Autism in Girls

Far more boys than girls are diagnosed with autism: according to the latest numbers from the Centers for Disease Control, boys outnumber girls nearly four to one with respect to autism diagnoses. But does that mean there are actually more boys than girls with autism? Research tells us another story: many girls with autism are often misunderstood, misdiagnosed, or undiagnosed. Articles about the “lost girls” and “invisible girls” illustrate why girls with autism, especially those with lower support needs, are so often overlooked in autism research and diagnosis, and thus miss out on the crucial support they need. Girls often receive a diagnosis later in life, and on average they are diagnosed nearly 1.5 years later than boys. While boys are more likely than girls to be diagnosed with autism, children diagnosed with profound autism are more likely to be girls.

To explore more about autism in girls, including how it can manifest differently in girls than in boys, why a possible autism diagnosis might be overlooked in girls, what supports girls with autism need, and more, we sat down with Dr. Abha R. Gupta, MD, PhD, developmental-behavioral pediatrician and associate professor in the Departments of Pediatrics, Child Study Center, and Neuroscience at the Yale School of Medicine; Dr. Lauren Stutman, PsyD, licensed psychologist and founder of CARE-LA; Dr. Hitha Amin, MD, neurodevelopmental neurologist at Children’s Hospital Orange County; and Dr. Sarah Pelangka, special education advocate and owner of KnowIEPs.

Traits and features of girls with autism

Autism is a developmental disability characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction as well as restricted, repetitive behaviors and interests, according to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. However, the experiences and intensity of symptoms will vary for each child, which is why autism is considered to be a spectrum.

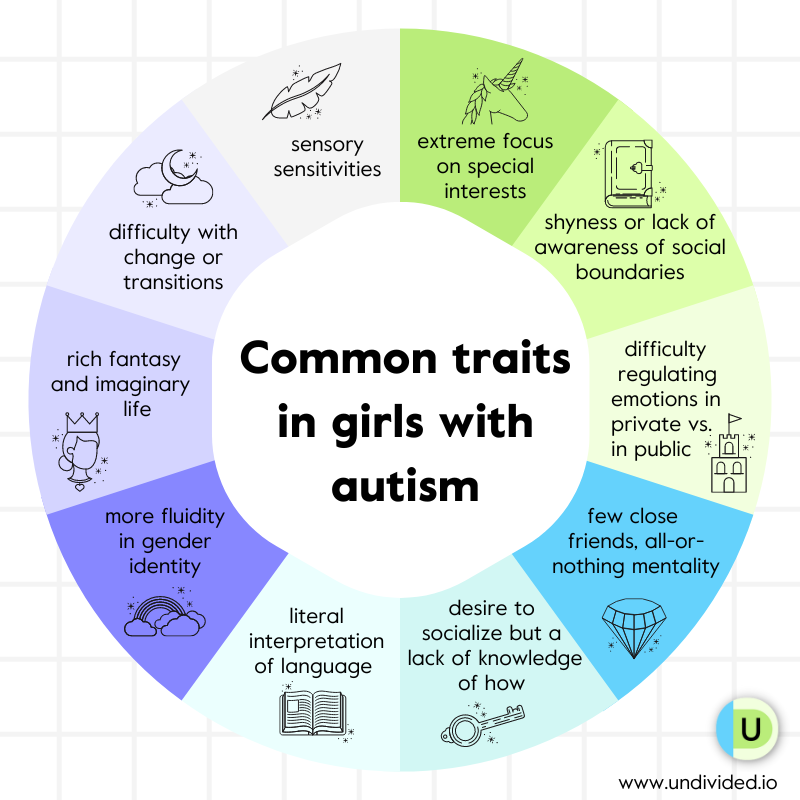

Here are some traits and features of girls with autism, including those that boys can have as well and some girl-specific traits:

- an extreme focus on special interests (for example, animals, psychology, fictional characters, movies, etc.)

- shyness or lack of awareness of social boundaries

- difficulty regulating emotions, sometimes displaying typical-seeming behavior in school and in public but with meltdowns or shutdowns occurring at home

- few close friends but with a view of friendship as all or nothing

- an extreme desire to socialize but a lack of knowledge of how to do so

- a literal interpretation of language

- more fluidity in gender identity

- a rich fantasy and imaginary life

- a desire for things to be certain or the same; difficulty with change or transitions (cognitive inflexibility)

- sensory sensitivities, especially around taste, smell, and touch

- repetitive play (as opposed to pretend play), such as sorting their dolls’ clothes or shoes by color

How is autism different in girls than in boys?

Boys and girls with autism share some common traits, but girls can sometimes present with a different profile of autism. “We see a lot of differences between boys and girls,” Dr. Stutman tells us, “but I believe people are starting to get on board with how to identify girls.” She explains that society genders girls, teaching them to be more considerate and caring of others, which isn’t equally true for boys. This might be why boys are referred for an autism diagnosis 10 times as often as girls. Girls are also more likely than boys to mask — meaning to camouflage the signs of their autism — which can make early identification of autism more difficult, with data estimating that 80% of girls with autism remain undiagnosed by the age of 18.

Dr. Abha Gupta, who is part of a research group studying girls with autism, explains the differences between girls and boys with autism:

Other ways girls and boys differ in their presentation of autism can include the following:

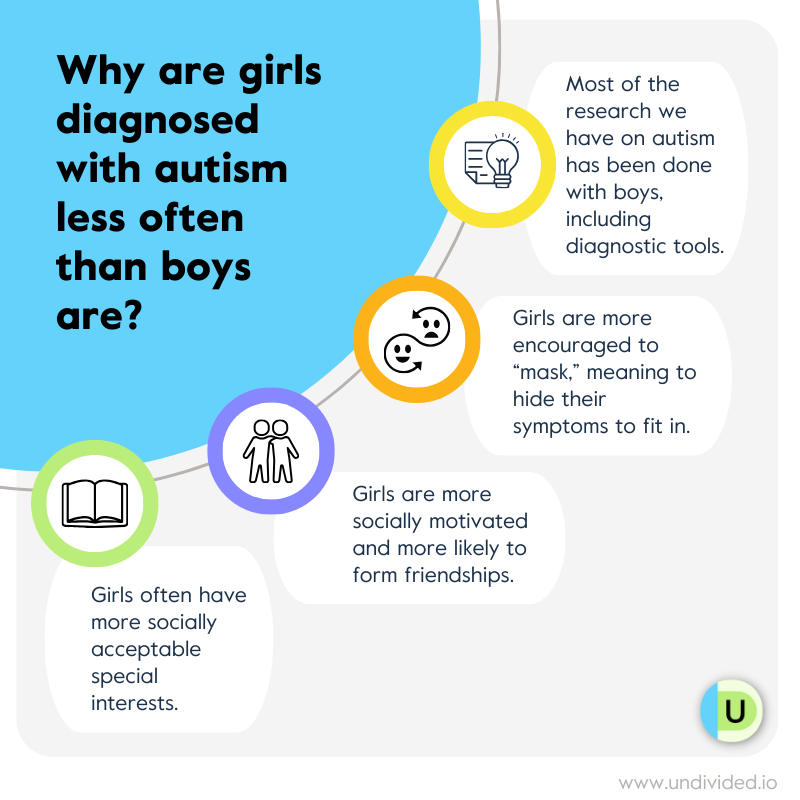

Girls with autism tend to be more socially motivated than boys (having the desire and intent to form friendships with others) — at a similar level to typical girls — but may find it harder to maintain long-term friendships or relationships. They’re also more likely than boys to mimic others in social situations and to want to fit in with other kids.

When it comes to restricted and repetitive behaviors and interests — which encompasses stereotyped motor movements, tics, and self-injurious behaviors as well as compulsive, ritualistic, and restricted behaviors and interests — girls with autism display less repetitive or restricted behavior than boys. However, it’s important to note that girls may just have different repetitive or restricted behavior than boys (which isn’t captured in diagnostic tools), and sometimes their repetitive or restricted behavior is just more socially accepted than that observed in boys.

Girls with autism tend to be more interested in things with relational purpose (e.g., animals, fictional characters, art, dolls) or random objects (e.g., stickers, stones, pens), and play obsessive and repetitive games. Boys’ interests tend to be focused on more mechanical topics such as vehicles, computers, video games, or physics. Girls’ interests are often seen as more age-appropriate when they’re younger and are less likely to be reported. However, unlike in typical girls, special interests of girls with autism are more pronounced and fixated, and they usually continue on into adolescence toward young adulthood.

Girls are more likely to have internalizing symptoms compared to boys. This refers to the inward expression of emotional difficulties (for example, anxiety, depression, self-harming, eating disorders, etc.). Boys, on the other hand, exhibit more externalizing symptoms, such as behavioral problems and inattention.

Girls have fewer linguistic difficulties than boys and are more likely to demonstrate “linguistic camouflage,” such as saying “um” more often in conversations, which signifies greater social communicative sophistication than what is often seen in boys with autism. Girls have also been found to produce more socially focused language — words that reference people, including family and friends — which may mask their social difficulties.

A study from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia showed significant differences in storytelling: despite similar severity in autism symptoms, girls with autism used more cognitive process words, like think and know, that show attention to other peoples’ internal states than boys with autism did. This indicates that prior research showing that autistic children use fewer cognitive process words may be true only for boys.

Girls also struggle more with executive functioning and daily living skills, including organizing information, planning and completing daily activities, accessing working short-term memory, exercising impulse control, and demonstrating cognitive flexibility.

✅ Parent tip: help girls find a balance between the same and the new. When it comes to interests and fixations, it’s important for parents to support and validate what brings their daughters joy while also helping them explore other things. For example, Dr. Stutman shares that if kids prefer to watch TV all day, it’s important to honor that it brings them joy, safety, and comfort, but it’s also important to engage them in other activities and plans so they’re not perseverating on one thing.

Are there differences in the early signs of autism?

The evidence for differences in early signs of autism between girls and boys of toddler to preschool ages is conflicting. The general consensus is that in early childhood, boys and girls with autism present about the same. In fact, a meta-analysis found that the gender difference in restricted and repetitive behaviors does not become apparent until six years of age. Dr. Gupta tells us that parents can look out for symptoms of autism in early childhood, even if they appear different from what you would see in a boy. For example, if a girl has an intensity about a specific preoccupation, parents can still be aware of that.

Co-occurring diagnoses

It’s very common for children diagnosed with autism to experience co-occurring medical or mental health challenges and conditions. In fact, girls with autism are more likely to have other conditions than both typically developing girls and boys with autism are. Dr. Stutman shares with us some common co-occuring conditions girls with autism can present with:

Anxiety disorders: Girls with autism were found to be 2.2 times more likely to have anxiety than boys with autism. (In the typically developing population, girls are only 1.4 times more likely to have anxiety than boys are.) Social anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder, and specific phobias are some examples of commonly observed anxiety disorders.

ADHD: Girls with autism may also exhibit symptoms of ADHD, such as difficulty with attention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity.

Mood disorders and depression: Girls are at an increased risk of experiencing depression due to the challenges they face in managing social interactions and coping with sensory sensitivities. They may also experience other mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder, characterized by significant mood swings between depressive and manic states.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder: OCD can co-occur with autism, leading to repetitive behaviors, intrusive thoughts, and ritualistic actions.

Sensory processing issues: Many girls with autism have sensory processing difficulties — even more so than boys with autism do — especially with taste, smell, and touch.

Epilepsy: Some girls with autism may also have epilepsy or other seizure disorders, which can further complicate their overall health.

Language difficulties: While communication challenges are common in autism, girls may present with special language disabilities that impact their ability to understand and use language effectively.

Eating disorders: There is also a possible connection between autism and eating disorders — 20%–30% of women in treatment for anorexia have diagnostic features that are characteristic of autism, such as cognitive inflexibility (for example, restricted and repetitive behavior and interests, insistence on sameness/ritualistic, and compulsive and self-injurious behavior). This could suggest that girls with autism who present with these behaviors are more vulnerable to developing eating disorders. Early diagnosis and support tailored to the whole child, as well as working with a provider who understands the overlap, can help with adapting interventions to the child’s specific needs. For example, some girls with autism may not benefit from group therapy, which is common in treating eating disorders, but they may like dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) — a form of therapy designed to help manage intense emotions — or occupational therapy.

Intellectual disability: Intellectual disability (ID) is also a major factor during diagnosis for girls with autism. A CDC study found that girls are more likely to be diagnosed with co-occurring autism and intellectual disability than boys are. Other studies have found that girls with both autism and ID are seen to be more impacted than boys with autism and ID. Certain biases and stereotypes around intelligence, language, and behavior in autism can also create an overestimation of ID in girls who have higher support needs or profound autism. Researchers have also suggested that girls are more likely to be diagnosed with autism if there is co-occurring ID, which could mean that girls with autism who do not have ID are being missed.

While this list is enough to alarm any parent, remember that your child won’t necessarily have one or all of these co-occurring conditions. It’s important, however, to be on the lookout for the signs and symptoms so as to provide them with services and resources as needed.

✅ Parent tip: girls with co-occurring conditions such as depression, OCD, or anorexia may need more specialists on their team, such as mental health therapists or psychologists. Ask your provider about the options available for your child. Dr. Stutman shares that for some children, therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help by addressing anxiety, depression, and other mental health concerns commonly seen in girls with autism. CBT can help girls identify and modify negative thought patterns, develop coping strategies, and improve emotional regulation.

Why are girls diagnosed less often than boys are?

Girls with autism may be harder to diagnose for many reasons, including stereotypes around what autism “should” look like (most diagnostic criteria are developed around boys); the relationship girls have with their autism and how they cope with, mask, and compensate for their symptoms; social and cultural factors; and even biology — something researchers call the female protective effect theory, which says that girls and women may be biologically shielded from autism.

In one study, researchers found that girls with an autism diagnosis have more difficulties in social communication than boys with the diagnosis, also suggesting that girls may be more likely to be diagnosed only if they have significant social challenges. Another study on sex differences in autism found that the traits required for an autism diagnosis tend to differ for girls and boys, resulting perhaps in the diagnosis bias. For example, girls are less likely than boys to be diagnosed with autism even when parents report high levels of repetitive and restricted behavior symptoms. However, the probability of diagnosis increased in girls when parents reported high levels of emotional and behavioral challenges.

✅ Parent tip: Dr. Gupta tells us that if parents suspect their child has autism, they should ask their primary care provider for a referral to a specialist who has expertise in evaluating children with developmental delays and autism, such as a developmental-behavioral pediatrician or a child psychiatrist or psychologist. Parents should be prepared to provide very detailed developmental history, a medical history, and a description of their child’s behavior in various settings, such as at home, in school, and in public.

Girls with autism don’t always fit the “model”

The current model we have of autism is a “male model” — developed based on years of research around boys. Dr. Gupta tells us, “Because boys are diagnosed more commonly, they're more easy to recruit for scientific studies. For a long time, studies would have a relative lack of girls as research participants, so we know less about the female profile. The lack of girls in research studies is being increasingly addressed, and people are trying to make up for that now.”

Dr. Gupta tells us that even some of the diagnostic instruments used in clinics were developed on research participants who were mostly boys. She adds that while gender-specific tools don’t exist, some research groups are trying to develop them, including the one she belongs to. She tells us that one of their goals is to develop self-reporting tools for symptoms of autism to capture girls and women who were misdiagnosed or diagnosed late, which would help them better understand what their profile is in an effort to find them earlier in the future.

Historically, girls are more likely to be diagnosed with autism when certain traits or behaviors are exaggerated or more closely aligned with the “male model” of autism. Some parents have even reported a need to exaggerate their daughter's traits of autism in order to obtain a diagnosis.

A CDC study found that girls were 1.25 times more likely than boys to be diagnosed with profound autism. They attributed this to the fact that girls with lower support needs or those who don’t fit the current model of autism are often missed or overlooked, which leads to a bias in the way autism is interpreted in girls.

Girls may mask

Often, girls with autism are able to blend in or hide in plain sight, a behavior that is called camouflaging or masking. Masking is a social coping strategy that involves hiding behaviors of autism in order to manage social situations and fit in with others; masking can include actions like suppressing stimming behaviors, such as flapping of hands. In addition to hiding behaviors of autism, girls who mask may also mimic facial expressions and gestures to display context-appropriate expressions and gestures, make intentional eye contact, and give scripted responses to questions.

Dr. Stutman tells us that society often encourages masking with girls more than with boys. It typically begins as girls grow up and start school, where they’re faced with social and cultural pressures, expectations, and gender rules and norms. Girls mask more often at school and in public where there is pressure to fit in; there is usually less camouflaging at home. Some reasons why a girl might mask include to avoid bullying or humiliation, to overcome challenges in making friends and maintaining friendships, and to camouflage immature interests or learning challenges.

Dr. Gupta tells us, “Because of expectations of cultural gender roles, girls try to mask their social challenges. While symptoms may seem less obvious, they may be exhausted internally trying to continually fit in and understand social situations. They may seem less impaired, but that doesn't mean they don't need support.”

Another form of camouflaging is called compensation, which occurs when a person uses alternative cognitive strategies to overcome challenges related to their autism. For example, girls with autism can compensate by intellectualizing social interactions that would be intuitive for others. They learn social rules intellectually, perhaps by observing and mimicking, rather than instinctively. This is one reason why health providers must be open-minded and creative when diagnosing girls.

Masking can result in challenges, including mental, physical, and emotional drain. Masking is characterized by constant monitoring of what are deemed to be socially acceptable behaviors, which can be quite draining for the individual. Dr. Stutman explains, “Girls who effectively mask their autistic traits may appear more socially adept than they actually are, which can result in a discrepancy between their apparent social competence and their internal struggles, leading to difficulties in forming genuine connections and relationships. They may experience a sense of isolation and struggle to maintain friendships.” Some girls may even feel they are betraying themselves, and others, by not being their true selves.

✅ Parent tip: it’s important for parents to adjust their expectations. If your child is masking all day long, she’ll probably feel exhausted when she gets home. Parents sometimes hold kids with autism to the standards of a neurotypical child, Dr. Stutman explains. Parents may need to adjust their expectations to care for their kids’ well-being — for example, by scheduling fewer after-school activities and more downtime.

What are some common challenges girls with autism face?

Adolescence

Adolescence is tough for everyone, but it can be extra challenging for girls with autism. As they enter their teenage years, girls with autism may have a more difficult time learning and keeping up with the elaborate and often “hidden” rules of friendships, relationships, flirting, and social hierarchies. This is also why adolescence can create more opportunities for diagnosis. Some of the common challenges girls with autism face in school include internalizing and hiding anxiety, navigating peer relationships, experiencing bullying and exclusion, engaging in teamwork, completing tasks and experiencing executive functioning challenges, and understanding class rules.

Dr. Stutman explains how much harder it is for girls as they get older because the necessary social skills become increasingly subtle. The challenges can be compounded by social media, where a person who struggles with social cues may miss the subtleties in online communication and then face social exclusion or bullying because of any missteps they make. Dr. Stutman adds that clear communication with the school is imperative when any kind of bullying is occuring. Parents (and the girls themselves) can advocate at school and speak up if bullying is happening. For girls with autism who struggle with identifying bullying or advocating for themselves, parents can also teach them how to do so, as well as how to approach a trusted adult if it is occuring. (See our article on bullying for much more information on this topic.)

Girls may have a “protective factor,” especially in early childhood, due to the brain systems involved in social behavior that develop more quickly in girls, but as they enter adolescence and social relationships become more complex, girls with autism may begin to stand out more and possibly face bullying if they can’t keep up the systems of masking they relied on earlier. Girls are much more likely to feel isolated and develop anxiety and depression during this age because of this prominent shift. It’s important to note that if they’re also separated into special education classes for autism, it’s likely that they’re in classes mostly with boys who have autism, leaving them potentially unable to easily access friendships with girls.

✅ Parent tip: promote inclusive and accepting environments. Dr. Stutman explains that parents can help their kids by encouraging positive social connections (within and outside the autism community) and facilitating opportunities for social interactions, friendships, and participation in activities that align with their interests and strengths. Parents can also be proactive and work with the school and the child to ensure no bullying takes place.

Socialization

While every child enjoys playing in their own way, boys with autism more commonly prefer to play alone on the playground, while girls with autism typically are more involved in group play. But there is a caveat — although physically present with other girls, girls with autism are often less involved than typically developing girls in social chatting during play. “You can see how it would be easy to miss the subtle way they were not truly connecting and forming relationships with their peers,” according to Erica Rouch, a researcher and psychologist with the University of Virginia’s Supporting Transformative Autism Research initiative. “And of course, these girls are also missing a foundational experience that would help prepare them for the complex social relationships of adolescence.”

While boys with autism sometimes isolate themselves or socialize loosely with other boys while focused on shared interests like video games, girls with autism tend to place equally high importance as typical girls do on their friendships, but they may need need extra support to help them develop their relationships, especially when it comes to making and keeping friends, resolving conflicts, and dealing with rejection.

While typical girls may have a large group of friends, girls with autism often prefer having one or two close friends, which means that conflict within their relationships can feel even more devastating. As one study shows, girls with autism are more likely to be victims of conflict within friendships (for example, gossip, silent treatment, exclusion, etc.) and less able to understand the social rules or expectations. Some girls with autism who face conflict in a friendship may need advice about the two-way street of friendship and how to work out a compromise to resolve conflict.

✅ Parent tip: Teaching girls social and safety skills is very important, Dr. Stutman explains. Explore supports like speech therapy, social skills training, and structured play, and teach how to recognize and respond to social cues, set boundaries, and communicate needs effectively. If parents want to support their kids as they navigate friendship and socialization, they can look to building resilience, such as promoting a positive self-image and emphasizing their strengths. Dr. Stutman adds that parents can help kids develop coping strategies for managing stress and adversity, engage them in activities that build confidence and provide opportunities for success, and teach them self-advocacy skills using visual aids, Social Stories, or assistive technologies (e.g., Proloquo on an iPad). Dr. Pelangka adds that we — as parents, teachers, schools, etc. — must also simultaneously educate their neurotypical peers on how to support social interactions.

Reading about other girls’ experience with autism can help girls not feel so alone. Here are a few books to check out:

- The Spectrum Girl’s Survival Guide – How to grow up Awesome and Autistic by Siena Castellon

- The Autism-Friendly Guide to Periods by Robyn Steward

- The Girl Who Thought In Pictures: The Story of Dr. Temple Grandin by Julia Finley Mosca and Daniel Rieley

- Can You See Me? by Libby Scott and Rebecca Westcott

- Good Different by Meg Eden Kuyatt

- Camouflage: The Hidden Lives of Autistic Women by Sarah Bargiela and Sophie Standing

- For parents: What Every Autistic Girl Wishes Her Parents Knew by Inc. Autism Women's Network

Find more great books on A Mighty Girl!

✅ Parent tip: role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) can help kids with autism develop social skills. It can also function like group therapy; there are many D&D groups for teen girls who have experienced trauma. Here are 15 ways D&D can help girls with autism!

Puberty and personal safety

All the guidebooks in the world can’t always help our children navigate interpersonal relationships or deal with other major life moments, such as puberty, dating, sexuality, and personal safety. Children with autism often experience asynchronous development, in which they may be way ahead of their age in one area but behind in another. Girls with autism are no exception, and sometimes an area of delay is maturity, which can result in unsafe situations that can open up doors to being taken advantage of by bullies, sexual predators, friends, or romantic interests.

Neurodivergent girls often need ongoing support to maintain safety. Teaching them about boundaries and personal safety is very important, especially for older girls who may not be aware that they are being manipulated. For more information on this, author and certified sex educator Terri Couwenhoven, MS, CSE specializes in personal safety and sexuality for people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities and their families. Find more information on her books and talks here!

✅ Parent tip: parents can teach their girls personal safety rules and boundaries, such as what is private vs. public and appropriate vs. inappropriate, or even a watch set to vibrate at fixed intervals to remind girls to go to the bathroom to promote menstrual and body hygiene. Parents can also speak to their child’s school prior to the onset of puberty and work collaboratively to provide resources for use at school and at home.

Adolescence and puberty may be more difficult for girls with autism who also have ID or who don't have much spoken language. Girls may need extra help with daily living tasks (for example, using feminine hygiene products, wearing a bra, applying deodorant or makeup, washing their hair, etc.). While some girls may be confident in their ability to manage their periods, for example, others may need more support. Body autonomy and hygiene are important for developing confidence and independence, so parents and other caregivers can work with girls with autism to develop the skills needed to manage their own bodies. Studies show that the less reliant on others girls with autism and ID are, the less vulnerable they will be, which shows the importance of giving them the opportunity to learn to manage their own bodies.

✅ Parent tip: joining a group of like-minded girls can help girls with autism cope in a safe space with many of the challenges of socialization and puberty they face. Finding a local community or social group, or even a virtual group, can be a great option. Look for social and recreational programs that focus on communication and social differences through fun group activities (such as art classes, swimming, horseback riding, and movie nights) as well as relationship building, self-care skills (for example, personal hygiene and positive emotional and behavioral practices), and self-determination and individual autonomy. For example, PEERS at UCLA offers social skills groups for teens and their parents, and even offers a virtual program. Read more about talking to kids about puberty and periods in our article Preparing for Puberty.

For Undivided member families, our research team can work with you to find a local community or social group that matches your priorities and supports your girls! Don’t hesitate to reach out!

IEP goals

Poor IEP goals is another challenge that girls with autism can face. For many of them, IEP goals actually promote masking their traits in an attempt to “normalize” their behavior (for example, goals for more eye contact, tone policing for appropriate responses, constantly initiating conversations, etc.). Certain goals can set up girls for manipulation, exploitation, and bullying. Many of these goals have the word “appropriate” in them — as in “appropriately respond” or “appropriately acknowledge” — and may be expected even when a girl is being teased or bullied. In addition, there is often more of a concern for girls to “fit in” and seem “nice” than there is for boys of the same age.

Dr. Stutman explains that this may happen if professionals are not well-versed in autism. Parents can reach out to the school and advocate for staff training on the latest research in autism, including the best methods for supporting kids with autism.

Dr. Pelangka explains that goals, whether clinic-based, home-based, or in the IEP, shouldn’t be aimed at trying to change the person but to support them in what they actually desire for themselves. For example, it’s not necessary to establish goals for more eye contact. It can be overstimulating for their brains, it depends on the culture, and individuals can show that they are engaged in other ways (e.g., remaining in the area, facing the direction of a communicative partner, responding with related responses, etc.). “We should aim to give them the tools to have meaningful and positive social experiences,” Dr. Pelangka says.

“Some may argue that ABA and social skills training try to rid individuals of their autism — of who they are — but I believe people with autism want to be social. We know, through research, that individuals on the spectrum are at much higher risk for depression, and their suicidal rates are also much higher (often due to social isolation and not wanting to be different). We need to do better at providing individuals with autism the tools to have positive social experiences, and equally as important is the need to simultaneously educate neurotypical peers on how to support said social interactions: how to understand autism and be good friends.”

How can goals support a girl with autism? Dr. Pelangka tells us, “People with autism often want the same things we do; they just need support in getting there.” While goals should be tailored to the individual, she explains that some girls, for example, may need goals to support conversation skills (such as not walking away or how to handle gossip) because many girls are more verbal than boys by nature. She also emphasizes goals around periods and feminine hygiene, sex education, female friendships, and romantic relationships.

Here are a few more examples of goal areas:

- building self-esteem, self-confidence, and self-trust

- promoting autonomy

- validating their unique style of communication

- teaching self-advocacy skills and that they have control over their own bodies

- building relationships

- teaching them how to say no and have social, physical, and emotional boundaries

- exploring and developing coping skills for anxiety, depression, and exhaustion

- managing negative thinking

- learning how to complete daily tasks, self-presentation, and hygiene

enhancing social-communication skills and promoting positive social-emotional health

✅ Parent tip: providing access to mental health resources, such as psychotherapy, can help adolescent girls with autism who may be developing anxiety or depression. You can explore CBT, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), or other types of treatment your child’s therapist may use; for example, art, music, and/or dance can help your child express and cope with their emotions or mindfulness, and breathing exercises or meditation can help reduce stress and anxiety.

Diagnosing autism in girls

✅ Parent tip: talk to girls about their diagnosis. Dr. Stutman tells us that some kids can fixate on their autism diagnosis and see themselves only through that lens, especially if they have a co-occurring OCD diagnosis. Talking to your kids about their diagnosis can include one very important conversation: that they are so much greater than one diagnosis.

To learn more about the process of diagnosing autism, check out our article Diagnosing Autism.

Flying under the radar at school

Many girls with autism benefit from individualized services and supports provided through an Individualized Education Program, or IEP. But diagnosing autism as a medical diagnosis is distinct from qualifying for an IEP through assessment for autism at school. According to the IDEA’s definition, autism is “a developmental disability significantly affecting verbal and nonverbal communication and social interaction, generally evident before age three, that adversely affects a child’s educational performance.” It’s possible for a girl to have a medical diagnosis of autism but not qualify for special education services under autism at school.

If the school finds a student eligible for services under autism but the student has not yet been evaluated in a medical setting, families should have their child assessed by a specialist such as a developmental pediatrician, child psychologist, pediatric neuropsychologist, or pediatric neurologist. To learn more about how a child with autism is assessed for special education services, read our article Getting a Child with Autism the School Supports They Need.

However, girls may fly under the radar at school, especially if gendered stereotypes affect the way their behavior is interpreted. For example, boys’ symptoms may come to a teacher’s attention sooner and be seen as more intrusive, while girls may be seen as just shy, anxious, or well-behaved. In one study, teachers reported no concerns with conversational skills in half the girls with autism (compared to the findings of 17% of clinicians). “As a result of masking while at school, we tend to see more problems at home, and this is where the disconnect lies,” Dr. Pelangka shares. “Parents get the brunt of the breakdown because their child breaks down at home, while teachers say they don’t see any of that in the classroom. It’s exhausting, and all children are more comfortable at home, where they can release and be themselves.”

✅ Parent tip: communicate with your child’s teacher and IEP team often! Document what you see at home and make sure you share them with the team at parent-teacher and IEP meetings. You’re your child’s biggest advocate!

Misdiagnosis and late diagnosis

It’s not uncommon for girls with autism to be misdiagnosed, sometimes repeatedly. Overall, girls are more likely to manage their behavior in public and less likely to have public meltdowns, make socially inappropriate comments, or speak too loudly. Girls are better able to mask their autistic behaviors at school, and many parents report that their kids often hold it together at school but come home and release all the pressure of masking all day — called the “4 o’clock explosion.”

Dr. Pelangka tells us that one of the most problematic issues she sees is the assumption that because a girl is social, they don’t have autism (which can also occur with boys). Girls with autism may be more social than boys, but their social skills are still hindered, just not in the stereotypical way, she explains. For example, they may be better at imitating what they see in their peers without knowing when to turn it on/off; they may overshare or not know when to stop talking about certain subjects with friends; or they may say things at inappropriate times (for example, using current slang but not when expected).

Dr. Stutman tells us that some girls may get diagnosed with borderline personality disorder instead of autism, which highlights the importance of ruling out the possibility of masking during diagnosis: “Sometimes, what is seen as a difficult personality is actually a manifestation of undiagnosed autism.”

She adds that girls with autism can also be misdiagnosed with ADHD, as both autism and ADHD can involve difficulties with attention, focus, and impulse control. Social communication disorder — difficulty using language to interact with other people — also shares similarities with autism, such as difficulties in social interaction, but those with SCD do not exhibit the repetitive behaviors and restricted interests that are typical in individuals with autism. Symptoms of anxiety may be the primary focus of concern, leading to misdiagnosis of an anxiety disorder.

Can age affect diagnosis?

For girls, the likelihood of receiving a misdiagnosis or a co-occurring diagnosis is also linked to the age at which they receive their autism diagnosis. Early screening is key because over time girls learn to use social camouflaging skills — it’s unlikely that toddler girls with autism would have the necessary social skills to camouflage socially. When screened earlier, both boys and girls with autism are identified early on. Girls identified early on (before the age of two) typically demonstrate greater developmental, behavioral, or intellectual delay, or behavior that is more “externalizing” or more difficult to manage.

Girls who receive a late childhood diagnosis of autism (at age 11–15 years), however, are diagnosed with psychotic disorders, OCD, eating disorders, and anxiety more frequently than those who are diagnosed with autism in early or mid-childhood. In contrast, ID is diagnosed in around 40% of those with an early autism diagnosis and in only around 10% of those with a late autism diagnosis.

Girls are less likely to be diagnosed with autism on their first evaluation by a health provider, despite the number of visits made, the age at which parents first expressed concern, or how long the clinical assessments were. In one girl’s case, it took 10 years, 14 psychiatrists, 17 medications, and nine diagnoses before someone understood that she had autism. Throughout those years, she was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and many others. If a therapist or provider isn’t really digging deep, they can miss the manifestations of autism.

The cost of a missed diagnosis

Girls with undiagnosed autism may float through life wondering why they feel different or as if something is innately “wrong” with them. They miss early supports for skill building, especially social skills and support for learning in school. Being misdiagnosed means many girls don’t receive early intervention for autism, and even when they do, the standard interventions may not be appropriate or may not meet their unique needs.

But things are changing. For example, the latest DSM-5 criteria for a diagnosis of autism also includes this specifier, which may help girls with autism: “Symptoms must be present in the early developmental period (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities, or may be masked by learned strategies in later life).” This one line can help older girls who may be told, “If you had autism, you would have been diagnosed by now.” It also identifies how masking can delay or hinder a diagnosis.

What to do if you feel your child is being undiagnosed or misdiagnosed

If you feel your child’s autism diagnosis is being missed or misdiagnosed, you can always seek a second opinion or have your child re-evaluated after a few months. You can even find a provider who has experience specifically working with girls with autism. “It is okay to get a second opinion,” says Dr. Amin. “There's nothing wrong with saying, ‘We're not quite sure how accurate the diagnosis is in this case.’” And your input can help prevent a missed diagnosis because you may notice signs of autism within your child’s routine and daily behavior that other people in your child’s life (such as teachers) may miss.

Make sure you voice your concerns at the start of your visit with your child’s provider, and be ready to share what you’ve observed in confident, succinct sentences. The Connecticut Health Foundation has a great guide written by a developmental-behavioral pediatrician on how to talk to your child’s doctor about your concerns.

What should you do if your child is being overlooked at school, or if you’re told she doesn’t have autism because of x, y, or z? As a parent, you can request an assessment for an IEP at any time. If you believe that the school psychologist assigned to your child’s case is not qualified to assess students with autism, you can request an alternate assessor who is experienced in supporting students with autism.

If you disagree with the district’s assessment results because you believe their assessment was not thorough enough, or if the school conducts an assessment and the psychologist tells you that your child isn't eligible for special education services under IDEA, you have the right to an independent educational evaluation, or IEE. An independent assessment is conducted by a qualified professional who is not employed by the school district. The first step is to submit a written letter to the district stating that you disagree with the district’s assessment of your child and are seeking an independent assessment.

Dr. Pelangka tells parents to also look for an ADOS (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule) as part of their school evaluation, in addition to the questionnaires. If this is missing and parents are in disagreement, request the addition of the ADOS along with the IEE. If you do not get a satisfactory response, you can consult with an attorney who has experience in special education issues.

✅ Parent tip: don’t take no for an answer. It can take a long time to get a diagnosis. Dr. Stutman reminds us that it’s important to find a trusted provider who is knowledgeable about autism and has a very comprehensive history with your child. “I've worked with kids who were misdiagnosed for years before a neuropsychologist finally saw it,” she tells us. She adds that parents are the experts on their children. If you feel that your child is showing signs of autism, it’s important to work with a provider that you trust will support you.

How can interventions be tailored to girls?

Dr. Gupta tells us that every child with autism is unique in their clinical presentation and that treatment should be specific to their needs. Social skills training, behavioral therapy, speech therapy, AAC devices, and occupational therapy are a few of the supports that girls with autism can benefit from. While behavioral therapy is tailored to the individual, acknowledging the way autism manifests in girls can help these interventions address girls’ needs and promote safety, independence, and well-being. Read more about these in our article Autism Therapies and Specialists.

Dr. Stutman shares with us more types of supports for girls with autism (including undiagnosed autism) and their families looking for support.

How parents can support girls with autism

Girls with autism are a vulnerable population, but things are slowly changing. With more awareness, more studies, and more people speaking up, girls are less likely to be left behind.

✅ Parent tip: talk about everything. Get tips and strategies for supporting girls with autism with bullying, class rules, completing tasks and executive functioning, internalizing and hidden anxiety, friendship, and teamwork in the guide Spotlight on Girls with Autism.

Author