Supporting Kids' Mental Health at Home and in Crisis

When a child is self-harming

Finding out your child is intentionally hurting themselves is probably one of the hardest and scariest things a parent can face. Self-harming behavior is most common during adolescence, a difficult developmental period for kids. A study from the PLOS One Journal even shows that the number of nursery and primary school pupils who self-harm is rapidly increasing, and that interventions need to extend to elementary school-aged children. Behavior can include cutting, scratching, picking at skin, and hair-pulling. While self-injury isn't the same as suicidal behavior, it's equally important for kids who self-harm to receive help.

If you suspect that your child is self-harming, some signs you can look out for include suspicious-looking scars, increased isolation, wearing long-sleeved shirts in warm weather, or avoiding getting undressed. Founder and clinical director of CARE-LA, Dr. Lauren Stutman, Psy.D., explains that with self-harm, “You want to ask if it's a superficial cut, like scratches, or if they're deep cuts. And if it's scratches, that's going to take you in one direction, and if it's deep cuts, obviously they need to be seen immediately by a psychiatrist, or even be taken to a hospital.” Usually, when a child is self-harming, it’s a coping strategy used to alleviate emotional distress they are feeling. They might not know how else to cope with how they’re feeling or have the tools to ask for help. Dr. Stutman explains more in-depth:

How to talk to your child about self-harm

When something like that happens, Stutman says, “It's best to come at it with, ‘I understand you're in horrible pain right now. And I understand that you're doing this to put yourself in less pain. And that actually makes a lot of sense. But you know, it's not a healthy way to do that. And what we want to do is to design a game plan for how we can come up with other types of interventions/safer self-soothing actions that are going to make you feel better.’” And it’s important that we approach our kids without judgment because, as Dr. Stutman tells us, kids can feel like they're failures, or that they're doing something shameful, and that can lead to more isolation and depression. She gives us more tips in this clip:

Getting help for self-harm

If you discover that your child is self-harming, it’s important to get help. Even if it’s a one-time thing, or an “experiment,” it is a maladaptive coping skill and dangerous, and it can signify deeper mental health struggles. If the self-harming is serious, call your provider or mental health specialist (and call 911 to get immediate help if the situation is life-threatening). You can also contact the crisis text line by texting HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor over text 24/7.

If the situation isn’t life-threatening, talk to your child and discuss your options. Share with them that you will be reaching out to a specialist to make that game plan. Reach out to a mental health professional about getting your child an evaluation. If you don't have a mental health professional yet, talk to your child’s provider and get a referral. Once an evaluation is completed, they will determine what treatment will be most effective. Your child may see a therapist for dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) or cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), depending on their treatment plan. Talk therapy may not work for all kids, so make sure that a variety of options are explored. Family therapy can also help.

CHOC explains, “During recovery, balance is pivotal. Try not to be invasive or to take away privileges as punishment, as this can push kids and teens away. Instead, show them your support by doing more activities together, having daily conversations, or simply allowing them to feel their emotions. No matter the outlet, your role will play a vital part and can help limit their self-harming.”

When a child is suicidal

Suicide is often linked to a mental health disorder such as depression, but ADHD, autism, and anxiety can also play a role. Suicidal thoughts can be triggered for many other reasons, such as being bullied at school, breaking up with a partner, failing a class, or experiencing abuse, loss, or other trauma. A few warning signs to watch out for include:

- Talking about wanting to die or kill themselves, or how they’re feeling hopeless, having no reason to live, or are a burden to others. This last one can be especially important for our kids if they feel that their physical or developmental disorders are a burden to their parents and siblings.

- Writing suicide notes, journal entries, drawings, texts, social media posts, or emails.

- Saying goodbye to friends, giving away prized possessions, or deleting profiles, pictures or posts on social media.

- Making dramatic changes in behavior, such as self-isolating, no longer talking to friends or family, skipping school or activities, not sleeping, sudden weight gain or loss, and/or disinterest in appearance or hygiene.

- Having a plan and access, such as showing interest in guns or weapons, medication, or hinting about a suicide plan.

- Engaging in risky behavior such as using alcohol or drugs, running away, showing rage, or hurting themselves.

Kids with disabilities are often more at-risk of having suicidal thoughts or feelings, and this can be missed by providers. They might not express their emotions the way a neurotypical child might, or the signs may be dismissed as a symptom of their disability. Children with autism, for example, are twice as likely to report suicidal thoughts when screened for suicidal ideation during routine medical assessments, according to new research from the Kennedy Krieger Institute. Children who struggle with social communication, even if they don’t have autism, are at also a high risk of suicidal behavior, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. But “many typical signs of suicidality — changes in sleep, appetite and social relationships — involve areas that are already challenging for these individuals,” so their needs might be ignored.

Getting help during a mental health crisis

If your child is exhibiting dangerous behavior and you need to intervene to stop an attempted suicide, or prevent one, call 911 or your local emergency mental health access number, or take your child to the hospital. Be sure to tell the emergency provider that your child has a developmental disability or delay.

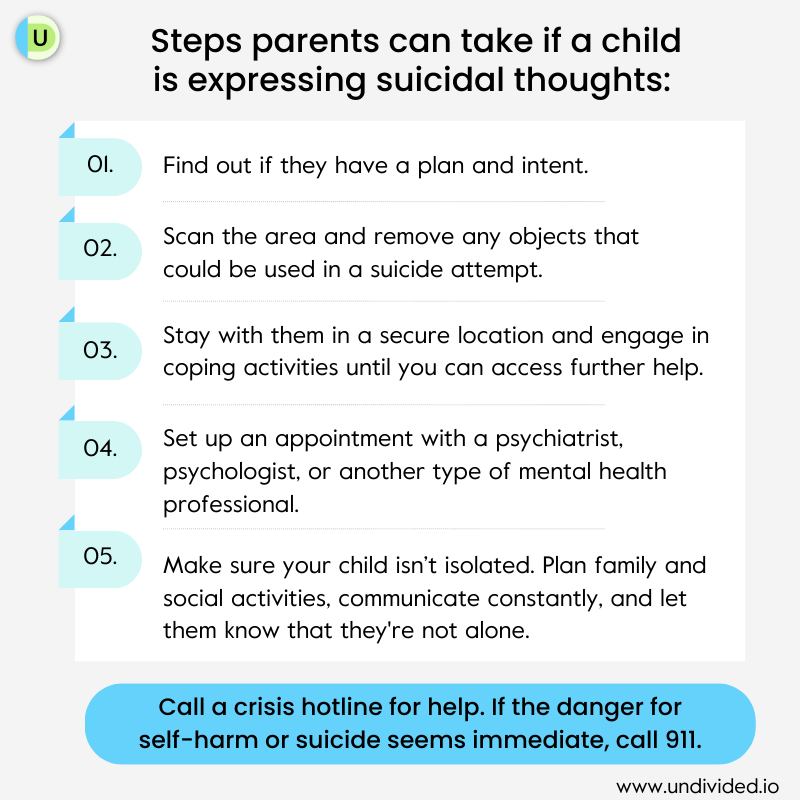

Here are the steps parents can take if a child is expressing suicidal thoughts:

Crisis hotlines for immediate support

If your child is exhibiting dangerous behavior and you need to intervene to stop an attempted suicide, or prevent one, call 911 or your local emergency mental health access number, or take your child to the hospital. Here are some options for immediate support:

National resources:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 800-854-7771, and find more resources on the DMH website. You can also use the the national suicide line by calling or texting ‘988’ or chat online on 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline’s website (website for Deaf and hard of hearing here).

- Disaster Distress Helpline: Call or text 800‑985‑5990 for 24/7 support.

- Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741 for 24/7 crisis support.

- TEEN LINE: Teens can talk to another teen by texting “TEEN” to 839863 from 6pm – 9pm, or call 800‑852‑8336 from 6pm – 10pm.

- National Suicide Prevention Deaf and Hard of Hearing Hotline: Access 24/7 video relay service by dialing 800‑273‑8255 (TTY 800‑799‑4889).

California resources:

- See this listing of California Suicide & Crisis Hotlines

- CalHOPE: Free mental health coaching and resources for teens and young adults ages 13-25, available via the Soluna app. The Brightlife Kids app is for parents of kids ages 0-12

- California Warm Peer Line: Call 855‑845‑7415 for 24/7 for non-emergency support to talk to a peer counselor with lived experience.

- California Youth Crisis Line: Youth ages 12-24 can call or text 800‑843‑5200

- If you have Medi-Cal, you can call the number on your membership card for mental health services. You can also call your local county mental health line. To find out what services are covered, call the Medi-Cal Managed Care and Mental Health Office of the Ombudsman at 888‑452‑8609. They are available Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. – 5 p.m.

- Parents, caregivers, children, and youth up to the age of 25 can receive support at the California Parent & Youth Helpline. Call or text 855‑427‑2736 to speak to caring and trained counselors. Live chatting is also available on their website.

- NAMI California has resources for family members supporting loved ones with mental health conditions. You can call their HelpLine at 800‑950‑NAMI to get information, resource referrals and support from 7 a.m. – 3 p.m.

Non-emergencies

In non-emergency situations, Dr. Stuman tells us, “If a child mentions that they don't want to live anymore, it would be good to get a psychiatric evaluation because you never know if it's serious or if they're just trying to express their feelings. But even if they're trying to express their feelings, expressing those feelings means that they should probably be working with a mental health professional.” While treatment plans can include psychotherapy, behavior management, and medication, she adds that if a psychiatrist feels that medication isn't needed, they can refer to a psychologist, social worker, or marriage and family therapist (MFT).

While suicide is rare, if a child is expressing suicidal thoughts, it’s important to talk to them so that they feel less alone. Any parent should be on high-alert if their child is exhibiting the signs listed above, but Dr. Stutman tells us that sometimes, if a child is expressing suicidal thoughts, it doesn’t always mean they are suicidal: “Kids are very black and white. So instead of saying, ‘I'm having a lot of pain right now,’ they might say, ’I hate my life, I want to die.’” She continues to say that kids don’t have the language to express everything they’re feeling and may speak in extremes.

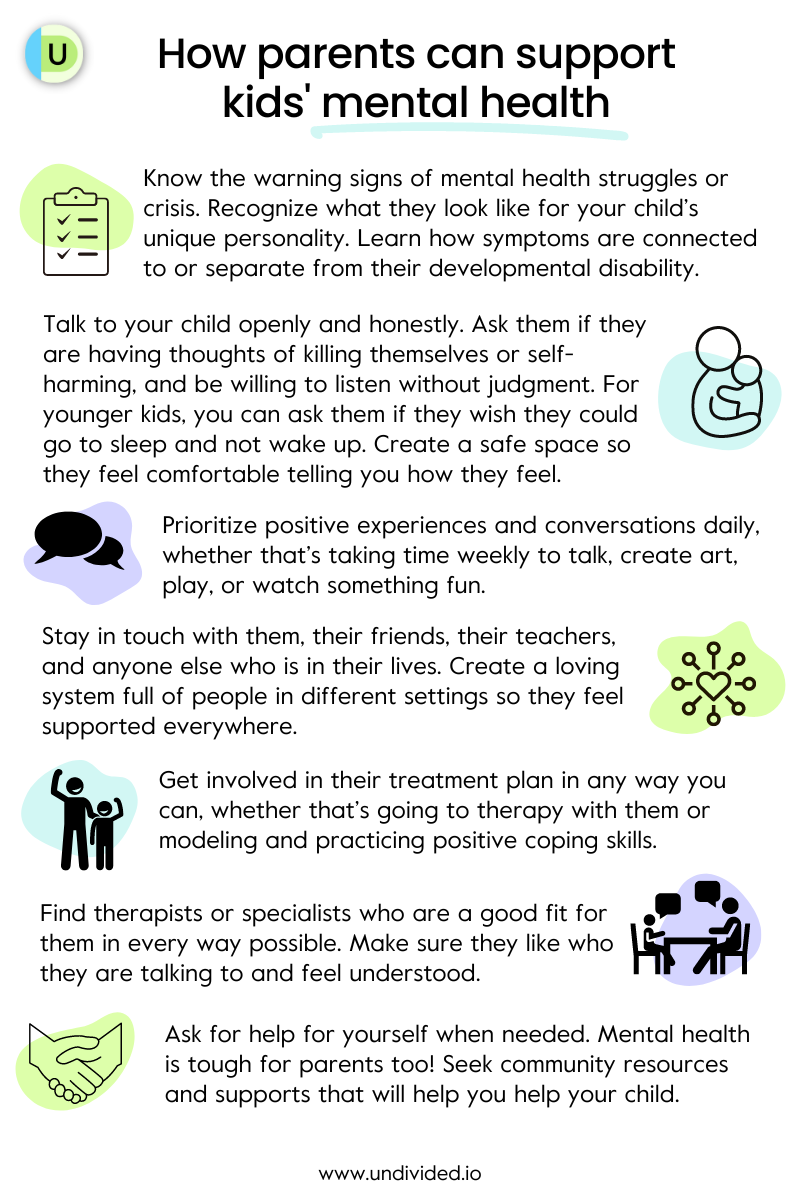

Here are some more ways you can support your child:

Supporting kids with depression, anxiety, OCD, and risky behavior

If your child is struggling and you notice the warning signs, Dr. Emily Haranin, PhD, clinical psychologist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, tells us: “Take any such behaviors seriously and seek support from a qualified provider. Practical steps include increasing supervision and limiting access to any potentially dangerous materials at home. Creating more opportunities for spending (fun) time together, playing together, doing things they enjoy, or involving them in things you are doing. This will provide additional opportunities for your child to share what’s going on in their life with you. Try your best to just listen when they share and let them know you are there for them.” Here are a few more tips to support them through mental and emotional challenges:

Supporting children with depression

- Create a safe space to talk to them openly about feelings and emotions, without judgment, and validate their feelings.

- Teach and model healthy coping strategies, such as deep breathing, positive self-talk, and journaling.

- Support healthy interpersonal relationships, such as peer group activities and spending time with friends, siblings, and cousins.

- Create healthy habits like eating and sleeping well, practicing gratitude, and moving the body through dancing, daily walks, etc.

- Make time for play! Set time during the day for uninterrupted fun — whatever makes them happy, whether that’s watching their favorite tv show, building a Lego figurine, or putting on their favorite songs and dancing it out.

- Seek professional help through school supports and private therapy.

Supporting children with anxiety

- Create a safe space to talk to them openly about their anxious feelings. Validate their emotions and model healthy responses, such as expressing, “I know you’re scared, and that’s okay. I’m here with you and I’m going to help you get through this.”

- Create safety and reliability in their day-to-day life, such as adding routines for meals, sleep, and homework.

- Teach and model calming coping strategies, such as deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and yoga or stretching.

- Create healthy habits to reconnect to the body, such as daily walks, dance class, swimming, or just going outside for 30 minutes a day.

- Seek professional help through school supports and private therapy.

Supporting children with OCD

- Create a safe space every day to speak in a supportive way and listen to your child about what they’re thinking and feeling and worrying about.

- Create “worry time,” a set time at the end of the day to save your worries for. Set a timer for five minutes and have them write or share their worries for that amount of time, which will help them regulate their ruminating thoughts.

- Seek professional help through school supports and private therapy.

- Participate in their therapy and reinforce what they’re learning in treatment at home, including supporting them as they face their fears.

- Resist accommodating or participating in their rituals, as hard as it may be. Instead, remind them of all the skills they’ve learned in treatment and encourage them to use them in the moment. Dr. Matt Biel, chief of child and adolescent psychiatry at Georgetown University Medical Center, explains: “So kids who have OCD may have been taught by therapists that when they're having an uptick in OCD symptoms, what they need to do is exactly what their OCD is telling them not to do. They need to touch that doorknob, and then touch it again, they need to not stop counting even numbers but actually go to an odd number. They need to leave their desk a mess even though it feels awful. Whatever the thing is that tends to set them off, they need to lean into that and remember that they can tolerate that distress. “

Supporting children engaging in risky behavior

- If a child is engaging in risky behavior, such as sneaking out or taking drugs, Dr. Stutman explains that parents should seek professional help and set up an appointment with a provider sooner rather than later.

- Make sure that they are always in a safe space, whether that’s at home or at a friend’s house, and that they value the parenting styles of other parents their kids are around. For example, if your child has a 9 p.m. curfew, make sure your kids aren’t sleeping over at a friend’s house who has no curfew.

- Create a safe space to speak to them about their behaviors, and how you can work together to mitigate the risks.

- Explore community or school resources that can help your child feel supported, such as school or counseling groups, mentor programs, etc.

For more tips, check out CARE-LA’s Instagram page.

Supporting our kids’ mental and emotional health every day

Have a conversation

Dr. Stutman tells us that having regular talks with our kids is a great way to start the conversation on mental health — making sure that we are listening and that they feel safe explaining things to us without judgment (and without us interjecting with advice). This may be easier when our kids are teens, but for younger or non-speaking children, we may need to tweak a few things. Dr. Stutman explains that something we can change is our language: to talk to them where they’re at developmentally in a language they can understand.

This may be a struggle, especially if your child is very young and there isn’t much information available to understand what they are feeling or experiencing. Dr. Stutman wants parents to know that it’s not their fault, and that there’s no shame in seeking help: “That's what keeps parents from sharing and that makes them isolated and more depressed and more stressed. And then they can't parent as well.”

Dr. Biel also gives us a few tips when talking to kids about things that are difficult or adverse:

Practice mindfulness, flexible thinking, and emotional regulation

Modeling mindfulness is a great way to teach our kids who to work through the stressors of life, and be present. Marriage and Family Therapist Diane Simon Smith told us, in How to Navigate Stress and Anxiety, “When we're feeling calmer, and we're feeling better, we can transmit that to our children, and we can teach them how to do it — let's take a moment, let's stop, let's breathe, let's feel our bodies with our feet on the ground and sitting in our chairs. And we're here right now; the sense of presence and being fully mindful of this moment, and stopping. Because we spend a lot of time worrying about things we did or didn't do yesterday and a lot of time thinking about plans about what's coming up in the future and worrying about it. And we miss what's really going on in the moment.”

Flexible thinking is a great coping tool to practice ourselves and model for our kids. Being flexible in our thinking means that we can change our ideas — we can think of a new solution to a problem we’re having and keep our cool when things don’t go the way we planned. It can help our kids be kind to themselves if things don’t go exactly as they expected and improve how they handle stress and disappointment.

Emotional regulation is the ability to control emotions, impulses, and inappropriate behavior. As parents, we can coach our kids through tough situations and feelings providing them with the tools to develop the appropriate emotionally regulated responses. Pediatric psychologist Dr. Rita Eichenstein also gives us some words of support we can share with our children who are struggling: “If I could look into a crystal ball and tell you it's all going to be okay. How would you live your life? How would that make things different for you? I want you to think about it because the truth is that yes, you're going to work very hard. And yes, there will be good days, and some bad days, some humiliating days, some depressing days. But there will also be joyful days and joyful moments. And somehow, you're going to get through this.”

Model positive coping strategies

One of the best ways to support our kids’ mental health and help them navigate big feelings is through modeling healthy coping skills and explaining why they are helpful. Coping skills will vary from child to child, so find what works best for you. One child may find that drawing is helpful, while another may prefer to sing or dance. Dr. Rita Eichenstein reminds parents, “You don’t have to be perfect. Cook a family recipe together. Talk about memories. Try to have shared fun experiences. Take a walk, go outside. It’s important to be physical and get moving. Put on dance music. Breathe fresh air. Try to experience nature and grounding together."

To develop positive coping strategies that will actually work, it’s important to be mindful that we meet our kids where they are and create skills that make sense for them. Dr. Stutman explains why:

Dr. Stutman gives us a few examples of positive coping skills:

OCD. “For OCD, what you'd want to do is recognize the intrusive thought, and you would say, ‘There's that thought again,’” she explains. “So you separate yourself from the thought. And then you might develop a hierarchy for exposure, where you would delay the compulsion; then you would change it up and do the compulsion to reverse order; and then eventually, you would delay it further until you stop doing the compulsion on purpose, or you replace it or redirect to something else.” She gives a good analogy you might share with your child: “It’s like we're in the dark and we have a flashlight, and where do you want to shine your flashlight?” So you could shine the flashlight on the original thought or you say, “Oh there’s that thought again,” and shine the flashlight somewhere else, to another thought or behavior, or write in your journal.

Anxiety and depression. “A major coping strategy is behavioral activation,” she explains. “That's really where you do the opposite of what you want. So if you want to sit on your bed, you do the opposite — you take a shower, you make plans, and you go out. So we don't want to accommodate for anxiety, OCD, or depression too much to where we let them take charge and dictate what we do. Sometimes, we want to do the opposite of what feels right. So teaching kids about that and how that kick starts certain neurotransmitters — dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin. All those things are going to fight against the depression. Movement is also good for all of those things. I think that a lot of times, doctors, especially psychologists, don't really touch on things other than the psychological, and movement is really psychological. It's really important that our kids are getting exercise, especially if they're suffering with a mental illness.” She adds that changing the setting, like going for a walk outside, is also great for addiction, depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions.

Dr. Biel adds that, “Kids have a lot of skills and you can remind them that they've been through tough times before. They may have had anxiety or OCD for the first time when something tough was going on academically, or when there was a loss in the family, or when they were struggling socially, and remind them of those previous successes that they had — ‘You figured out how to do that before. How'd you do that? Do you think any of those things you did back then might be useful now?’”

Teach self-advocacy

A big part of struggling with mental health is that sometimes, kids can feel alone, misunderstood, or different, especially if no one is talking to them about emotional health or validating their feelings. Our kids can feel extra vulnerable if they have a harder time making friends or feeling left out of friend groups; feeling like they’re not as smart as other kids, especially if they have a learning disability; or feeling singled out if the way they communicate is being misinterpreted. While these are all things that can break a parent’s heart, there is a lot we can do at home to help them step out into the world more able to cope with the challenges. We can teach them about their disability and personal history, encourage them to express their needs, and empower them to make their own choices.

It’s hard enough to ask for help when you’re an adult, and it’s that much harder when you’re a kid. Helping our kids learn how to ask for help can be an important step in teaching them self-advocacy skills, alongside teaching them about personal safety and boundaries. Of course, the way you speak to them will depend on your child’s age and skills. Younger children may not be able to express what’s actually bothering them, and teenagers may often hide situations from you that are embarrassing if they worry you’ll get angry at them, so it’s important to create safe spaces for them to talk to you, and to give them the option of talking to a therapist. And a great way to teach them how to ask for help is to model it yourself!

Key takeaways for parents

Dr. Stutman leaves us with a few words of advice as we navigate support our kids’ emotional and mental well-being:

Model that it is normal and healthy to prioritize mental health. Practicing good mental health hygiene shouldn’t be something to be ashamed of. As parents, we can show our kids that mental health is an important aspect of being a healthy, whole individual — just as important as physical health — and having open, honest conversations is a good start to creating those safe spaces for our kids.

Don't settle for somebody that feels wrong. It’s important to build a team of specialists who are going to be champions for your child! Make sure that you and your child feel comfortable with their psychologist, therapist, social worker, school therapist or counselor, and/or psychiatrist. And listen to your gut! If you feel that a certain specialist isn’t quite right for your child, ask your child’s primary care provider, health plan, or friends and family for referrals to other people who may be a better fit.

Learn about your child's disorder or diagnosis. When you feel ready to dive deeper into your child’s mental health condition, whether they are diagnosed or not, learn about it in any way that feels okay for you — whether that’s through online searches, asking specialists or other community resources, or talking to other parents. With information on hand, you can more easily learn how to validate your child, sit in their experiences with them, and see them without judgment. This way, you can model to your child that you see and accept them fully as they are.

Pay attention to your own stress levels and your own mental health issues. It can be terrifying and overwhelming to watch our kids experience emotional hardship. It requires a lot of emotional bandwidth on our end, so it’s important that we monitor how we’re doing and feeling, too. You can find more tips on how to maintain mental wellness and regulate stress in our article The Most Underrated To-Do? You. Once you read that, you can identify the areas where you aren’t getting your needs met and create a self-care plan.

Practice ourselves what we want our children to do. When it comes to mental health, the phrase “do as I say, not as I do” doesn’t quite work. If we want our kids to learn and practice positive coping skills when it comes to their emotions, we need to model what that looks like. Some things we ourselves can practice include flexible thinking, emotional regulation, and asking for help.

Find community and other support and resources. Dr. Stutman tells us that parenting groups are really healing, and you get to hear that other people are going through this with you. You can also create more opportunities for your child to connect with other kids, whether that’s through social-rec activities, play dates, or peer support groups. Positive, interpersonal relationships are a great protective factor for mental health.

Marriage and Family Therapist Diane Simon Smith told us, in How to Navigate Stress and Anxiety, “I wish I could have a firm answer to everybody's questions about how to make this all better. What I wanted to say is to hold ourselves gently, with kindness and compassion, to remember to breathe, to remember to take care of our basic needs for ourselves and our children. And we put our heads down at the end of the day, if everybody is healthy, and okay, and in one piece, we've made it through another day.”

More resources for parents

Online:

- CDC Children’s Mental Disorders

- CDE Resources for Students in Crisis

- CDE Youth Suicide Prevention Resources

- CHOC Mental Health Resources

- CHOC Mental Health Parent Tips

- Medi-Cal Specialty Mental Health Services

- Crisis hotlines and resources

- National Institute of Mental Health

- Find the LA County Department of Mental Health services, programs and facilities serving your area.

Books:

There are tons of resources out there that can help you open up dialogue and connect with your child: books, tv shows, movies, TED talks, etc. A few books that might help your child understand their feelings include:

For depression (and emotional health)

- Maybe Tomorrow (children)

- When Sadness is at Your Door (children)

- The Color Monster: a story about emotions (children)

- The Monster Parade (children)

- Me and My Fear (children)

- A Blue Kind of Day (children)

- Tough Guys (Have Feelings Too) (children)

- A Terrible Thing Happened (children)

- Red Tree (children)

For OCD and anxiety

- Ruby Finds a Worry (children)

- What to Do When You Worry Too Much (children)

- A Thought Is Just A Thought: A Story of Living with OCD (children))

- Up and Down the Worry Hill: A Children’s Book About Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Its Treatment (children)

- Kissing Doorknobs (teens)

- Not As Crazy As I Seem (teens)

- Brave: A Teen Girl's Guide to Beating Worry and Anxiety (teens)

Other recommended reading

- Some Bunny To Talk To: A Story About Going to Therapy (children)

- When a Donut Goes to Therapy (children)

- CHOC Anxiety Recommended Reading

- CHOC Eating Disorders Recommended Reading

- CHOC Suicide Prevention Recommended Reading

- CHOC Depression Recommended Reading

Find more mental health resources in our articles Mental Health for Kids with Disabilities 101 and Mental Health Treatment Options for Children and Teens with Disabilities.

Support my child’s mental and emotional health

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor