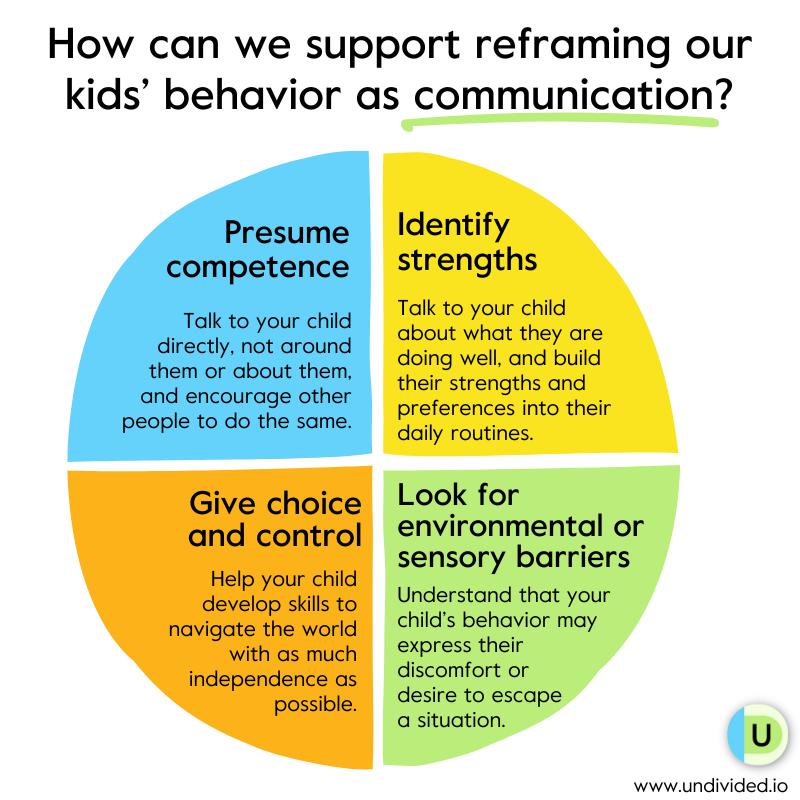

A functional-based approach to behavior is based on “operant conditioning that describes the relationship between antecedents (such as settings), behaviors, and consequences.” The functions of behavior fall into four different categories: attention, escape/avoidance, access to tangibles, and sensory stimulation. These functions are often used in schools when doing a functional behavior assessment and commonly in behavioral methodology including applied behavior analysis (ABA).

Dr. Sarah Pelangka, BCBA-D and education advocate, notes that we should also understand that while there could be a function of a behavior, such as to escape, “assessors need to delve deeper — escape from what? Also, behaviorists need to start recognizing there are internal states. Many students are escaping embarrassment, shame, etc. Trauma is a major factor for many students. Go beyond the surface-level functions. Access — to what? Attention — from whom and why?”

Many times, kids do have some foundational skills around joint attention, shared affect, and language, but they're frustrated because they're working hard to communicate, but are not very successful at it. Building those communication skills can help decrease some of that frustration and increase their engagement.

Rose Griffin, speech language pathologist, Board Certified Behavior Analyst, and founder of ABA Speech, explains that behavior is often an issue with trying to communicate these needs: “Oftentimes, students who have any type of communication impairment or have needs in the area of communication may use their behavior to kind of navigate their environment or navigate their day. Some of our learners are not yet verbal or they don’t have a device or pictures, and so they're really just trying to get their needs and wants met and navigate life. And so if you're not able to do that verbally, you may do that through sometimes unsafe problem behavior.”

Dr. Akins tells us that one function could be that a child is dysregulated and can't settle down, or for some neurodivergent children, it might be something sensory related, such as a smell that bothers them, or memories of a bad experience in a specific location, like a doctor’s office. “And so you get a child that's pacing, is loud, using a lot of vocal self-stimulatory behaviors, and maybe a lot of hand-finger stereotypies, and looks really agitated. And for me, that’s a classic example of the function of that behavior being ‘something happened to me last time and I'm scared.’ That's part of why this idea of using a timeout or something like that for that kind of behavior just doesn't make any sense. We really have to help with coping skills.”

Dr. Akins continues, “It might mean that the solution for that is to go out for five minutes and then we'll start again. It might be that next time you come, if it was a clinic visit, that we show you a visual story of your visit to the clinic. And over time, when we look into the visual story, we realize that getting your vitals is very dysregulating for you, so we cover that piece up and communicate that to you on the way in, so we know that you're not going to get a blood pressure cuff or whatever it is that might upset you. It might be that we need to add some sensory diet items like squeezy balls and other things to help you regulate in a high-stress setting. But yeah, it's a function; I want to figure out what the function of a behavior is.”

The ABCs of behavior

Many parents and educators have been trained to analyze challenging behavior by looking at the antecedent and the consequence — as Dr. Akins explained — to understand the function of the behavior. And while this is important, especially when assessing a child and creating behavior goals, a good approach to behavior is not one strategy to fix the problem; it’s whole-child based and holistic.

He explains more about how we view and approach behavioral challenges has shifted over the years, and how he thinks about behavior in terms of regulation and skills-building:

Both individual and global

Looking at behavior functionally means that we have to look at it at an individual level as well as a holistic, global level — the environment. Griffin explains why it’s important to individualize function when approaching behavior challenges:

Behavior as a result of lagging skills

Dr. Greene shares with us a different perspective to understanding and addressing challenging behaviors, and they don’t involve functions or ABCs. Dr. Greene’s Collaborative & Proactive Solutions (CPS) model emphasizes empathy, collaboration, and problem-solving rather than traditional motivation-based approaches, such a ABA (more on this later!).

Dr. Greene says, “Kids do well if they can,” meaning that challenging behaviors are a result of lagging skills rather than lack of motivation to be good. “Kids who exhibit concerning behaviors are often struggling with some very important skills. And I've grouped those skills as flexibility, adaptability, frustration, tolerance, problem solving, and emotion regulation. Kids with disabilities are not a monolith. Obviously, they represent many, many different issues and different profiles. But many kids with disabilities are more prone to be struggling with the skills that I just named and/or also have more expectations that they're having difficulty meeting by virtue of their disability,” he explains.

The CPS model focuses on identifying and addressing the underlying problems or "difficulties meeting expectations" that lead to these behaviors, rather than simply reacting to the behaviors themselves.

The brain-behavior connection

Dr. David Stein, PsyD, pediatric psychologist, adds that learning about brain science can also help in understanding behavior. One example is for kids with ADHD, where there is inattention as well as hyperactivity and impulsivity. “People really have a hard time understanding problems with impulse control, which is kind of a core feature of ADHD. So I have a lot of parents who tell me, ‘My child with ADHD just doesn't care, and we've told her 1000 times don't hit or don't run into the street, or what have you, and she just doesn't care and does it anyway.’ So what people have a hard time understanding is that in that scenario, in a situation of a child with ADHD, it's not that the child doesn't care, it's that when that situation arises, if you don't have control of your impulses, even though you know better, you're still going to do the thing that you shouldn't do. So in this situation, working with a child and teaching them how to ‘behave’ may not work because it won’t change the underlying issue, which is that the child may know what the right response or behavior is, but when a situation arises, impulses take over.”

This is why managing behavior has to take into account developmental stages, age, diagnosis, etc. Dr. Stein tells us that for kids with ADHD, psychotherapy is not an evidence-based intervention because it just doesn’t help with things like impulse control. However, medication can help, if that’s the route you choose to take, and behavior therapy can help because it sets up structures to help kids do their best.

Dr. Sally Burton-Hoyle also tells us, “Anytime you have a neurological condition, whether it's learning disabilities, or Down syndrome, or autism, or cerebral palsy, it impacts that whole process of listening to people. The auditory processing may be the weakest link and is important for parents and caregivers to understand when somebody says something to you, you have to first comprehend and figure out, ‘What does that mean?’ Then you have to retrieve the information then translate it into appropriate words… When children misbehave or act out, usually there's been some kind of verbal/auditory direction or command, and they're expected to be compliant right in that instant. And neurologically speaking, that's sort of impossible. Then when it doesn't happen quick enough, then that person feels stressed and gets upset.”

What does “non-compliance” actually mean?

As a parent of a child with a disability, chances are that you’ve heard the term “non-compliant.” The topic of “compliance” and “non-compliance” when it comes to our kids’ behavior is extremely important to address, although controversial, because it’s not only about managing behavior but also autonomy.

Compliance simply means that we follow a rule or do what someone tells us to do. While it’s helpful for a child to learn to follow directions, participate with peers, keep to the schedule, follow classroom rules, etc., it doesn’t always look the same for kids with disabilities as it does for typical children. In fact, it can sometimes cross the line of being dangerous if a child is being conditioned to comply and listen no matter what while ignoring their own instincts and feelings.

Autonomy and keeping kids safe

Dr. Burton-Hoyle tells us that the term “non-compliant” is overused by providers and therapists, and it can be very hurtful to kids when people tell them they’re non-compliant because, over time, it can create a sense of low self-worth or a lack of skills or language to keep themselves safe.

A report by The Autistic Self Advocacy Network explores how “non-compliance – and the ability to evaluate situations and decide when it is safer to refuse to comply – is a fundamental life skill” and that the same behaviors that are encouraged in typical children as safety mechanisms such as stranger danger “are pathologized as ‘non-compliance’ in kids with disabilities, which teaches them that their ‘no’ is meaningless and that our bodies are not their own.”

Teaching children to comply can become dangerous if we don’t also teach them about boundaries and personal safety, especially for kids who may not be aware that they are being manipulated, harassed, or taken advantage of. For more information on this, see the work of author and certified sex educator Terri Couwenhoven, MS, CSE, who specializes in personal safety and sexuality for people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities and their families.

“[We need to] teach kids how to use language, or symbols, or hand motions to get people away from them if they're not feeling safe,” Dr. Burton-Hoyle says. “Every child should feel safe wherever they are, whether they're at home, or they're at school. If they're not feeling safe, if we've had this system teaching them to do whatever people say, we're going to have way more vulnerable people that have been molested, or violated in some way. We need to teach kids how to assertively use words or actions to speak out. And whether it's, ‘Ah,’ or, ‘Ugh,’ it doesn't matter. The focus doesn't need to be on the words, because the words, when you have neurological issues, are hard to retrieve. We must instill in our girls, especially, that we have confidence in them and that we trust them. I think it's one of those things at their core, they need to feel valued.”

Helping kids advocate for their needs

Self-advocacy plays an important part here, especially if a child is refusing a task or not complying because they are trying to advocate for a need, like a break or a drink of water, or expressing preferences.

This approach centers a child’s voice and respects their autonomy and self-determination. For example, if a teacher tells you that your child is not turning their work in, you should ask them, ‘Do you know why they're not?’ Sometimes, a teacher may just say, ‘They're just choosing not to.’ That's where a Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA) can be really helpful, Dr. Burton-Hoyle explains. Maybe the child isn’t following the rules or ‘complying’ because they need more accommodations such as visual supports. When we do not recognize the needs, then family or teachers may treat the task not being completed as non-compliance. Maybe it is important to recognize the impact of the environment on their behavior so their sensory needs could be addressed through a sensory diet. This type of plan should be designed by an occupational therapist and may include short activities such as wall push ups or adaptive seating. So the question should be: what does that child need? Then, these needs can be explored and addressed through a behavioral assessment, sensory plan, IEP goals, and a behavior plan that actually helps the child feel more in control, self-expressed, and capable.

Dr. Burton-Hoyle adds that “non-compliance” can also simply mean that a child doesn’t know what the expectations are for a certain activity or event. Or that the expectations or the plan were changed suddenly without their knowledge. “You can have a great plan but it needs to be supported and monitored consistently. I think that too many times, some adults, teachers, or parapros, feel like [the child] performed a skill or assignment yesterday and they should be able to generalize that skill.. Many times, the skill cannot be retrieved immediately and the child is judged negatively. Staff and others may make up reasons why they shouldn't continue to support the student the way that they were previously successful.” For example, a parent may have success taking the child to the grocery store given a limited list of items, but then you decide to stay an extra 15 minutes because previously, the child was successful, but the extra time may trigger a tantrum because they’re frustrated, overwhelmed, etc. “Our children trust us, and so if we say we're going to do something, if we have a task list or a grocery list, we need to follow it.”

Griffin adds that communication plays a big role in how a child can advocate for themselves:

From management to regulation

Typical behavior therapy and IEP behavior goals can be ableist in nature and encourage us to reinforce “good” behavior with reward systems so that kids learn to be more compliant. Dr. Amy Laurent, OTR/L, psychologist, occupational therapist, and educational consultant, in her 2019 TedXTalk on compliance and kids with autism explains that there needs to be a shift around compliance, from “educational programs which focus on behavior management and focus on trying to make someone appear indistinguishable despite their unique neurology” to a system built around emotional regulation.

If the behavior is expressing an underlying problem or need, the approach shouldn’t be on the observable reaction to the problem — the behavior — but on regulating the root cause, the need, emotion, and underlying experience of the individual. This system embraces neurodiversity instead of punishing it and is a “move away from management — this external locus of control — where I am putting some arbitrary plan in place to control your behavior, to make it look like you ‘fit in’ and I’m going to shift that to regulation.” What is regulation? Dr. Laurent explains that the approach is teaching kids the tools and strategies to be able to navigate their day successfully, and regulate those strong emotional reactions, “and in that way we empower them.”

For example, parents can explore supports like speech therapy, social skills training, and structured play, and teach kids to recognize and respond to social cues, set boundaries, and communicate needs effectively. Parents can also teach kids self-advocacy skills through visual aids, Social Stories, or assistive technologies.

But if a behavior therapy silences the child’s behavior and the underlying need without giving the person a more effective way to communicate what they are trying to say or meet their needs, it is silencing that child’s ability to communicate, get their needs met, or receive the care they need. Dr. Akins explains that instead of focusing on whether or not a child is complying, which could be for many reasons, we should move into a relationship-based model where we try to understand the child’s motivations:

Common behavior challenges in children

Dealing with behavioral challenges can feel like an endless roller coaster for both parents and kids. We’ve been there — tantrums, refusing to go to school, head banging, skin picking, flopping on the floor, refusing to do tasks, biting, hitting, pushing, bullying, snatching toys, stimming, wandering off. Some of these behaviors may even become dangerous and spark safety concerns, such as when kids elope.

There is a high risk of getting lost or hurt, and if kids can’t communicate who they are or where they live, it can quickly turn into a dangerous situation. It's enough to leave anyone feeling confused, overwhelmed, and utterly exhausted. When these things happen, it’s so tough to know how to respond in the moment. And let's be real, trying to figure out the root cause and thinking about long-term prevention can seem downright impossible.

“It's one of the hardest things because in the moment, a lot of times if a child is already dysregulated, there isn't a lot that you can do,” says Dr. Scott Akins, who talks us through one of his approaches for parents using zones of regulation to help with dysregulation, especially during temper tantrums.

When dealing with these common behavioral challenges, especially ones that are more severe, such as self-injurious behavior, Dr. Burton-Hoyle and Dr. Stein recommend that parents use a multidisciplinary approach:

- Check medical history and needs. “For somebody that is physically abusing themselves,” Dr. Burton-Hoyle says, “you've got to get make sure there's not a medical sort of sort of thing going on because there are some kids that have these things that look like terrible tantrums, or meltdowns, where they're banging their head, that actually are seizures. So sometimes, when parents are very confused like, ‘I don't even know what to do,’ I certainly would video my child and make sure a doctor looks at it.”

- Look at their communication. “Do they have a way to communicate? Because sometimes if we're just focusing on a person verbally talking, that can add to the angst of their situation,” explains Dr. Burton-Hoyle. You can bring in assistive technology, pictures, stories, communication devices, etc.

- Build a multidisciplinary care team. For example, bring in a speech-language therapist, an occupational therapist, and a BCBA (and there are clinics that house all of this), not just a behavior therapist. “It's complex,” Dr. Burton-Hoyle says, “so you can't just focus on one thing because what if it's a sensory need and part of the head banging is related to a hypo reactive sort of situation with craving those different kinds of feelings? Then they're frustrated and they have no way to communicate.”

- Look at what drives behavior. Dr. Stein also emphasizes looking at what drives the behavior in a larger way, emphasizing understanding behavior, understanding relationships, and understanding the brain.

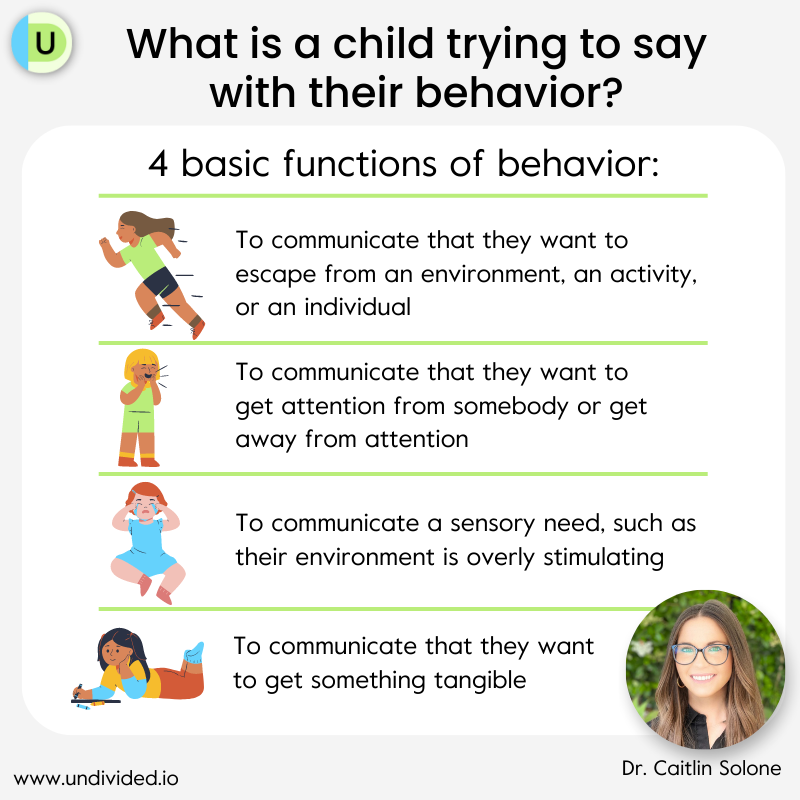

Every behavioral approach or therapy will have a different way of handling these common challenging behaviors, so we’ve gone more in-depth and shared a few of them, along with tips for supporting kids (and ourselves) through behavior challenges in our article Common Behavior Challenges in Children (and How to Approach Them).

Common behavioral interventions

Picking the right intervention or therapy for your child’s behavioral challenges can be a bit of a journey. It often involves some time, teamwork, and a bit of trial and error. For instance, ABA therapy is often suggested for kids with autism, but it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution. There are other techniques out there that might better suit your child’s unique needs and goals. So, how do you figure out which one is the best fit? And as a parent, how do you know if it’s actually working? These are the big questions we all grapple with.

A few kinds of interventions include:

- Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Intervention, or NDBI, which was developed to combat the rigidity of ABA. These interventions “share core characteristics that are less medicalized, stigmatizing, and depersonalizing, and approach skill acquisition in a more accepting, compassionate, and empathetic manner.”

- Developmental-relationship approaches that focus on the interactions between a child and their caregiver. They are based in developmental psychology and heavily rely on the relationship between parents and children to move children along their developmental pathways. These therapies are less structured than traditional ABA therapy.

- Dr. Greene’s Collaborative & Proactive Solutions (CPS) model, outlined step by step on his Lives in the Balance website, which centers on working collaboratively with a child to solve the underlying problem that is creating the external behavior. This means that challenging behaviors are a result of lagging skills, such as flexibility, adaptability, frustration, tolerance, problem solving, and emotion regulation rather than lack of motivation to be good.

- The Social Thinking Methodology, which is a social model that focuses on building a child’s social competence so that they can better navigate interactions with their peers and understand others’ perspectives while learning other crucial skills. - Neurodiversity-affirming approaches to behavior that embrace and respect a child’s neurodivergent identity and recognize that behaviors are a unique way of expressing distress and needs, and it recognizes that all behavior is communication.

Navigating all these different approaches and interventions can leave any parent feeling totally overwhelmed and confused. Which method is best for your child? Where do you even start? Then there’s the question of funding. Getting behavior supports and securing funding for them, whether that’s ABA or an alternative, can be expensive when paid out of pocket.

Remember, there are many behavioral interventions to explore, and there’s no single right answer. Finding the best approach for your child is a very personal decision. It depends on their specific needs, the goals of their therapy, and your family’s values and goals. You might choose to stick with one approach, or you might find it works better to mix and match pieces from two or three different methods. The key is to find what fits best for your child and family.

One tip Dr. Akins gives parents is to find a match that works for them and to stay engaged as much as they can. Often, parents agree to therapies or interventions that they may not fully be on board with, but it’s important that therapies and goals, whether at home or at school, be aligned with your values.

Find more in-depth information on behavioral interventions, what to think about when choosing a specific intervention or provider, and all the ways to fund them in our article Common Behavioral Interventions and Therapies (and How to Fund Them).

Behavioral supports at school

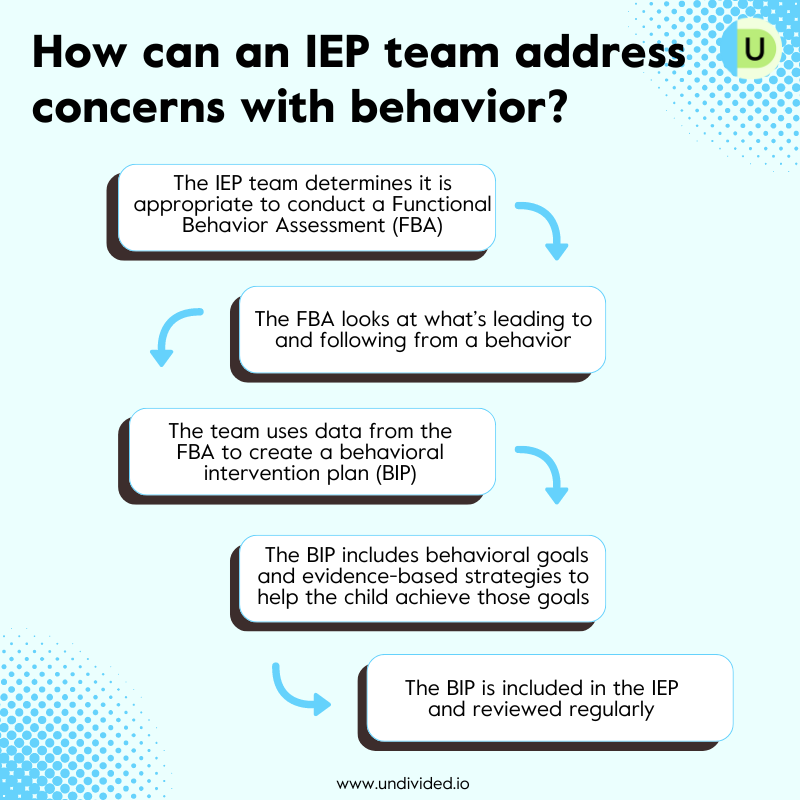

How can we get behavior supports at school that are supportive and strength-based? Dr. Pelangka explains, “Behavior supports come in many forms, such as behavior strategies (e.g. embedding visual supports, checklists, token systems self-monitoring checklists, organization systems, etc), incorporating home-school communication logs to align home and school, adding in behavior goals, adding in a behavior plan, adding in behavior intervention services (this takes the form of the school behavior team consulting and collaborating with the student’s team), completing a Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA), adding in a behavior aide with behavior supervision from the school BCBA, etc.”

Positive Behavioral Intervention Plans (PBIS), Functional Behavioral Assessments (FBA), Behavioral Intervention Plans (BIP), behavioral goals — there’s a lot to cover. Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), for example, approach focusing on rewarding good behavior and ignoring or paying little attention to “bad” behavior — as opposed to the more traditional ideas of “discipline” or punishment that uses negative reinforcement.

Dr. Caitlin Solone emphasizes the importance of PBIS and provides insights into how we can better understand our kid's behavior and how their environment plays a role in supporting them.

Some questions parents may have around behavioral supports at school include:

- What happens after an FBA?

- Are FBAs only for addressing “dangerous” behaviors?

- Should IEP goals be about reducing “bad” behaviors?

- What about non-compliance in the IEP?

- How do we write neurodiversity-affirming goals?

- Should students with “distracting” behavior be excluded from general education?

- How can parents advocate for the school to do more thorough FBAs of their children?

We answer all these questions, and more, in our article Supporting Our Children’s Behavior at School.

Supporting our kids (and their behaviors)

Behavioral challenges are tough on any parent, and it can feel like a lot to handle some days. There are many options and avenues to support you and your family. Whether it’s reaching out to other parents going through the same thing, consulting with specialists, or exploring various interventions, there’s help out there. Every child is different, so finding the right approach might take some time, but it’s okay to take it one step at a time.

Take a moment to breathe and remember: you’re not alone in this. As Dr. Stein emphasizes, “Behavior is actually a really simple thing to understand… If we can combine understanding behavior, understanding relationships, and understanding the brain, we can have a really good roadmap as to how to help kids be strong and healthy and resilient and kind. I'm not here to suggest that behavior is going to be perfect, that's not true for any human being. But it certainly helps if we can keep those really basic ideas that drive human existence in mind.”

Find a non-ABA behavior support provider

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor