Dyscalculia 101

Dyscalculia is a learning disability that impacts a person’s ability to understand math and other number-based information. Somewhere between 3 and 7% of people live with dyscalculia, making it somewhat less common — or, more accurately, more frequently misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed — than learning disabilities like dyslexia and dysgraphia. If left untreated, dyscalculia can cause people to experience mental health issues such as depression and anxiety when dealing with numbers and math.

To talk through the details of diagnosis, the different intervention approaches, and how to approach dyscalculia if your child has other co-occurring diagnoses, we reached out to Dr. Anneke Schreuder from Dyscalculia Services.

Early signs, symptoms, and causes of dyscalculia

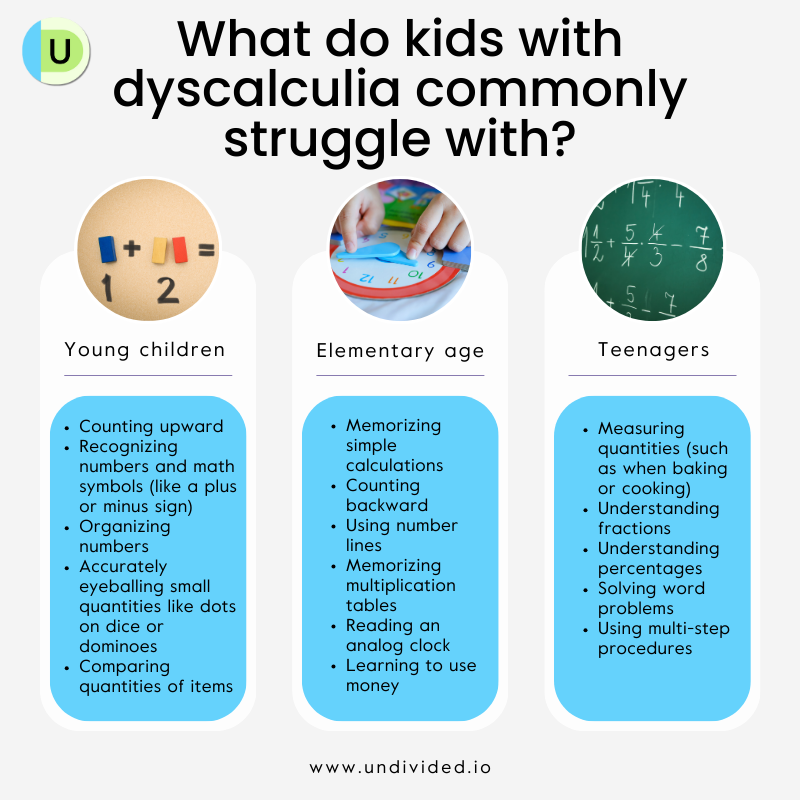

Dyscalculia can occur as a result of neurodevelopmental differences or after experiencing a traumatic brain injury, according to the Cleveland Clinic. Symptoms of developmental dyscalculia can present differently depending on a person’s age but usually begin to emerge in childhood as soon as children start learning about numbers.

Experts don’t know what exactly causes dyscalculia and other developmental learning disabilities, Schreuder says, but the conditions appear to run in families. Like other learning disabilities, dyscalculia symptoms exist on a spectrum and can be mild, moderate, or severe. It’s important to note that dyscalculia does not occur as a result of laziness or a child “not trying hard enough” — it occurs because of physical differences in their brain.

“You can see a different pattern of brain activation for people with and without dyscalculia. So this is not something they fake,” Schreuder says. “It’s really the brain structure and also the function of the brain.”

Dyscalculia, like other learning disabilities, is considered a Specific Learning Disorder (SLD) in the DSM-5 and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), meaning it isn’t differentiated from other learning disabilities despite its unique symptoms. You can read more about different SLDs in our article Specific Learning Disabilities 101.

According to the DSM-5, a person must experience the following symptoms persistently for at least six months in order to qualify for an SLD diagnosis:

- Persistent difficulties in reading, writing, arithmetic, or mathematical reasoning skills, including slow and laborious reading, poor written expression, problems remembering numbers, or trouble with mathematical reasoning

- Academic skills in reading, writing, and math well below average

- Learning difficulties that begin early, during the school-age years

- Difficulties that “significantly interfere with academic achievement, occupational performance, or activities of daily living” and cannot be “better explained by developmental, neurological, sensory (vision or hearing), or motor disorders”

Do any disorders commonly co-occur with dyscalculia?

Dyscalculia often co-occurs with other learning disabilities (like dyslexia and dysgraphia), ADHD, autism, and sensory processing disorder. ADHD is particularly common; one study found that up to 45% of children with ADHD have a learning disability or combination of learning disabilities, and another found that up to 11% have co-occurring dyscalculia specifically.

People with dyscalculia are also at a higher risk of having mental health conditions including anxiety disorders, behavior disorders, bipolar disorder, and depression. Negative school experiences and repeated struggles with math can directly cause the development of mental health symptoms and conditions because of fear of failure and diminished self-esteem, according to a 2019 study.

Math anxiety, while not an official diagnosis, is a common experience in people with dyscalculia that can significantly inhibit their ability to learn, Schreuder says. “You can see in an MRI if people get really nervous [while doing math] that the blood flow is redirected away from the centers of the brain where you do math. And for some students, they can recuperate in 5 or 10 minutes. But for some students, this whole redirection of blood flow can take three-quarters of an hour, 50 minutes to normalize. Well, by that time, your math class is over, and you didn’t pick anything up.”

Signs of math-related psychiatric issues to look out for include:

- Math-induced anxiety and/or panic

- Math-induced agitation, anger, or depression

- Fear surrounding math and going to school in general

- Physical manifestations of anxiety and depression including nausea, increased heart rate, sweaty palms, vomiting, sweating, and stomachache

It’s important to note that not all struggles with math and numbers are caused by dyscalculia, Schreuder says. Inattention issues caused by ADHD, for example, could cause someone to struggle to remember multiplication tables or to lose track of their progress when working out a math problem. This is why IEP assessments are critical — they help ensure your child receives the proper interventions, remediations, and accommodations based on their specific condition(s).

The dyscalculia diagnosis process

Children can be screened easily for learning disabilities, including difficulties with math and numbers, as early as preschool. Many free screening tests exist that take only three to five minutes to administer; those who score below what is expected can get a more in-depth assessment that can give the diagnosis of a specific learning disability in math or dyscalculia.

As with other learning disabilities, early intervention for dyscalculia is key to take advantage of the brain’s plasticity. Early intervention can also help prevent the development of math-related mental health issues, especially anxiety and depression, Schreuder says.

“There are still adults who, when they think back about being in a classroom, get emotional and say, ‘Oh, it was horrible. I really dreaded going into the door of that math room.’”

Unsurprisingly, learning differences like dyscalculia are usually recognized by teachers or parents after a child starts elementary school and inevitably struggles with math and numbers. Some states require public schools to proactively screen all students for potential learning disabilities, but most deal with it on a student-by-student basis because of limited resources.

Who can diagnose dyscalculia?

According to the California Association of School Psychologists (CASP), any licensed educational psychologist (including those working in school districts) can make a diagnosis “if they have the training and knowledge in that area.” This may differ depending on the state where you live.

A dyscalculia diagnosis typically comes by way of an IEP assessment, where a team of special education teachers, occupational therapists, speech therapists, physical therapists, and educational psychologists work together to identify and diagnose any and all potential disabilities. You can learn more about the assessment process and how to request one for your child in our IEP Assessments decoder.

What assessments are used for dyscalculia?

To test for dyscalculia, evaluators look at a child’s number sense, computation skills, math fluency, mental computation, and quantitative reasoning using assessments such as the Woodcock-Johnson IV Calculation subtest or the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children Arithmetic subtest. This can be combined with the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Wide Range Achievement Test, or KeyMath 3 DA. Your child should be evaluated for other learning differences as well because dyscalculia often co-occurs with dyslexia and other learning disabilities.

School-based IEP assessments, while comprehensive, are designed to find out whether a student meets the criteria for a disability that would impact learning. Depending on the qualifications of the assessor, a school-based assessment may not be thorough enough to diagnose dyscalculia.

What if you disagree with the school's assessment?

Parents who feel their child was not assessed accurately or thoroughly have the right to request additional assessments, including an Independent Educational Evaluation (IEE), at public expense. An IEE is typically done by a clinical psychologist or a neuropsychologist who is not associated with the school district. This can be especially important if a child has more than one diagnosis.

If your child’s school district doesn’t agree to provide an IEE, an alternative option is to check with private health insurance to learn whether a psychoeducational assessment can be covered medically.

Interventions and remediations for dyscalculia

While dyscalculia cannot be treated with medication, different therapies and teaching methods can help your child develop effective compensatory strategies for their math struggles. The interventions and remediations best suited for your child depend on their unique dyscalculia-related issues. “Basically, you want to see what is the issue the student has and go back all the way to that level,” Schreuder says. “There is no one best program — you always need to look at the student individually.… And that leads to your 504 plan or your IEP.”

Potential interventions could include:

- Use of Cuisenaire rods, number tracks, and number cards

- Behavioral interventions (if a student also has behavioral conditions)

- Multisensory instruction (like asking a student to solve a problem using a digital dance mat)

- Educational therapy

In addition to the multisensorial in-person instruction, Schreuder is a big fan of computerized intervention programs that gamify the learning process, such as Meister Cody and Dynamo Maths, to mention a few. “It’s much nicer for students to play addition and subtraction games [with immediate feedback] than having to do boring worksheets,” she says.

Specialists included on a child's care team for dyscalculia may include a neuropsychologist, educational psychologist, or educational specialist working together with the child's special education teacher. An educational therapist or tutor may also help.

Any interventions and remediations should be explicitly outlined in your child’s IEP and have goals directly attached to them for progress-tracking purposes. Learn more about progress-tracking in our article Progress Reporting for IEPs.

IEP and 504 accommodations for dyscalculia

Of the 13 eligibility categories that qualify a child for an IEP, dyscalculia falls into the classification of Specific Learning Disability (SLD). But because IDEA is very specific with what qualifies as a disability, sometimes children are denied services unless the dyscalculia is shown to be severe enough to cause major impairment and adversely impact educational performance. However, children who are unable to qualify for an IEP may still be able to receive services and supports under a 504 plan.

The following are some common dyscalculia accommodations that can be included in a child’s IEP or 504 plan to help them succeed in school, according to Schreuder:

- To reduce anxiety, don’t call on the student to answer math questions in class unexpectedly.

- Allow the student to take pictures of note materials so they don’t have to copy them down.

- Give the student extra time to complete in-class and homework assignments.

- Allow the student to take math tests in a quiet room.

- Provide the student with lesson outlines and previews before class starts.

- Provide assistive technologies like calculators, graph paper, graphing tools, math notation tools, and graphic organizers for math.

- Allow the student to write answers directly on the test paper instead of having to fill out a scantron.

You can find additional suggestions in our article List of Accommodations for IEPs and 504s.

Supporting your child with dyscalculia at home

It’s critical for parents of children with dyscalculia to paint math and numbers in a positive light, Schreuder says — especially when they themselves struggle with math concepts or even dyscalculia.

“We know that this runs in families … so the parents might have a not-so-good memory of their own math class, but it is not a good plan to share that with their kids and start talking negatively about math,” Schreuder says.

Instead, Schreuder suggests making time to explore math concepts with your child in a fun and friendly way. Play dominoes and ask your child to count the dots on each domino as you go. (You can also do this with dice.) Board games involving math can also help your child develop their numeracy skills.

Most importantly, Schreuder says, when your child keeps struggling to solve a homework question, don’t answer it for them. Instead, work through it with them to better understand where in the problem-solving process they’re getting lost. And don’t forget to encourage them when they do figure it out!

It’s also critical to teach your student how to advocate for their educational needs and accommodations, Schreuder says, especially as they enter middle and high school. “You want them to stand on their own legs and become their own advocate and feel comfortable to say, ‘Yes, I have dyscalculia, and this is why I need this extra time.’”

How laws could better support children with dyscalculia

Because most states don’t require schools to proactively screen students for potential learning disabilities, many students — especially those with less obvious support needs — fall through the cracks of the educational system without receiving the interventions, remediations, and accommodations they need to succeed, according to Schreuder.

The key to combating this is twofold, Schreuder says. “Just doing screening is not enough. We need to make sure that teachers have a better understanding of what dyscalculia is, and also that schools will have resources [to remediate it].”

Support my child with dyscalculia

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor