Intellectual Disability 101

At Undivided, there are words that we never want to use. In this article, we do discuss an outdated term for intellectual disability that parents might find in older documents or, unfortunately, in materials still being used. We feel that it’s important to use the term here in the context of its history and begin with a content warning.

Rosa Marcellino, a nine-year old-girl with Down syndrome, was upset that her Maryland school labeled her “mentally retarded” in her IEP. She and her siblings were not allowed to use the R-word or any other slur. The family worked hard to draw attention to the issue through their Maryland senator and the state government. In 2010, President Obama signed Rosa’s Law, which outlawed the use of the term in any federal documents (including IEPs) and replaced it with the term “intellectual disability.”

During the signing ceremony at the White House, President Obama quoted Rosa's brother Nick, saying, “What you call people is how you treat them. If we change the words, maybe it will be the start of a new attitude toward people with disabilities.” Sadly, while we changed the words, there is still a stigma today attached to intellectual disability, perhaps more than any other disability. Despite the ableism around it, a label of intellectual disability does have some benefits (more on this later). And as parents, there are many ways we can help our children feel a sense of belonging and support at home, at school, and the world at large. In this article, we explore how intellectual disability is identified and offer resources for parents looking to support their child with an intellectual disability.

What is intellectual disability and how is it diagnosed?

Rosa’s Law changed the term we use to refer to intellectual disability, but the definition under Section 300.8 of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) remains the same: “significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning, existing concurrently with deficits in adaptive behavior and manifested during the developmental period, that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.” Clinically, the diagnostic criteria of intellectual disability in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), is very similar to IDEA: “a substantially below-average score on tests of mental ability or intelligence, and limitations in the ability to function in areas of daily life.”

Dr. Ann Simun, a clinical neuropsychologist and former school psychologist, explains how intellectual disability is identified, with the first step being looking at the child’s early development.

In simpler terms, intellectual disability (ID) is diagnosed when a person has significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior.

Intellectual functioning or intelligence refers to general cognitive capacity, such as learning, reasoning, and problem-solving. This is usually measured by an IQ test, where a below-average score can indicate a significant limitation in intellectual functioning. In general, scores of between 80 and 120 on an IQ test are considered average in the United States. Scores of 70 or 75 are sometimes given as the cutoff for determining possible intellectual disability.

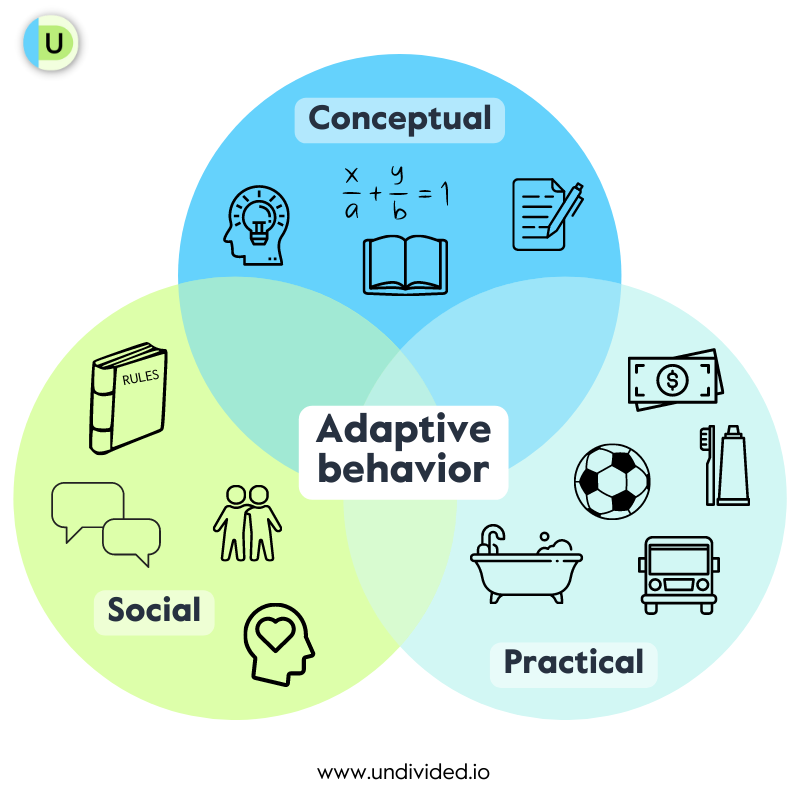

Adaptive behavior refers to self-care skills across several domains, including conceptual, social, and practical skills that are learned and performed by people in their everyday lives:

- The conceptual domain includes skills such as language, reading, writing, math, reasoning, knowledge, memory, and self-direction.

- The social domain includes empathy, social judgment (including gullibility/naïveté), interpersonal communication skills, the ability to make and retain friendships, social skills, social problem-solving, and rule following.

- The practical domain includes being able to be functionally independent when it comes to personal and self-care (e.g., hygiene, toileting, dressing), daily life skills (e.g., job responsibilities, household tasks, money management, recreation, school and work tasks, phone usage, healthcare), and mobility (e.g., occupational skills, travel/transportation usage, safety).

Dr. Simun explains that the second part of identifying ID is assessing intellectual functioning. Hear in this clip how psychologists use IQ tests to identify intellectual disability in children by looking at scores in standardized tests of cognitive ability:

What causes intellectual disability?

Intellectual disability affects more than two million individuals in the U.S. alone — approximately 1–3% of the population. Males are more likely than females to be diagnosed with intellectual disability. ID is commonly associated with conditions such as Down syndrome, Fragile X, autism, and cerebral palsy; however, that does not mean every child diagnosed with these conditions will necessarily have an intellectual disability. For example, 30-50% of individuals with autism also have ID.

According to the National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities, the causes of intellectual disabilities vary from genetic conditions (such as Down syndrome and Fragile X) to pregnancy issues, complications at birth, health problems early in life (including diseases such as measles), and contact with poisonous substances, such as lead and mercury. But for many children, the cause of their intellectual disability is unknown.

Levels of intellectual disability

Just as every individual is unique, so is every case of intellectual disability. No two people are affected exactly the same by ID. To try to quantify the impact that ID has on a person in order to secure the appropriate services and supports for them, it is important for parents receiving a diagnosis of intellectual disability to understand how standardized IQ scores work. Often, a bell or normal curve is used to explain the level of intellectual disability a person has, which covers a large range of cognitive ability: mild, moderate, severe, or profound.

Approximately 85% of individuals with ID fall into the range of mild intellectual disability. If an IQ test is used to assess, mild ID scores range from 50 to 69, moderate from 35 to 49, severe from 20 to 34, and profound from 0 to 20. The approximate breakdown of people with ID falling into each category is as follows:

- Mild ID (IQ 50–69): About 85% of persons with ID

- Moderate ID (IQ 35–49): About 10% of persons with ID

- Severe ID (IQ 20–34): About 3.5% of persons with ID

- Profound ID (IQ 19 or below): About 1.5% of persons with ID

Dr. Simun tells us that depending on where they fall in the range of intellectual disability, “those children are going to have different programs, different recommendations, different needs, different levels of functioning. So it does matter — mild, moderate, severe, profound — and some school psychologists will take the easy road and not break it down.”

A note about profound ID

Dr. Doreen Samelson, licensed clinical psychologist and chief clinical officer at the Catalight Foundation, explains that children with profound ID are often diagnosed at or shortly after birth, and they differ from children with mild, moderate, or severe ID:

Dr. Samelson explains that people with profound ID often also have complex medical needs that contribute to and complicate their cognition and their ability to take care of their own needs: “Almost all of those folks who have cognitive ability in the severe and profound range have a co-occurring disability. We often see a group of disabilities, often connected to a devastating genetic disorder or severe birth trauma. But you rarely get somebody who doesn't have other disabilities. So you may have someone who is also blind, has cerebral palsy, or other medical problems. There's just a whole bunch of different issues that can co-occur with profound ID.” She adds that people with mild to moderate intellectual disability can be pretty healthy or have less medical or physical conditions, but complex medical needs almost always exist when you get into the population of people who have profound intellectual and multiple disabilities, or PIMD.

Figuring out how kids with profound ID communicate is very important in understanding how they feel. Communication is often the key to behavioral health. Samelson's program aims at increasing communication and engagement. Samelson explains that parents often intuitively know what their child is trying to communicate, through an understanding of body language, vocalizations, and other non-verbal forms of communication.

Samelson says the important thing in treating children with profound ID is to address the needs of the whole family, including parents and siblings. Individuals with profound ID often need round-the-clock care, which has a heavy impact on the whole family. Here are some tips she gives parents to navigate the journey from birth to adulthood:

Eligibility for school services and public benefits

Intellectual disability qualifies as one of the 13 categories under which a student may be eligible for special education and an IEP. Many states also have a category of “Developmental Disability” for students under the age of nine.

Dr. Simun tells us that she knows why parents are afraid of the intellectual disability label:

When labels can help

Despite the stigma attached, a label of intellectual disability has some benefits, especially in adult life. Dr. Simun says, “Sometimes, we are not going to shy away from an intellectual disability diagnosis. If your child actually has intellectual disability, you need to know that it does garner you some benefits, particularly after they leave school. So when they're out of the K–12 system and they have an ID finding that's current on their record, that may entitle you to certain kinds of health benefits and supports in the community.”

Intellectual disability is considered a developmental disability, so state disability agencies may provide support. For example, in California, individuals with ID are generally eligible for Regional Center services at any age. In other states, they may be eligible under the Department of Developmental Services. Children under age three will qualify for early intervention services, such as Early Start in California. Where the disability impacts two or more aspects of daily living, children in California older than age three may also be eligible for Medi-Cal and possibly for IHSS.

Assessing intellectual disability for an IEP

Typically, the process of assessing a child for an IEP under ID will include an assessment of their IQ and an assessment of their adaptive skills. Parents need to be familiar with how standardized tests work, in terms of placing their child’s performance on the test on a bell curve to establish if they have “significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning.” Dr. Sarah Pelangka, special education advocate and owner of KnowIEPs, tells us, “Most standardized tests aren't a valid representation of IQ for students with DS. I also often see psychs administer verbal cognitive tests when there is an underlying communication impairment. It is important for families to know 1) there are nonverbal measures, so always ensure the nonverbal scores are being included and considered and, 2) know which standardized measures are more valid considering their child's diagnosis.”

You’ll want to pay attention to several factors during the assessment process:

- Does the description “subaverage” refer to a result at least two standard deviations below the mean? In the case of an IQ test, the mean, or average, score is 100, and one standard deviation is 15, so subaverage would refer to a score of at most 70.

- Is it possible that other disabling conditions have interfered with the IQ test, such as challenges in language, vision, motor, speech, and communication?

- Was the child assessed in all the languages spoken in the home, including ASL?

- Did the child’s behaviors interfere with their performance so much that the test is not valid?

- Is the child’s placement on the curve (mild, moderate, severe, or profound) being properly reported?

- Is the ID label being applied using only a single measure or test?

- Was each test conducted in a way that was valid and reliable?

- Is the testing being used solely for eligibility and labeling or can it identify strengths that can be leveraged in the child’s education?

If you find that your child was not appropriately assessed for any of the reasons above, or you are in disagreement with the district’s assessment for any reason (so long as it is within the two-year statute of limitations), you have the right to request an independent educational evaluation (IEE), which is a comprehensive assessment conducted by a qualified clinician who is not associated with the school district.

Can parents refuse IQ testing?

As a parent, you will be asked to sign a consent for your child’s initial IEP assessment and subsequent triennial assessments. This is a good time to have a conversation with the school psychologist and express your concerns about how your child will perform on an IQ test, given their communication and behavioral challenges. You may want to put these concerns in writing. Some parents prefer that their children not be subjected to IQ tests, for a variety of reasons.

Parents might be concerned that their child’s communication and behavioral skills are likely to impede any real assessment of their cognitive abilities. For some parents, the idea of a single type of intelligence is scientifically flawed. The school has a responsibility to assess in all areas of suspected disability. If your child has a syndrome or condition associated with ID, that is certainly an area of suspected disability. Although you are asked to consent and can refuse, most attorneys recommend that rather than refusing to consent, you allow the district to assess and then request an IEE if you disagree with the results.

Special education attorney Bryan Winn tells us, “I always advise my clients to consent to the district's assessments requests in their entirety. If the parent disagrees with the assessment in any form, the district can challenge the refusal of the parent via lawsuit. As a result, the district will get the assessment done even if the parents challenge it because it is the district's right to do the assessments. If the parent believes that the assessment results are incorrect, they can always ask for an IEE to challenge the results of the assessments. The district has the right to assess, and the parents have the right to challenge the assessments.”

This does not adequately address the dilemma parents face, but it does indicate that attorneys do not consider refusing to consent to testing a winnable strategy. Instead of refusing IQ testing, parents can also request assessments or processing measures that include school or work samples, observations, and nonspeaking or autism-specific standardized scoring.

A note on IQ tests and racism

IQ tests have been historically racist. In California, schools are not allowed to use IQ tests or standardized cognitive assessments to develop an IEP for an African-American or Black child. The ruling comes from a lawsuit in 1971 known as Larry P v. Riles in which the District Court of Northern California determined that the IQ tests used were biased toward labeling African-American children with ID. Dr. Pelangka tells us, “Although the original intent was to not over-identify African-American students in SDC classes, the case law has almost had the opposite effect after all these years. Now, psychologists will just not administer any tests in the area of cognition. Many students often go undetected and, as a result, lose out on services. Many processing measures can be administered when considering African-American students for ID.“

What accommodations and supports might a child with an intellectual disability need?

Students with ID may need support in communication, speech and language development, and fine motor and gross motor development. They likely need help with academics; while some may require a modified curriculum, most will not and can be supported by way of accommodations. Modification of curriculum and teaching strategies will vary from person to person. Although some students with ID will need specialized and explicit instruction in functional skills toward independence, that is only 1% of the special education population.

Modified curricula

While students with mild ID may not need any modifications in curriculum, those with moderate or profound ID are likely to need curriculum modifications so that they can learn at their own pace. This is not a reason to exclude them from a general education placement, but it can have a significant impact on their ability to earn a high school diploma.

Dr. Pelangka tells us, “The assumption is often that students with ID require a ‘functional skills curriculum’ and this is just not true. I always encourage families to push for an inclusion specialist and fight for their child’s rights to be included. Most teachers simply don’t know how to accommodate and modify curriculum; they just prompt and redirect and do it for the student, or they give the student busy work. Parents should fight for a true inclusion specialist and fight for training so that teachers know how to properly support their child. It is not an aide’s job to modify on the spot — it is a teacher's job.” She adds that it’s important that consult-collab minutes be written into the student’s IEP to allow for that time to modify, but finding that time can be hard, and that’s a systemic issue that the school admin needs to address.

Parents need to be aware of the difference between accommodations and modifications and on the impact of modifications on earning a diploma. Students with significant cognitive disabilities can qualify for alternate assessment, such as the California Alternate Assessment that opens an alternate pathway to a California diploma.

Accommodations and supports

We’ve compiled the following list of accommodations and supports that students with ID may need. Please note that this list is not exhaustive but is a starting point to use when discussing accommodations and supports with your IEP team. Each child has unique needs that should be addressed within their own highly specific IEP.

- Chunking materials

- Using visuals/illustrations to stimulate memory, guide behavior, or provide a checklist of instructions

- Access to technology (low tech and high tech — for ideas, see Assistive Technology Tools to Empower Students with Disabilities)

- Connections to real life pictures/experiences

- Condensed and concise academic content

- Pairing words/phrases with body or hand movement (gestures)

- Embedding supports into learning

- Hands-on math to teach concrete concepts before abstract concepts

- TouchMath and Numicon, complete with visual learning strategies to help kids with numbers and math

- Modeling and using Social Stories

- Behavioral therapy, such as ABA or other alternatives

- Support for functional skills, such as toileting, getting ready for the day, using money, and self-advocacy

- Steps to Independence is a great program that offers step-by-step instruction to teaching life skills for the home.

- Specialized instruction in reading, starting from a whole word approach, and introducing decoding through chunked phonemes (example: teach word families instead of breaking into individual sounds), and a structured literacy approach that gives explicit instruction in phonics

- Depending on the child, therapists have seen improvement with teaching both sight words and decoding, with more and more research stating that decoding is possible.

- Edmark, a reading and writing program developed for visual learners with cognitive disabilities

- Programs like Clicker that allow for written expression

- Total communication approach as a way to help children with ID communicate, including the use of sign language and Augmentative Alternative Communication (AAC)

Common therapies and specialists

As with accommodations, any school services such as occupational or speech therapy should be discussed by your IEP team because every child has unique needs. You can see our article about IEP related services for examples of what therapeutic services the school may be able to provide and how they might benefit your child.

Key takeaways for parents

Learn about intellectual disability. If your child has been diagnosed with an intellectual disability, when you feel ready, learn as much as you can about ID. Some great organizations you can explore are the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and The Arc of the United States.

Encourage independence in your child. Help your child learn daily self-care skills and personal safety. Read our articles Teaching Functional Life Skills, How to Teach Boundaries and Puberty, and Toilet-Training Tips and Strategies for more information.

For kids with profound ID: Learn how they communicate and foster a sense of engagement. “We underestimate what's going on because they can't talk,” Dr. Samelson tells us, “but just because somebody has a very low IQ doesn't mean that they're not thinking. It doesn't mean they don't have wants and desires and opinions about things…These folks are pretty complicated and they have a lot of needs, so you have to have a lot in your tool belt and try different things.” Use mirroring to open up a conversation and try to engage the child in a reciprocal exchange. Dr. Samelsen explains how mirroring is used to engage a child who might use repetitive movements or sounds. Imitation is used to gain the individual’s attention and encourage self-expression. The gains may be very small, but the goal is any improvement in engagement.

Educate and prepare your child for the best possible future. With access to education and support from state agencies, such as Regional Center and the Department of Rehabilitation in California, many adults with ID can be productively employed, have social relationships, find partners, and have interdependent, self-determined, enviable lives. For more guidance, read our article The Transition to Adulthood.

Support their mental health. According to a report by The Arc, up to 40% of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities experience co-occurring mental illness, such as depression and anxiety. Some things that can help include emotional and peer-led support groups, community activities, and social supports. Find more information in our series of articles on mental health and kids with disabilities.

Collaborate with their school team. Work with their IEP team to find the classroom accommodations that work best for their unique needs. You can also find out what they are learning at school, such as specific functional skills like counting money, and try to incorporate them at home to better support them.

Determine the best educational setting. The best setting for your child at school will depend on many things, including goals, instruction, related services, and any supports that the student needs to make meaningful progress academically and socially. This can include the general education classroom (the least restrictive environment) or alternative options such as a Special Day Class in California. While a number of research studies, such as a recent multistate research project published in 2022, show that students with ID have better outcomes in inclusive settings, it is ultimately up to you, together with your child’s IEP team, to determine what is the best fit for them. As it stands now, nationwide, only 20% of students with ID spend 80% of the day in a regular general education classroom.

Find support. Whether you need practical advice or emotional support, it can help to connect with and talk to other parents whose children have an intellectual disability. You can join the Undivided Facebook group for parents and find a local group near you.

Join for free

Save your favorite resources and access a custom Roadmap.

Get StartedAuthor